5 Ways to Unleash Student Creativity and Reduce Fear of Failure

Fear stifles creativity. By making space for the exchange of high-quality, low-stakes feedback, you can encourage the right kind of risk-taking.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.To stimulate creativity and risk-taking in the classroom you have to get students comfortable with an emotion that can cripple anyone: fear. Speaking to the Usable Knowledge blog, Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Karen Brennan says fear around creative work in the classroom—in any subject area—often shows up during the feedback process, when students worry about public exposure of their mistakes.

To loosen things up, Brennan says teachers can focus on creating low-stakes opportunities grounded in strategies that elicit quality peer feedback. These opportunities should be combined with clear principles and standards so that students understand what quality feedback—and true creativity—looks like: not settling for the first idea, for example, and embracing trial and error and the iterative process of drafting, revising, and revising again.

“It’s incredibly exciting to have your work seen by others, to have others respond to it,” Brennan said. “We don’t necessarily make as much space as we might in the classroom for that.”

A big part of the work also involves creating a classroom environment where students feel safe sharing and receiving feedback to begin with. For educators like Jamie Kobs, a veteran high school English teacher in Wisconsin, that means ceding some control over the learning process to her students, and encouraging them to see each other as sounding boards for their classroom work. “Having more frequent interactions among students builds rapport and trust and disrupts the idea that I’m the only expert in the room,” Kobs said.

As the top-down dynamics of a traditional classroom begin to shift—and cycles of peer feedback and revision become more familiar—students will feel more confident giving and receiving feedback and taking risks in their own creative work—whether that is a podcast, a piece of fiction, a work of art, or even a science project. As educator John McCarthy put it, creativity is a “fluid and flexible process,” and students need to get used to its messiness.

So how does this look in the classroom? Here are some strategies to jump-start honest and constructive peer feedback among students.

Use Simple Rubrics to Practice Feedback and Revision

To make feedback less daunting, limit the amount each student gets to just three or four of their classmates. Use the “red, yellow, green” strategy and ask each classmate to tell the student something they’d change about their creative work, something they wondered about, and something they liked.

Or you can try sentence starters to keep student feedback targeted and productive, and kickstart conversations for students who might normally be reluctant to speak up. Some possible sentence starters include “I like the way you… because…”—which steers students away from generalities and towards specific strengths—and “Maybe you can try…” or “Something you could do next…”, both of which evoke areas for possible improvement.

Once a student receives peer feedback, they should then have the freedom to choose what changes they will make to their work, according to Brennan. “Part of being a creative agent in the world is making sense of the feedback you get—listening to other people’s opinions, making sense of those, taking what is going to be helpful for you, and put aside that which is not helpful,” she told Usable Knowledge.

“In those moments, kids are making sense of the world and advancing their learning and thinking.”

Take Gallery Walks

“Gallery walks get students up and out of their chairs and actively engaging with the content and each other,” writes educator Rebecca Alber. A gallery walk could involve work displayed on a screen, written or creative work hung up on the wall, or even a display of a physical project on a desk. It can also be adapted to remote-teaching via shared Google docs. Students can leave written or video feedback, or meet in small groups over Zoom.

Gallery walks allow students to peruse each other’s work and can be integrated with other strategies like sentence starters or “red, yellow, green” to ensure that students are delivering high-quality feedback during their strolls around the room (or virtual room).

However a teacher chooses to adapt this strategy, Alber writes that the activity works best when the teacher remains in the role of a facilitator or participant in the activity.

Actively Model Good (and Bad) Feedback

Mark Gardner, a high school English teacher in Washington, writes that every year he stands before young writers afraid of the peer review process. They fear looking dumb and lack the confidence to provide productive feedback—or simply believe peer feedback rarely goes beyond “basic conventions” such as “I liked this part” or “I didn’t get this.”

Gardner uses the acronym SPARK—Specific, Prescriptive, Actionable, Referenced, and Kind—to guide the feedback process. Integrating a concept like SPARK in your own classroom will involve modeling it for students and helping them decipher between useful feedback and statements that are unlikely to lead to improvement. Gardner’s process includes modeling feedback by focusing on one example piece of text, and then gently prodding students towards specificity and story arc.

According to Gardner, these exercises help his students go from focusing on things like small syntax issues in their peers’ writing, to giving feedback that consists of clear statements such is “This is confusing because” or “Explain a little more about why you chose this example” that tend to hone in on bigger issues related to idea development, clarity, and arrangement.

The benefits to good, productive feedback should be reciprocal: “In the end, good peer review should provide the writer with meaningful information for improvement, while developing the reviewer’s ability to analyze a text’s effectiveness,” Gardner writes.

Update Your Repertoire

Part of getting kids to be more creative is allowing them to produce work in formats that excite and inspire them.

To get her students outside of their comfort zone and combat the “incredible blandness” of their research papers, Jori Krudler, a high school English teacher, turned to podcasting. She created small groups who generated possible topics to cover and—when students realized they had latitude to choose their own area of focus, which would be reviewed by their peers—Krudler’s students became “deeply invested” in creating something interesting and meaningful, she said. “In the end they worked harder on the analysis and synthesis—and did far more thinking—than they would have done if I were the only audience.”

Educator David Seelow writes that comic books can also be used in classrooms across subject and grade levels to encourage creativity and get students working together in groups to share feedback. Dividing students into teams that come up with possible storylines, with the ultimate goal of developing a physical comic book, is a collaborative, problem-solving activity that gets students thinking critically about narrative, plot, and character development. It also pushes students to share ideas as they revise and make decisions about what words and pictures they will use for their final product.

Offer Students Choices

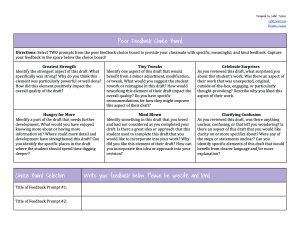

In her blog, Educator Dr. Catlin Tucker writes that a peer feedback “choice board” is an effective strategy that allows students to focus on a handful of prompts to guide feedback to peers.

The choice board is a simple diagram that includes six boxes with prompts that students can choose from to direct their feedback—students select two prompts only. Some prompts focus on the strengths of a piece of student work and ask questions like “What was specifically strong? Why do you think this element was particularly powerful or well done?” Other prompts focus on tweaks to improve a piece of student work, asking peers to think about “What would you suggest the student rework or reimagine in this draft?”

The process builds in agency while ensuring the feedback is “specific, meaningful, and kind,” Tucker writes. The choice board can also be adapted to various grade levels by adjusting the language included in each prompt.

Finally, you can add sentence starters to the rubric to give English language learners additional support. For example, under the box focusing on strengths, prompts can be substituted with fill-in-the-blank statements such as, “The strongest part of this draft was _____. I thought _____ was done well. I really liked _____.”