Making Sure Your Students Are Actually Processing Feedback

Grading papers at 2 a.m. in her living room became one teacher’s new normal—so she decided it was time to reinvent the way she gives feedback.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.When her 3-year-old daughter would wake from night terrors, writing and English teacher Elizabeth Matlick would first help the child settle down, then round out her predawn hours by grading papers for her approximately 100 middle and high school students. She confided the story to a friend, but got an eyebrow raised in concern in response. “My challenges with the feedback load were officially impacting my health and family life,” Matlick writes for EdSurge.

“What started as a journey to keep up with the paper stack and to cajole my students into revising their work, [became] more about helping students manage, engage with, and productively process the different kinds of timely feedback available to them,” she writes.

Initially, she implemented several techniques—peer reviews, self-assessments, and writing reflections, for example—that would supplement her own guided feedback and also immediately help alleviate some of her workload. Instituting a new peer review approach helped her get a handle on how students were using “teacher-developed criteria to evaluate one another,” she says, and showed her which students weren’t really grasping all the feedback she had been providing. “I could see which students needed direct support from me, and I was able to provide more targeted whole-class feedback.”

But that didn’t solve the nagging issue of why some of her students still weren’t incorporating feedback to improve their work. With the help of a colleague, Matlick landed on the revelatory research of U.K.-based cognitive scientist Naomi Winstone who, in identifying barriers students face when they encounter feedback, found that emotions play a pivotal role. Perhaps the anxiety and the emotional cost of hearing and acting on feedback was stopping her students in their tracks—maybe it wasn’t just the technical difficulty of improving their writing.

“This insight officially redefined the problem for me,” says Matlick. “Rather than offering detailed summative feedback, which comes too late for learning, or focusing on a single intervention, like peer review, I needed to support my students in a broader series of meta-cognitive skill building to support their feedback literacy.” Instead of thinking of feedback as one-directional, Matlick was determined to make it a conversation that her students actively sought out: “I needed to help them seek and understand feedback so they could use it to learn.”

EXPLORING EMOTIONAL OBSTACLES

To help her students dig into their feelings about feedback, Matlick gave each child a Post-it note. The responses she received from them indicated that they often experienced fear, for example, or approached the feedback with their defenses up.

“I asked them to jot down how they feel when they’re about to receive feedback. The conversation was eye-opening,” she said of this easily replicable strategy. “I realized that I had no idea how my students felt about feedback—I never stopped to ask.”

HELPING STUDENTS REFRAME FEEDBACK

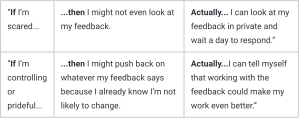

Building on the feelings students wrote down as a starting point, Matlick followed up with a brainstorming session using an “if…then…actually” framework to help her students work through how they might do a better job grappling with, and then incorporating, feedback.

Looking at the chart, which progresses from reading the feedback, to acknowledging the anxiety it provokes, to mastering their emotions and acting on the suggested changes, Matlick concludes: “I stressed how easy it can be for all of us to get stuck in the middle column for too long and miss out on making our work stronger.”

PRACTICING HOW TO MANAGE EMOTIONS

Not yet satisfied, she continued to search for other concrete ways to help her students manage emotions and understand their own responsibility when it comes to feedback. Matlick eventually came across research by Victoria Black about improving people’s response to feedback. “I loved how Black characterized the role of the learner: ‘The mentee is the driver and the mentor is the co-pilot, helping them get to their destination’.” It reframed the feedback as a symbiotic dynamic, with both the receiver and the giver of feedback accountable in their own ways.

Based on that research, Matlick had her students role-play in pairs, with one child pretending to drive (receiving feedback) and the other pretending to be a driver’s ed teacher (giving feedback), while she threw questions at them such as: “Who’s responsible for the feedback and learning here? … What if the student driver felt scared in this situation? … How should she communicate that to her teacher, the feedback giver? And, what might happen if she didn’t communicate at all?”

The exercise helped her students realize the importance of responding to feedback and, equally important, clearly communicating their needs as they relate to receiving, understanding, and processing feedback. The outcome, Matlick observes, was a greater sense of agency for her students.

Effective, timely, and targeted feedback that truly helps students improve their writing, she concludes, should be a “team effort forged in the classroom. And when it’s working really well, it’s driven by my students.”