A Simple Activity to Boost Students’ Observational Skills

By providing students with time to draw and discuss leaves, teachers can help them learn to observe deeply and connect with their surroundings.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Children are naturally inclined to seek patterns in, categorize, and classify information around them. Teachers can take advantage of this tendency as a way to help students study, examine, and explain their findings about the world around them. In my classroom, I leaned into this idea through a project I like to call a natural history collection: a set of related artifacts that students study. My chosen artifacts? Leaves. This project allows students to build important scientific skills with a relatively low lift, since students are using a resource found all around us outside.

WHY CREATE A COLLECTION OF LEAVES?

Leaves are everywhere, are easily collectible, and can be examined without hurting the plants. When I was trying to think of an artifact for my students to study, this quickly became my favorite option. In addition to their ease, leaves provide students with an opportunity to study how plants operate.

By studying leaves in depth, students can develop a stronger understanding of scientific classification, plant evolution, and comparative plant anatomy. This understanding can then translate into the larger context of understanding natural selection and important ecological principles such as primary and secondary succession. Maybe more important, by studying leaves through the activities explained below, students learn to really pay attention to the world around them.

LEAF COLLECTION

To begin creating your natural history collection, students create representations of the leaves they’ve collected. Depending on your students’ age and your surroundings, either you can choose to go outside as a class to collect leaves, or you as the teacher can do this in advance and bring them into the classroom for students to choose from.

If students will be collecting the leaves themselves, it is important to remind students to be respectful to the plants:

- Whenever possible, collect recently dropped leaves.

- If the plant has only a few large leaves, those should not be taken, as that can cause tremendous long-term damage to the plant.

- Flower petals should not be plucked from plants, as those are metabolically irreplaceable for the plant.

LEAF SKETCHING

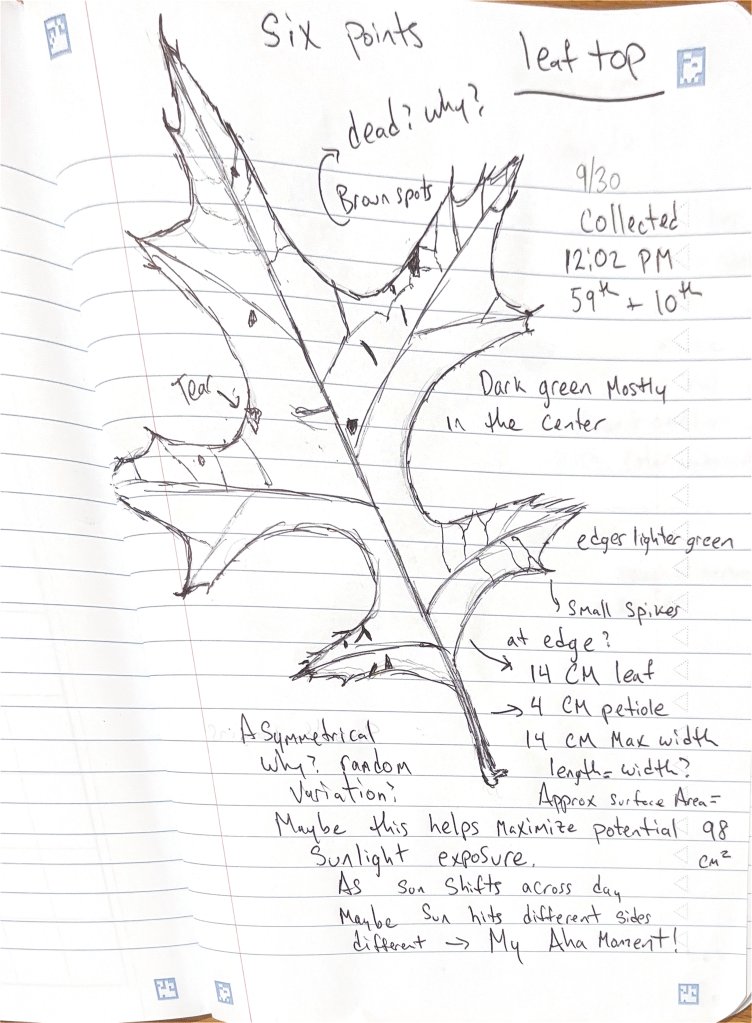

For this first activity, students will look at their leaves and sketch them with as much detail as possible. Sketching forces students to spend a long time looking at what is in front of them, helping them recognize small details that might otherwise have gone overlooked. As students sketch their leaves, they should also write out what they are drawing and what they notice: How do the edges of some leaves differ from others? How are the leaves shaped? What colors are present in the leaves?

It can be helpful to provide students with rulers and different-colored pencils for their sketches and observational notes. Encourage students to use scientific language as they write their notes. It can also be helpful to provide anchor charts or word banks for students to refer to as they are working.

As students continue sketching and observing, you can prompt them to begin thinking about how the leaf’s shape helps the plant it belonged to survive. As students continue to make observations and answer prompts, teachers can lead students in group discussions to share their findings.

LEAF RUBBING

In addition to sketching, you may want to encourage students to try leaf rubbing, as it offers an opportunity to accurately capture all the nuances of the leaf. To create their leaf rubbings, have students place a leaf underneath a piece of paper and, using the side of a pencil or crayon, gently rub back and forth to imprint the leaf’s pattern onto the paper. Using different types of paper and writing tools can help students create different versions of the same leaf.

Leaf rubbing should not be a substitute for leaf sketching, as both offer students the opportunity to notice nuances in different ways. In my classroom, I always encourage students to do a combination of both and examine as many different leaves as possible so they have a large sample size from which to make generalizations.

Students may make observations or pose hypotheses about the types of leaves that survive the longest on a plant, the ways in which shape may impact the plant’s ability to survive, and how they can identify a plant based on its leaves.

SHARING THEIR FINDINGS THROUGH AN EXHIBIT

Sharing observations is a pivotal component of science communication. After the class has completed a substantial analysis of leaves through their visual representations and written observations, it is time for them to share their findings.

In the back of the classroom, I set up my exhibit space where students each posted their drawings, their leaf rubbings, and their written observations. In addition, students labeled their drawings with the name of the plant if they knew it, where and when the leaf was collected, and a description of the leaf’s components using scientific terminology.

Once all students posted their information, I asked students to explore the exhibit, taking time to notice what their classmates had found. Students wrote their own observations and questions in their notebooks and talked to one another as they looked at the leaves and the information.

After exploring the exhibit, students and I discussed general findings, questions that came up, and ideas for future exhibits. Students were engaged in the entire process and excited to share their observations. While I couldn’t necessarily answer every question they posed, the important thing was that they were asking thoughtful, scientific questions. This activity builds upon their natural curiosity and allows them to explore both independently and as a class.

We often think that science classes have to focus on the exotic. There is nothing wrong with learning about far-off rainforests and deserts, but a tremendous amount of valuable scientific observation can occur with what is overlooked all around us. There is magic in the mundane if we teach students to pay close attention to what is nearby.