Supporting Multilingual Learners in Hybrid Classrooms

Hands-on learning strategies help English language learners participate in discussions—whether in-person or online.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.With virtual learning, and feeling like we are beginning teachers, we have the opportunity to reflect on how we can best support multilingual learners. Although teaching in an online environment is challenging, we can capitalize on shared experiences and interests to create opportunities for students to practice their language skills—all while learning science.

In Mary Modaff’s third-grade classroom, Amina, an immigrant from Bosnia, was demonstrating a push caused by air to her classmates. As she placed a paper airplane in front of a hair dryer, she told her classmates over video, “It goes there, and there, with one. Push.” Mary had the class watch the video again, this time pausing after Amina’s words. She asked, “Who can build on Amina’s claim? What is her evidence that there is one push?” Students talked about her clip, in the chat and out loud. Amina, often hesitant and shy in the whole group, was radiantly, keenly present.

Mary was creating virtual interaction between students by bringing together home and school experiences to develop language skills and science understanding. She aligned her teaching to the new vision of the 2020 English Language Development Standards from WIDA, already recommended for adoption in Wisconsin and poised for adoption in all 40 states in the WIDA Consortium. The standards focus on supporting language skills guided by the practice of the discipline. For example, instead of helping students use a conjunction such as and or but to join sentences together, these standards support language learning by encouraging students to learn how to argue with others using evidence and reasoning in science.

Conversation Maps Encourage Language Use About Science

Online learning opens up new communication possibilities for multiple language learners (MLLs), as well as shy students. Some of the apps, like Seesaw and Flipgrid, help students prepare their ideas ahead of time, enabling them to participate in meaningful talk about the topic.

In Melina Lozano’s second-grade class, students are encouraged to participate in each discussion in specific and unique ways. For some discussions, she relied exclusively on the chats, while in another discussion she had students message her privately for a prompt that related important questions and ideas in English and in Spanish. She said, “Here is a picture of the shrimp, clams, snails, and beetles that live in our wetland. Why do you think so many animals can live here?” She also led a discussion in which students sketched their ideas and held them up to their cameras to share with the rest of the class.

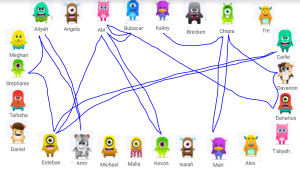

Third-grade teacher Stacey Hodkiewicz had the idea to use students’ avatars to illustrate co-construction of scientific claims. She put all the avatars in a circle on the screen. As one student responded to another, Stacey drew corresponding lines among avatars, tracing the students’ turns in talk, to show where the ideas had come from and where they went next.

In Melina’s and Stacey’s classes, project-based learning uses meaningful questions that support language practices that are often missing in science classrooms: the speaking, writing, and interaction that accompany the doing of science. They see that multilingual learners (as well as the students who speak English as their first language) benefit from interaction because students have negotiated meaning by exchanging feedback with each other.

Building with Materials at Home Taps Into Cultural and Linguistic Resources

Project-based learning, forging a bridge between science and community, can serve as the impetus for valuing the experiences of the students in their own homes. During the unit on designing and building toys, third graders interviewed their family members about the toys of their childhood. A Senegalese parent explained to his son how he had made boats out of Styrofoam.

One fifth-grade teacher, Alice Severson, had students learn about chemistry by mixing different ingredients found in their kitchen to develop a new taste. They investigated whether or not substances change color, texture, or state when mixed. While peers looked on, students located two foods in their homes, including macaroni, crackers, spicy rice, mango, and choclo, a Peruvian corn dish. Each student used AWW App, an online whiteboard app, to record predictions about what would happen when the foods were mixed. After combining ingredients (e.g., spicy rice and banana, macaroni and whipped cream) with cameras on, they shared their findings. Then the students observed their teacher mixing vinegar and baking soda. The class worked together on the shared model to show what might be happening, at the particle level, when substances are mixed.

As some students come back into the classroom, and some remain at home, all the students can work with physical objects—an effective hands-on strategy that helps build language skills and meaning-making as students investigate scientific ideas.

These examples show how the teachers can access students’ linguistic and cultural resources as part of developing scientific knowledge and acquiring the language of science. Highlighting familiar tastes, such as foods in the home, is critical in the taste unit. Multilingual learners draw from their own experiences to figure out scientific phenomena.

Use Tools to Create Just-in-Time Language Resources

As students shared ideas about how water changes the land, Billie Freeland used hand gestures to show students’ ideas. She realized that not all students were tracking her movements, so she told them, “This hand is water and this hand is the land.” Then Billie asked the students to use their hands to predict how water in a fast stream could move sand. Now, in small and large group conversation, all students could draw on these gestures to support meaning.

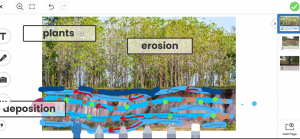

Mary Modaff uses a photograph of erosion to create a shared focus with her students. On the photo, she labels features—like plants and deposition—as they come up in context during discussion. The model is an artifact that can support understanding across contexts, even when some of the students are learning from home, and others are in the classroom.

In these examples, Billie and Mary show how the PBL environment fosters the use of disciplinary language for communication and making sense of phenomena (or natural events). In both cases, because PBL is about doing science rather than being handed ideas, language is developed through hands-on activities.

Best practices in PBL include fostering a shared focus, rigorous content, and scientific practices that enable rich discussion, creating structures for discourse and leveraging home-based knowledge and experiences. PBL practices also align with the 2020 WIDA ELD Standards. All these opportunities can be created simply and don’t require much extra planning time. Project-based classrooms, whether in person or virtual, are highly interactive, with students sharing ideas within a safe community—all key ingredients that support language development.