5 Ways to Encourage Deep Mathematical Thinking

You can adapt the curriculum you have to create rich tasks that invite reasoning and build students’ problem-solving skills.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.I know that teachers play the most significant role in any learning situation, and studies have shown that investing in teacher learning is more important than investing in new curriculum, books—or anything else. I also know that the best learning outcomes happen when teachers have autonomy to choose tasks, adapt tasks, and bring in new tasks.

But what should you be looking for when choosing tasks? And how do you adapt tasks to meet the interests and needs of the students in your class? So many math teachers are told to use textbooks that are filled with short, narrow questions that don’t interest students or create opportunities for deep or critical thinking.

Engaging Tasks Make Math More Interesting to Learn

I started my career as a math teacher in London, in inner city schools, but I’ve spent the last few decades studying math teaching and supporting teachers through the Youcubed website, which shares thousands of free resources that help students learn math and data through engaging and creative tasks.

In my recent book, Math-ish: Finding Creativity, Diversity, and Meaning in Mathematics, I make a plea to go beyond the narrow math that has turned students off for generations, and enhance it with rich tasks that invite reasoning and problem-solving. Although this approach to math can be really helped by a good curriculum or book, teachers can create a much better mathematical experience by adapting their approach to the materials they have been given.

When I do this work, I draw from a set of five principles that I think are worth sharing here.

5 Ways to Create Powerful Mathematical Experiences

1. Before a student answers a question, ask ‘What is your “ish” number?’: Educators have valued estimation for years, but it is usually taught as a method in elementary school, and students often hate to perform estimations. But when we ask them, “What is your ‘ish’ number?” something different happens: Students think more conceptually, and they enjoy thinking “ishly.” This classroom video shows the approach in action.

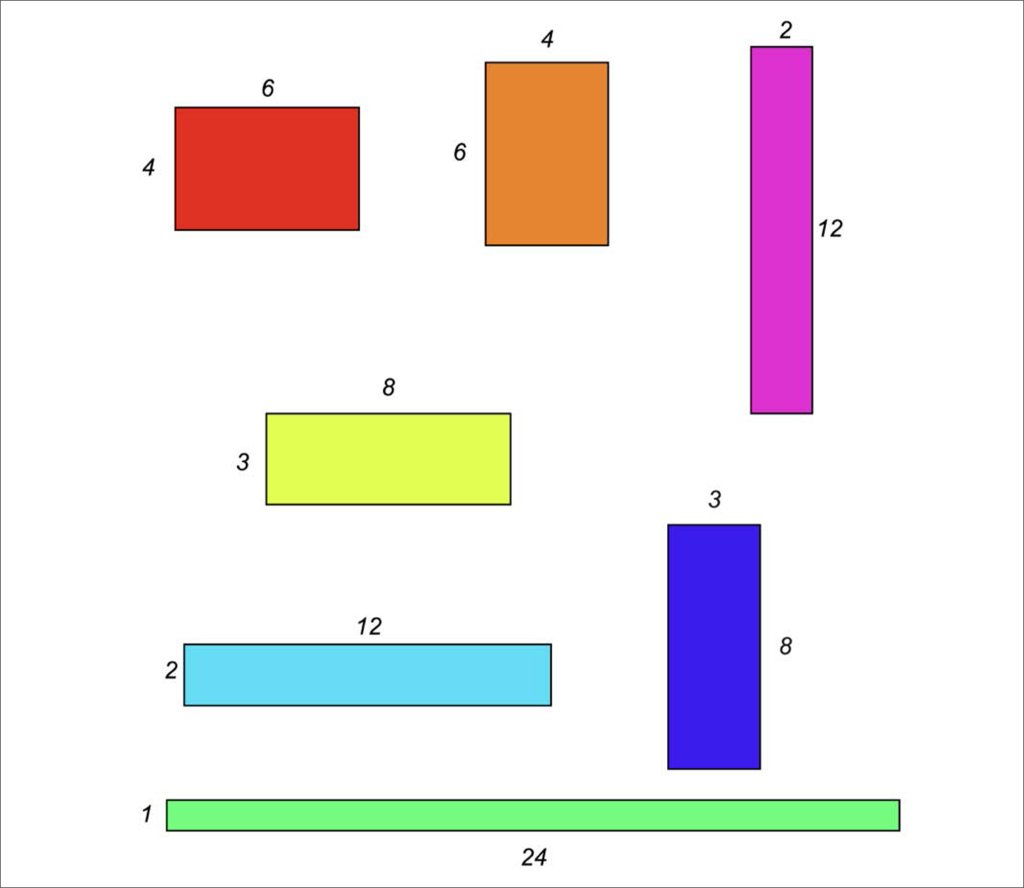

2. Make many possible answers valid instead of only one: Open up the question with a simple reversal. Instead of asking students to find the area of an 8 x 3 rectangle, ask them, “How many rectangles can be made with an area of 24?” This question guides students to consider the relationship between length and width and think visually.

3. Change what you ask students to do: Textbooks are filled with questions that ask students to “fill in the answer,” “solve the multiplication,” or “complete the division.” These questions use imperative verbs—telling the students what to do. Reasoning is the essence of mathematics, but questions like this don’t ask for reasoning and suggest that it’s unimportant. It’s easy to change what you ask students by using action verbs in your questions. For example:

“How would you approach this question?“

“Can you draw or build it?“

“Why does your approach work?”

“Can you prove it to me?“

“Can you make a visual proof?”

All of these questions invite students to reason about mathematics, and some invite students to visualize ideas. Both are extremely important.

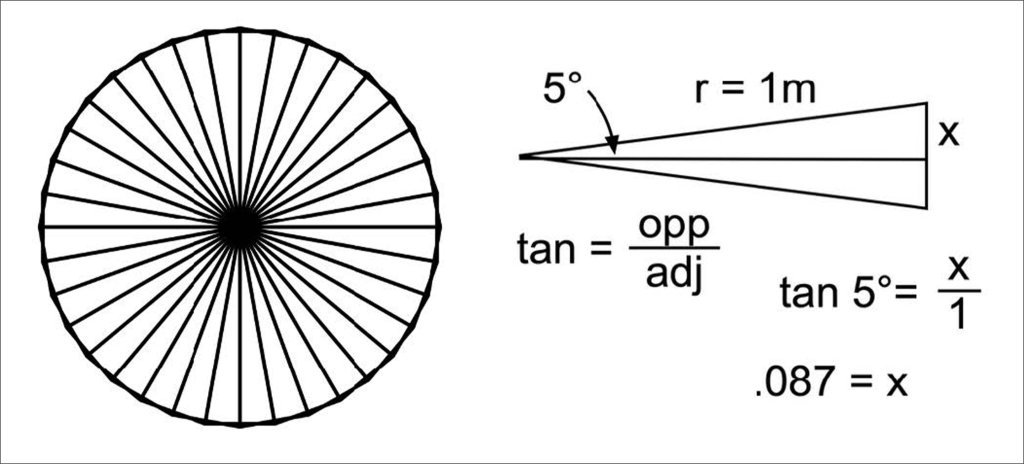

4. Ask the question before teaching a method: Ask students to use their intuition to think about a problem before showing them how to solve it. For example, asking students to find the maximum area of a fence made of 36 smaller fences will give students an opportunity to use trigonometry. Many teachers would show the students trigonometry methods and then give students the problem. Instead, you can ask students to explore the problem and use their intuition. They can draw the problem, possibly building the fence with toothpicks or thinking of other methods to solve it.

Possible student methods:

In the example below, the student divides the shape into 36 triangles and uses trigonometry to find their area.

When students need to use trigonometry, that’s a good time to share the ideas inside the problem. When students need a method, and it is taught to them in that moment, they’re more interested in the ideas and more likely to learn the ideas deeply.

5. Ask less and get more: If you’re faced with a series of short, narrow questions from a prescribed textbook, choose one or two of them and open them up in the ways suggested above. Ask students to work together in groups, to reason and visualize their way through the problems.

My team and I have been working with the Healdsburg district in Sonoma County, California, for the last 10 years. When we started working with the district, approximately 16 percent of fifth graders were proficient in math, with similar proportions in other grades. The district developed a “math innovation” plan and started to make great changes.

The teachers shared mindset ideas and used open, visual tasks (like the ones described above) each month, and students regularly worked in groups. Most important, teachers didn’t choose a new curriculum. They started finding good tasks and adapted others to create their own set of materials that engaged the students in reasoning and collaboration. Last year, the number of students in fifth grade reaching proficiency had increased from 16 percent to 75 percent.

At this point in time, many districts in California are working out which math curriculum to adopt for the next few years, following the adoption of the new California Mathematics Framework. They often do this because previous curriculum materials weren’t successful. But new curriculum materials will also be unsuccessful if they don’t offer students the opportunity to reason about mathematics and to visualize. The best use of district money, in my view, is to invest in teacher learning and support teachers in choosing, adapting, and improving math tasks.