How Meditation Helps Me Teach a Tricky Physics Concept

Physics can feel inscrutable to students; this lesson helps them understand a graphing problem by analyzing their own breathing.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Consider this problem I assign every year in my algebra-based physics class:

A rocket is launched toward space with a steady speed of 6m/s. After 10 seconds, the engine providing that speed cuts off and the rocket free falls toward Earth. Draw a position versus time graph for the rocket’s trip from launch to return.

Students encounter graphs like this frequently, on motion detectors for free fall, in graphs of cars doing 0–60 tests, in theoretical problems about sprinters with resistance parachutes on, etc. But man, do they struggle with it. Rather than showing a straight line smoothly transitioning to a parabola, they draw the rocket suddenly zigzagging back toward the x-axis, not continuing to head upward while decreasing speed.

And they should struggle: These graphs are calculus in its simplest form. Students from previous years often come back to tell me how much they understand about physics now that they are taking calculus. It is easier to analyze a graph of position versus time once you understand and predict what a derivative is. A lesson I developed about meditation and breathing has helped make this concept clearer to students.

Mapping Yoga Breathing

Imagine you are doing box breathing in a yoga class. On your own count, you breathe in for a four count, hold your breath for a four count, breathe out for a four count, hold your breath for a four count. Suddenly, your instructor starts the count, and you realize that your four count is much shorter than theirs is. In that cycle of breathing, you start breathing in at a steady pace, but you find you must keep inhaling for a lot longer than you thought. As a result, you must slow down the rate at which you continue to breathe in.

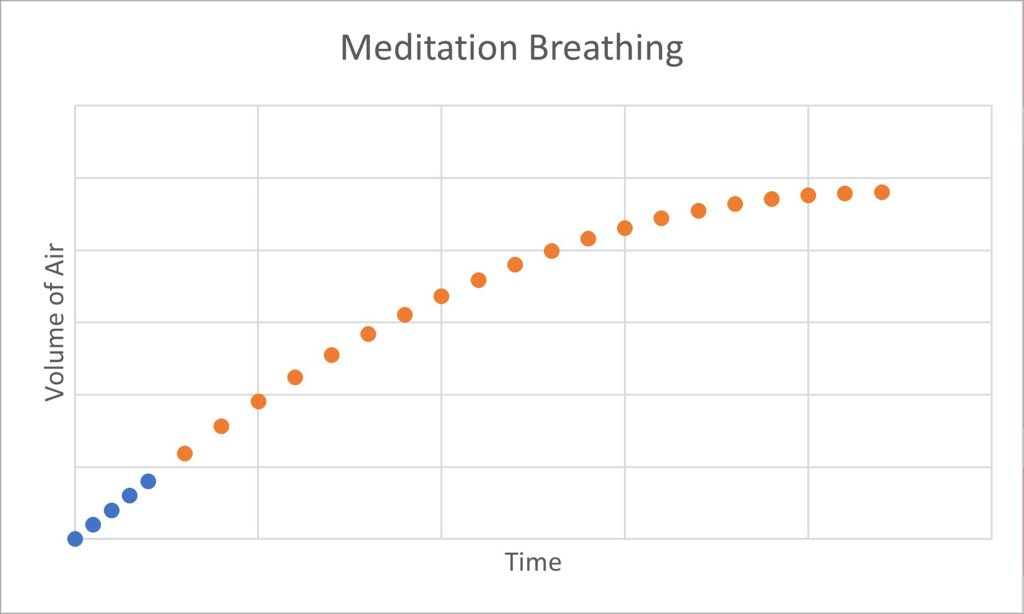

This happened to me in 2020 during a Zoom yoga class. When I experienced that change in inhalation pattern, I realized it was a great tool for helping my students in algebra-based physics understand graphs of position versus time for accelerated motion. When I change the breathing pattern, I experience an acceleration change. My speed changes from steady in to still breathing in, but at a slower rate as my lungs reach capacity. If I were to graph the volume of air versus time, it would be shaped like the image shown below. From breathing along, you feel the same shape in your body.

Modeling Kinematics through Meditation and Breathing

Inspired by my meditation experience, I decided to try to teach graphing using meditation and breathing to model kinematics. Over time, I’ve developed a fun lesson I look forward to teaching every year.

Meditation: First, I teach students about meditation and how people use it. Then, I lead students through a box breathing exercise. We watch a box breathing video that shows an animated circle with an object going up the sides at a specific pace. Then, I turn on some calming music and students box breathe on their own count. Finally, I interrupt them and introduce breathing on my count—much more slowly than most would normally breathe in, forcing them to make the same shape I experienced in my own yoga class.

Reflection: After leading them through the exercise, I ask students to reflect. First we just talk about the benefits of meditation. Students have observed that they feel more relaxed and that they observed new things about their body from breathing in at different rates. Then, we talk about the cycles I led them through. They’ve told me I punked them by adjusting the rates and that they noticed they breathed in at a different rate, filled their lungs more, and had to slow down their rate of breathing in.

Graphing: After this, I challenge them to make a graph of the volume of air in their lungs versus time. We label the “Total Capacity” of the lungs at the top of the y-axis and put the four-count on the x-axis. They show the air rushing in at first at a steady rate, then at a smaller rate until their lungs are at total capacity. They start making connections to their math classes, using terms like asymptotes and instantaneous rate of change.

Then, we graph the speed of the air on the y-axis versus the time on the x. This is where things start getting really challenging, since they must determine that the velocity can be negative (when air is leaving their lungs) and that the value of velocity is related to the steepness of the curve, which is changing.

Understanding the math: The mistake I usually observe with the rocket example is a V shape, showing the rocket stopping at maximum height, then regaining positive velocity. It is hard to picture the velocity having a negative value while the position has a positive value. But when students are picturing air changing from entering their lungs to leaving their lungs, the sign change is much more intuitive.

Again, for a calculus student, this graph should be easy to make. The velocity versus time is a graph of the derivative versus time graph. A parabola has a derivative that is a straight line, where the steeper the curve, the larger the value of the derivative, regardless of the location of the line. But without that math, this concept is a combination of a ton of skills. I’ve seen my students use their own breathing to think through the shapes of the lines. They can breathe in very shallowly to picture slow speed, or rapidly to picture quick speed. They can change their speed rapidly (because their instructions from the instructor make them do so), or they can change slowly to mimic the shape. I’ve often told my students to breathe in pattern as they work through graphing problems and see if they can feel their lungs tracing the shapes.

Benefits of cross-disciplinary lessons

This project gives me a way to teach social and emotional learning to students while still teaching cross-disciplinary content. We aren’t taking a random break to do meditation. We are meditating to learn physics and calculus. We talk about human anatomy and how your diaphragm drives breathing and what breathing from your belly versus your shoulders means. Often musicians in my class explain how these breathing patterns show up in their singing or instrument playing.

I also believe that it helps students understand that I am aware of student mental health. Physics can be challenging to students, and since I teach juniors in high school, many feel pressure to perform for college. Doing this exercise in September shows students that physics isn’t a roadblock to their future, and that I care for them and their well-being.

Every year, I’ve been aware of how hard students find physics. In my first year as a physics student, I didn’t like the topic at all. It made me doubt my intuition and feel frustrated, as if I just couldn’t possibly understand such an inscrutable topic. Finding lessons that show students that they are capable of this content, that it can be understood using your body and your senses, keeps me excited to teach and hopeful that my students won’t find it inscrutable just for the sake of inscrutability.