A History in Which We Can All See Ourselves

Educators are finding ways to tell a richer history of America—responding to the demands of an increasingly diverse student body.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.After a recent assignment on Christopher Columbus’s expedition to the New World, a student approached eighth-grade teacher Vanee Matsalia after class. The girl, whose family is from the Caribbean, told Matsalia that the lesson was the first time she had heard her people mentioned in school.

“‘I can’t wait to go home and tell my dad—he’s going to be so excited, but so angry when he finds out what happened,’” Matsalia remembers her saying, referring to Columbus and his fellow colonizers enslaving and killing many of the indigenous people they encountered when they landed.

Matsalia teaches English language arts (ELA)—not history—but for the past seven years, she has been working hand-in-hand with a history teacher at her largely black and Latino Title I middle school in San Bernardino, California. Together, they co-teach units in which students probe into a complicated U.S. historical narrative, one that highlights stories of populations and events often left out of history books. Students then research, write, and build projects about these “other” perspectives in ELA.

“I hear from students all the time, ‘Why have I never seen this before?’ They are often in shock,” said Matsalia of the course. “The lessons resonate when connected to something students can belong and respond to.”

Matsalia is part of a growing group of educators working to expand K–12 history curricula to include the narratives of people from a wider range of racial, ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds at a time when schools, and the country, are becoming rapidly more diverse. These changes in coursework are happening in synchrony with others—like a shift away from punitive discipline and a focus on social and emotional learning—aimed at making schools more culturally responsive and attuned to the whole child.

Focusing on Research

Proponents of greater inclusivity in history say that when young people see themselves in the story of our shared past, they not only develop a deeper appreciation of the subject but become more civically active, citing research indicating that students who feel a sense of belonging and identity in school are more likely to be engaged in society more broadly.

Research also shows that the self-image of students can suffer when they regularly encounter negative depictions of people who look like them. And a 2010 study of ninth- and 10th-grade students extends that insight to omissions, finding that girls performed significantly better on a chemistry quiz when the textbook lessons featured images of only female scientists, while the performance of boys declined under the same conditions—leading the researchers to conclude that the simple act of representation can level the playing field.

Unfortunately, progress in social studies curricula has been slow moving. A Rutgers University study found that while social studies courses are “pivotal sites” for promoting civic engagement in young people, schools with high percentages of students of color and low-income students tend to have “the least innovative and most ineffective” social studies courses. As a result, students frequently find the study of history and government “alienating and irrelevant,” or they see a disconnect between “civic ideals and the reality of their lives.”

Changing Requirements

There may be changes ahead. The Philadelphia district made it a requirement for students to take at least one African American history class to graduate. Montana, Washington, and Wisconsin now mandate that Native American history be taught to students, while New York, New Jersey, Florida, and Illinois have put laws on the books requiring all students to study the Holocaust and other genocides. And in 2011, California passed legislation requiring districts to include the roles and contributions of people with disabilities and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in state social studies curricula.

These requirements have not involved the removal of key historical figures like Thomas Jefferson, as skeptics have warned or fretted.

In California, the history curriculum guidelines and materials weave in the contributions and sexual orientation of LGBTQ historical figures like Walt Whitman, and significant events in LGBTQ history like the Stonewall Riots, which have often been missing from schools’ history curricula. And the 11th-grade standards, for example, address familiar themes like the rise of America as a superpower and the contributions of key leaders like Theodore Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, but also discuss the roles of African American soldiers during World War II and the Lavender Scare that targeted LGBTQ government officials during the 1950s.

"The more people understand other perspectives and the more we include underrepresented people in history, the more they are legitimized as American history,” says Shana Brown, a middle school teacher in Seattle Public Schools who helped write the Native American history curriculum for Washington state.

As a teacher in the 1990s, Brown, who grew up on the Yakama Indian Reservation, began weaving Native American history into her coursework because it was absent from textbooks. Hoping to take this work one step further, Brown traveled to the capital and got involved in efforts to change Washington’s history curriculum. In 2005, legislation passed recommending that schools include tribal history; by 2015, it had become a requirement.

“I went through all of school and college thinking my history wasn’t relevant or I didn’t have one. When I became a teacher, I realized that our history does matter and my history is American history,” said Brown, who still teaches and was recently recognized as a Great Educator by the U.S. Department of Education.

Upstanders

But for teachers and districts that want to refresh their history materials, there can be a difficult trade-off, according to Tim Bailey, education director at The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, a nearly 25-year-old nonprofit dedicated to K–12 American history education.

Bailey said teachers often have to perform a balancing act between meeting state history standards that are politicized and slow to change, and trying to teach history lessons that a diverse range of students will find meaningful—placing the onus on the teacher to seek out additional teaching materials. “Do you teach a mile wide and an inch deep? Or do you go for depth and understanding?” Bailey said. “Those are hard decisions for teachers to grapple with.”

Due to states’ evolving requirements and interest from teachers, schools and communities are thinking creatively about how to work together.

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie now collaborates with schools, for example, welcoming 62,000 schoolchildren and educators annually to learn about the history of genocides around the world. A recent study found that 66 percent of millennials did not know what Auschwitz was. The museum has also hosted sold-out professional development sessions on topics like “Difficult Conversations,” which helps teachers discuss events that may make both students and educators uncomfortable.

“The purpose of learning about what led up to the Holocaust is not just to remember the past, but to transform the future,” said Shoshana Buchholz-Miller, vice president of education and exhibitions at the museum. “Students can then look at what’s happening in their society, or even on their playground, and they are equipped and empowered to be what we call an upstander, not a bystander.”

Hitting Refresh

But according to experts, teachers should also look around them for easily accessible resources and materials to make history more inclusive—and sometimes, those are found in their own communities or classrooms.

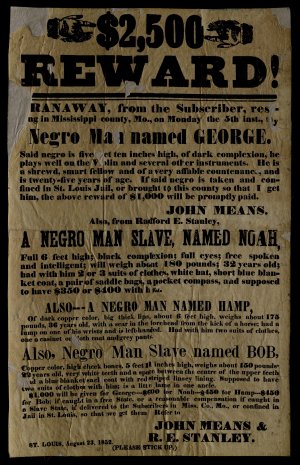

Using Gilder Lehrman’s massive, free online collection of primary source materials, teachers can help students connect to the experiences and emotions of the people in the stories—especially ones who look like them. This may mean reading a poster written by women in the early 20th century discussing the importance of having the right to vote, a flyer for a slave auction, or a letter urging people to vote for an African American vice presidential candidate in the late 1800s.

It can also mean hitting refresh on old materials. In her winter unit on the book A Wrinkle in Time, Matsalia used the main character, Meg, to walk her students in San Bernardino through issues of gender representation and traditional gender roles at the time the book was published in 1962. She asked students to consider whether one character referred to is a trans person—and then they discussed how history has viewed trans people and how society views them today.

Finding new course materials may also involve looking around locally. With support from the nonprofit Facing History and Ourselves, Dr. Marilyn Taylor taught her students at Overton High School a lesson on how Reconstruction led to racial violence like lynchings, which motivated students to see if any lynchings had occurred in Shelby County, Tennessee, where their school is located. After finding that one had happened less than 20 minutes from their school, students banded together to mark all the local lynchings and held memorials at each site for the victims.

Now a freshman at the University of Memphis majoring in psychology and criminal justice, Overton alum Khamilla Johnson said that she often reflects on lessons learned during the memorial project, which helped influence her future choices.

“I think about [Dr. Taylor’s class] all the time, because it really helped to shape my character and gave me a position to use my voice,” said Johnson, who hopes to one day join the FBI. “Dr. Taylor reminded me that I do have a voice, that I can speak out about things that matter and make a difference.”

Photograph of Neta Snook with airplane, circa 1920. (The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, GLC07243.006.03)

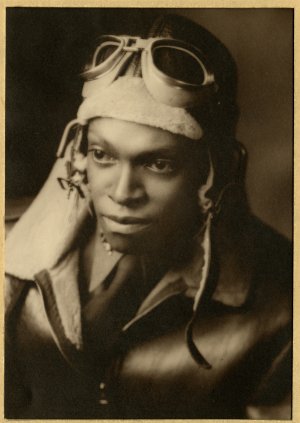

Polk’s Studio, Photograph of LeRoi S. Williams. (The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, GLC09587.416)

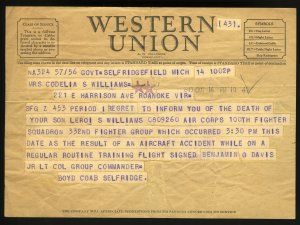

Boyd Coab to Cordelia Williams, October 14, 1943. (The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History,GLC09587.402)

$2,500 Reward! Missouri Co., Missouri broadside advertising runaway slaves, August 23, 1852. (The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, GLC07238)