Teaching Self-Assessment in World Language Classes

Challenging middle school students to take ownership of their learning helps boost their independence at a critical age.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Picture this: You are a seventh-grade Spanish immersion student in my middle school classroom. The lights dim as we open our notebooks to a unit assessment in which you will write an informative text. The learning target centers on how we organize our ideas and how accurately we use our Spanish language skills. But before you scribble on a graphic organizer to plan your writing, you take out a highlighter, and together we look at the rubric for the assignment so that we more clearly understand the criteria for a proficient grade.

Student self-reported grades exceed almost anything else we can do in the classroom in terms of learning outcomes, according to John Hattie’s list of effect sizes. Hattie describes self-reported grades as “student expectations,” or how students predict they will perform on a given assessment. He notes that all too often, students set middling learning goals for themselves, and he asserts that our work as teachers “is to mess that up.” In other words, as teachers, we can change outcomes by coaching our students to achieve at a higher level.

One of the most important ways I do that in my middle school Spanish courses is by teaching self-assessment. In my Spanish immersion classes, self-assessment means that students read and understand the rubric before they begin an assignment, and they use it to report their expected grade after finishing their work.

How Self-Assessment Starts: Read the Directions

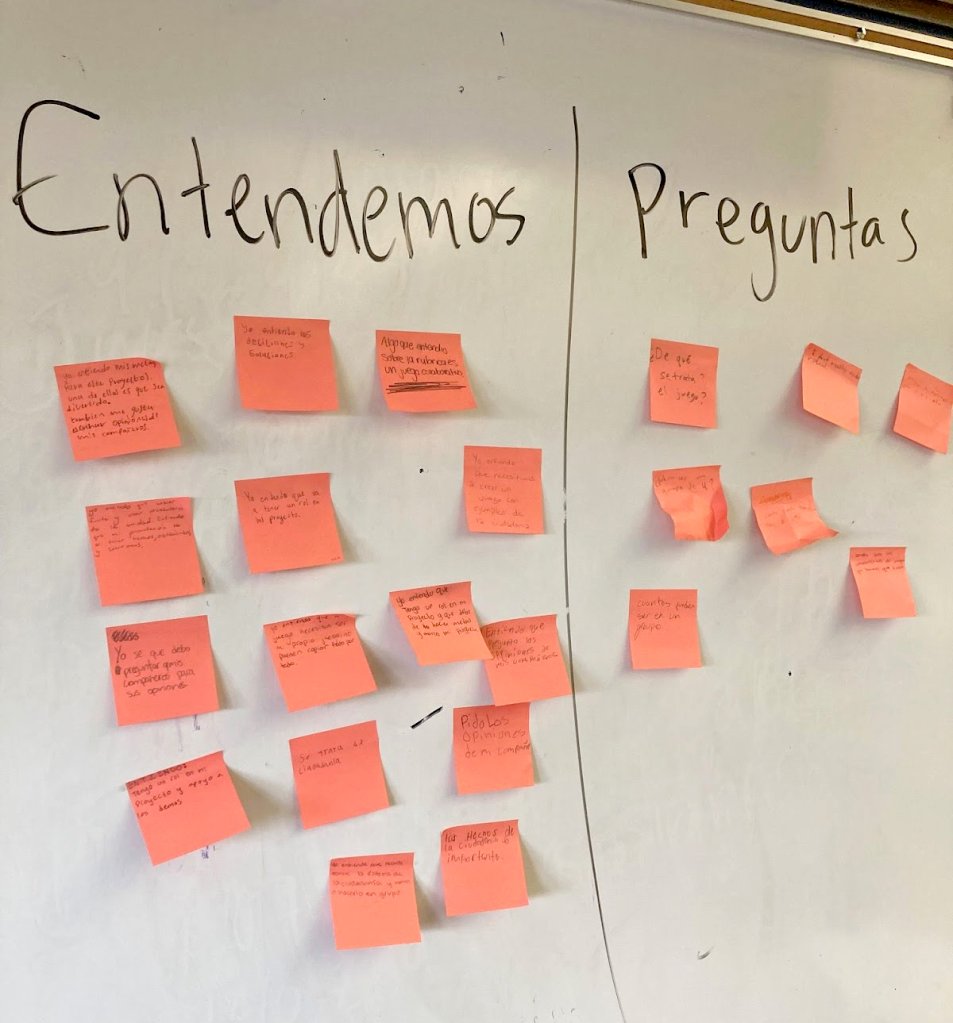

We have all been the teacher who explains in detail the steps of an assignment only to have hands shoot up once we start independent work time: “What are we doing? How do we start?” After a few too many rounds of this, I realized that many of my students remained zoned out when I presented instructions. Now, at the beginning of a task, I provide five minutes for students to read the instructions independently, and then I assess their understanding with sticky notes. Students use two simple sentence starters to give feedback:

- Algo que entiendo es… / One thing I understand is…

- Una pregunta que tengo es… / A question I have is…

To help establish whole-class participation as the norm, I have students post their (anonymous) sentences on the board to create a visual of all that we already know or want to know about the task.

Then I peel off the sticky notes and place them under the projector, reading aloud and briefly responding to each one. This process serves to review the important to-dos in the assignment. It also enables me to answer general questions for the whole class, saving me a half-dozen individual consults. We may also highlight or underline the first step of the assignment so that students can focus their attention on how to start. I notice that when students clearly grasp the directions at the beginning of an assignment, they are better equipped to accurately self-assess their performance when they finish. Rubrics, after all, often serve as a concise reflection of these directions.

Using Rubrics Effectively for Self-Assessment

I ask students to self-assess all of their summative work (e.g., end-of-unit assessments, final essays) and most of their formative work (e.g., collaborative notes, structured discussions). For students to self-assess assignments well, they must understand the grading criteria that we are using. For their self-assessments to be meaningful, our criteria must reflect grade-level standards.

My early attempts at teaching self-assessment were foiled by unnecessarily obtuse wording of rubrics. Students didn’t understand my expectations. Take a look at a sample rubric that I wrote and used during the 2022–23 school year:

Standard: ACTFL Accuracy (Intermediate midlevel)

- Sobresaliente (Exceeding): I make hardly any linguistic errors, and they do not interfere with communication.

- Logrado (Meets): I make hardly any linguistic errors, and they rarely interfere with communication.

- Aproximándose (Approaching): My errors are somewhat frequent and sometimes make communication difficult.

- Necesita práctica (Needs practice): My errors are frequent and make communication difficult.

The vocabulary was technical and teacher-oriented (linguistic, interfere). Additionally, the long, compound sentences didn’t draw students’ attention to the important details.

This past school year, our school-based instructional coach emphasized to our staff the importance of student-friendly language in rubrics. With her coaching in mind, my new rubrics look like this:

Standard: Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings (CCSS 7.L.5).

Sobresaliente (HP/Highly Proficient):

- I underline the two things being compared.

- I explain in a detailed and correct way what the metaphor means.

- I include other relevant details from the text in my explanation.

Logrado (PR/Proficient):

- I underline the two things being compared.

- I explain in a detailed and correct way what the metaphor means.

Aproximándose (CP/Close to Proficient):

- I underline the two things being compared.

- I try to explain what the metaphor means, but my explanation might show some confusion.

Necesita práctica (DP/Developing Proficiency):

- I underline one of the things being compared.

- My explanation shows some confusion or is incomplete.

This example is much easier for my students to understand because it focuses on two specific ways that they will demonstrate the standard: they will underline what’s being compared in a metaphor, and they will explain what the metaphor means. It uses everyday language that we practice in class (underline, detailed), and the actions that students have to take are in bold.

Putting the Pieces Together

Teaching self-assessment has benefited my students and me, and it is a worthwhile pursuit in any classroom. In most cases—anecdotally, I’d say eight out of 10 assignments—students’ self-graded work accurately anticipates the grade I would have provided.

It’s worth noting, though, that student self-assessment does not have to be flawless to be functional. A student might not know that their interpretation of a metaphor is misguided, and they may mark their explanation as correct or proficient. In world language classes in particular, students may struggle to self-assess linguistic accuracy—if a student knew that a word was misspelled or misconjugated, they probably would have written or said it differently. Nonetheless, students are still well-served by making their best attempt at self-assessment because it encourages them to reflect on their work.

Does it change predictable outcomes, though? Does it shift the needle, even a little bit, for students who might otherwise settle for less? For me it has, and I suspect that it might have something to do with the very adolescent impulse to fit in.

I saw this firsthand one day when our instructional coach helped me explain a rubric to my class. As she described the criteria for proficiency, she said, “Do you see? This is where we expect you to be as seventh graders.” By reinforcing grade-level performance as the expectation, she was “messing up,” in Hattie’s terms, my students’ safe forecasts for themselves. Now, when students want to circle “developing proficiency” or “close to proficiency" on the rubric, they show more motivation to keep going so that they can show off what a seventh grader can do.