The Story of Claudette Colvin: Students as Historians

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Thinking back on my own personal history as a student, I have remarkably few memories of impactful learning happening inside a classroom. I remember social situations (both good and bad), I remember moments of personal connection with teachers, and I poignantly remember the small number of real-world, hands-on experiences facilitated by teachers.

Deep, impactful learning is learning by doing, learning by experiencing, and learning by discovering. When learning is built around these beliefs, classes can be structured so that creation and discovery happen both inside and outside of the classroom walls. With this in mind, I structure the study of history around the concept of students working as historians. Instead of restricting them to memorizing dates and events, I want young people to understand that history and the past are contested and contestable. When doing the work of historians, instead of merely learning about history, students actively immerse themselves in gathering information, interpreting sources, and developing original ideas.

A Model Text

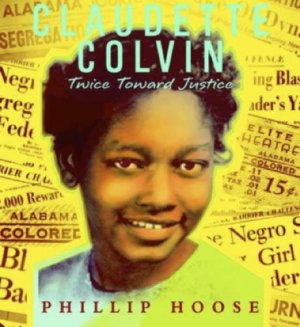

In every country, there are certain heroic figures and events that are widely accepted as parts of national ideology. In the United States, Rosa Parks is rightly celebrated for her role in the Civil Rights Movement and the actions she took that sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Most Americans don’t know that almost a year before Ms. Parks, a different young woman made the same choice on a segregated bus.

This past year, when my daughter and I discovered the book Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice in the library, it was immediately clear to me that we had encountered a story that provides rich material for learners to unpack about historical narrative, interpretation of sources, and national memory. The inside cover of the book sets the stage for the story within:

Phillip Hoose's book is an amazing combination of narrative, photos, interviews, and primary source documents. Reading the book provides an accessible, first-hand account of the product and process of someone doing history. It's a fascinating read and makes the process of historical discovery and the concept of historical narrative accessible to students.

A Classroom Example

Access to technology makes it possible for students to discover sources and present analysis in many innovative ways. After reading Hoose's book over the summer, while planning my own courses, I realized that Alexis de Tocqueville's famous book Democracy in America, published over 170 years ago, can still be used as a model text for a modern-day inquiry into the status of democracy in America.

In my American Government class, we began our unit by reading excerpts from de Tocqueville's work and discussing his findings, his process, and his product. I then introduced the project and the idea of doing the work of historians and producing work that combined multimedia with text. I shared different resources, and together we brainstormed questions for investigation of the chapters. Over the course of two months, students researched, did fieldwork, wrote, produced media, and consulted with me as they did history while playing the role of modern-day de Tocquevilles. At the end of the process, students excitedly chose modern-day de Tocqueville names for themselves, and we published their work. You can view all of the student projects from the unit on this site and read an article about the process by clicking here.

The work of historians is complex, controversial, and forces us to more deeply understand and examine our own realities. School should give students opportunities to learn in ways that challenge them to investigate meaningful issues, make their own discoveries, and produce work that matters in the world.