Current Events in the STEM Classroom: Mars Curiosity

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.This summer was quite literally a windfall for any teacher involved in educating students about STEM ideas. In one summer we were treated to the physics-laden Olympics, the engineering marvel of NASA's Mars Curiosity, and the statistically significant fingerprint of the Higgs Boson. It's little wonder why so many sources extol teaching STEM using current events in an attempt to generate relevancy in the classroom.

The trick is not in finding relevant happenings; it is in finding ways to present core standards embodied by these stories without coming across as contrived. I want my students to look at something real and respond with real questions. All teachers want this, but how can we take out an insurance policy against lessons that smack of "schoolness" instead of realness?

Students and Space

This process is not as magical as one may think, it usually just starts with a little confidence, some trust in your students, and a question:

"Hey, did you guys hear about the new NASA Mars robot?"

I have to trust that my students will ask questions that they actually care about. This can be used a barometer for the health of a classroom; when asked, do students take the opportunity to dig into things they actually care about, or do they try to ask the simplest question in order to "get done" with the subject?

My students asked the following:

- How much do you have to "lead" Mars (like in trap shooting) to hit it with the rover?

- Why aren’t we sending people to Mars?

- Why does it cost so much? (Compared to the Olympics, this is a fun question.)

- How much gas does it take to get to Mars?

Demanding Audience

Students grouped themselves by interest and began working. This is where the work on my part comes in: I need to help students identify an audience for their work. This might seem obvious (e.g. me, the teacher), but it's not. Basic human psychology demands that, because we're social creatures, our work should have as wide an audience as possible. Audiences motivate us to do work knowing that others might benefit from it, or provide feedback on it. I can't believe how much this change in focus has modified my classroom. This kind of feedback has a greater impact than any points total, and getting that feedback from outside the classroom is like a penicillin-dipped silver stake driven into the heart of boredom.

Each group decided on a different audience. Some thought they'd like to teach younger students. Some thought they'd like to like to contact NASA with their ideas. Some got a few local engineers to help them in finding data. To me, it doesn't matter. Any external authentic audience is integral to getting any learning done in my classroom.

Oh, Right, Grading

Organizing this kind of learning can be a nightmare for assessment. How can I grade the work of students who are handling a physics-centered question like trying to hit Mars from 54 million kilometers, versus students who are attempting to justify the $2.5B spent to get something the size of a VW Bug onto a barren, dusty desert?

The answer lies in how you use grades and scores. I'm a fan of throwing all the big ideas in my grade book as assignments. As students work through the semester on projects like this, I can get a good idea of how much they're learning, what direct instruction is needed (individual, small group, large group), and what concepts are solidified by what tasks. I let the scores on these big ideas (standards, learning targets, whatever) fluctuate up and down based on how the students are doing, so they can get an idea of what growth really looks like and, for some "smart" kids, what retention actually takes.

Engage

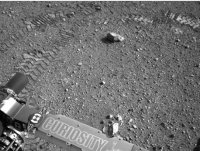

NASA's Mars Curiosity and its accompanying Mars Science Laboratory represent the ultimate in STEM. NASA is an amalgam of all things that make science education awesome, and funding NASA is something voters must take seriously. Using the Mars Rover to teach physics, algebra, engineering principles and programming skills not only benefits the students, but it sends the tacit message that exploration is of value, no matter how ineffable that value may be.

I have to admit, I refer to my classroom as "The Nerdery" and that a lot of my motivation for teaching STEM is driven by my love of the Star Trek ethos. Gene Roddenberry's vision of the future is appealing even to the non-geek: no money, no energy woes, altruism as a central value, and really awesome adventures in space. If I can inspire my students to work towards that kind of future, I can deal with the primary-colored uniforms.

Our students will go to Mars. Our students will live on the Moon. I suppose that by using Mars Curiosity, or Voyager I and II, or the Olympics, or what have you, it's just my way of making sure that it will be my students who end up there.

Find Out More

Let the Jet Propulsion Lab plan your lessons for you. Ask students what they think about Curiosity's tweets: @MarsCuriosity.