13 Tips to Quickly Deliver Super Effective Feedback

These efficient feedback strategies support student learning without sacrificing a teacher’s nights and weekends.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Giving students meaningful feedback is one of the most powerful moves that a teacher can make—but it can also be one of the more time consuming aspects of the job.

Between large class rosters, limited planning time, and the pressure to keep instruction humming along, the specific, actionable, and timely feedback that moves the needle on student growth can often feel like a pipe dream. Written comments pile up, grading bleeds into nights and weekends, and students often receive the guidance they need long after they’ve stopped thinking about the work.

This doesn’t have to be the case. Teachers across subjects have devised smart, time-saving approaches to provide students with swift, highly effective feedback without burning themselves out in the process. This includes strategies like turning common errors into whole-class learning, batch grading work, using voice notes to deliver quick, compelling writing feedback, and convening micro-conferences centered on a single learning goal.

Here is a collection of teacher-tested, fast, flexible moves to try that can make quick feedback clearer for students and more sustainable for educators.

Target One Skill at a Time: Matthew Johnson, educator and author of Flash Feedback, says teachers get better results—and save themselves some time—when they periodically design assignments around a single learning objective and give feedback only on that skill.

For example, when his students struggled with commas, he created a short “comma paper” where students wrote about any topic they wanted but had to include four correct examples of comma use. Johnson locates commas instantly in Google Docs and inserts quick, pre-loaded responses: praising accurate usage or asking students to revise. The latter camp gets a chance to revise immediately, applying the feedback while it’s still fresh—a process that Johnson says produces far more growth than a year of tediously circling comma errors on papers.

Remember the “We Do”: In the typical “I do, we do, you do” progression, some teachers don’t take full advantage of the “we do” part—which is a good time to spread the responsibility of feedback, and shorten the turnaround time, according to instructional specialist Miriam Plotinsky.

Instead of modeling an approach and asking students to run with it, let them make first attempts collaboratively in small groups with teacher support and reflection built in. In ELA class, students might first draft a thesis statement in small groups, compare it against shared success criteria, and revise it with quick feedback before writing one on their own later. In math, the first part of a multi-step equation can be solved as a group, with a teacher talking through the initial steps afterwards, before students finish independently. This creates opportunities “for discussion around areas of confusion,” Plotinsky says.

Add Audio Comments: Written, individualized, idea-level feedback is time-consuming, but delivering that same feedback audibly is much faster, says literacy researcher and Texas A&M associate professor Debra McKeown.

Instead of marking up drafts or lab reports, teachers can record feedback as short audio notes. High school English teacher Cathleen Beachboard, for example, uses tools like Mote’s or Google Doc’s voice comments to record feedback notes on student papers. She keeps each note focused on one specific strength and actionable next steps. Before recording, she jots down the points she wants to hit, then speaks conversationally—just as she would in a quick conference. The approach is faster, more personal, and students love it: “It felt like you were actually talking to me, not just writing on my paper,” said one of Beachboard’s students.

Live Writing: High school English teacher Tanner Jones targets one or writing two skills at a time and gives students the writing feedback they need while they’re still in the process of drafting during “live writing” sessions.

Jones sets aside in-class writing time, has students draft their work in shared documents, and toggles between their screens to offer quick, targeted comments in real time. He focuses feedback only on the skill being taught—whether it’s introducing evidence or crafting a thesis—and in about 30 seconds, he can nudge a student in the right direction with a concise comment like “try making a clearer, defensible claim.” Students see suggestions instantly, and revise immediately.

“My Favorite No”: High school math teacher Rachel Fainstein uses this strategy as a fast, low-stakes way to give whole-class feedback on common math misconceptions.

Fainstein pulls an anonymous student sample—often from the previous day’s exit ticket—that includes a typical but interesting error, like mixing up slope and the y-intercept. The routine begins with the positive: “What did this student do correctly?” Before turning to: “What could the student have done better?” Students identify the misconception and individually correct the full problem. Because the focus stays on the reasoning, not the student, this creates a quick, communal feedback loop—students see how others think, learn to justify their corrections, and view mistakes as essential to learning.

Be ‘Wise’: Research shows students are more likely to act on feedback when it is paired with “wise interventions,” or brief, genuine gestures of confidence or connection.

Johnson taps into these findings to heighten the effectiveness of his comments without overly taxing his workload by adding short personalized statements to feedback. For example, an English teacher might write, “You made real progress with your evidence here—I know you can take the next step with your analysis,” before offering a targeted suggestion. A math teacher might add, “I’ve seen you tackle tougher problems than this. Let’s fix the setup and try it again,” to help a student reframe a mistake as solvable. These tiny signals of belief take seconds to add but can dramatically increase a student’s receptiveness to feedback.

Speed Up Feedback with Sentence Stems: When staring down a large stack of assignments, Beachboard recommends using pre-written sentence stems to systematically speed up feedback without sacrificing quality. Instead of inventing new phrasing for every student, Beachboard keeps a bank of short feedback starters like: “Your claim is clear,” “To strengthen your argument, consider…” or “I noticed ___. Next time, focus on___.” These stems help her quickly deliver precise, actionable comments.

Use “Here’s What, So What, Now What”: Instructional coach Kathy Collier uses this quick, three-step protocol to deliver clear, actionable feedback without slowing down instruction.

She starts with “Here’s What,” a brief, objective statement describing what a student did—for example, telling a third grader practicing academic discussion skills, “You asked Sofia what evidence she was using for her claim.” The “So What” names why the move mattered: “Your question prompted everyone to look back at the text and add to the conversation.” Finally, the “Now What” lays out one or two next steps students can apply: “Next time, try to add on to what others say during the conversation, too.” Because the protocol is simple and fast, Collier can use it in the flow of a lesson, offering meaningful feedback in under a minute. Sentence starters like “I agree with you and would add ___” give students even more tools to act on the feedback right away.

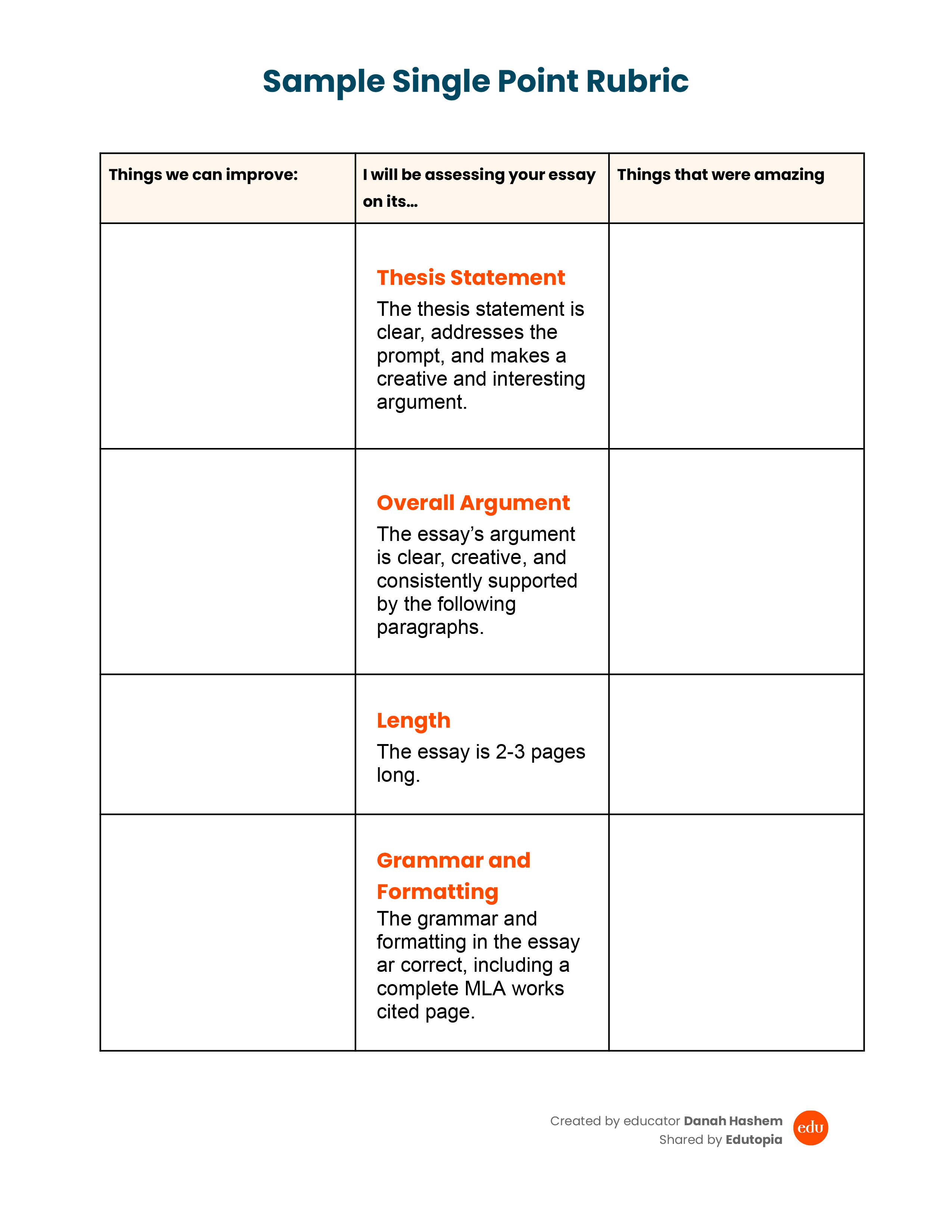

Single-Point Rubrics: Instead of overwhelming students with multiple categories and point values—and burdening herself with multiple points of assessment in one paper—high school Beachboard uses streamlined, single-point rubrics.

Beachboard makes a simple three-column rubric. Down the center she writes short “success criterias” for a handful of targets, such as an essay’s thesis statement or the strength of its arguments. In the two side columns, Beachboard notes where students exceeded expectations or fell short. The paired down rubrics aren’t just about simplicity: “By focusing feedback on one clear target at a time, we align with what working memory can handle,” Beachboard says. “Instead of juggling six criteria, students can direct their mental energy to the area that matters most.”

Micro-Conferences: One-on-one conferences are highly effective—but eat up time. Johnson’s solution is the micro-conference: a 1 to 2 minute conversation centered on a single learning goal.

Before meeting with him, students assess themselves and write a few sentences about their work, building their metacognitive skills and helping them articulate what they’ve done well and where they’re struggling. During the micro-conference, Johnson asks pointed questions, nudges students toward clearer reasoning, next steps, and resources. By keeping the conversation brief and targeted, he can meet with many students in a single class period while the rest of the class works independently.

Holistic Sorting: Grades alone don’t give students the feedback they need to improve, says Plotinsky, who encourages teachers to build in low-stakes, ungraded work designed specifically to inform instruction and guide feedback.

A sixth-grade science teacher, for example, might assign a quick assignment to see whether students can identify mutually beneficial ecosystem relationships. Instead of grading each response, Plotinsky suggests sorting them into two piles: assignments that meet expectations and those that don’t. In the “not yet” pile, Plotinsky focuses not on correcting every mistake, but looking for patterns to identify larger, shared misconceptions. These trends can inform instruction and help students get quick, actionable feedback to improve their understanding.

Pause Mid-Lesson to Address Mistakes: When students work independently and teachers circulate around the room, patterns of errors often emerge—such as several students forgetting to distribute a negative across parentheses in math, or writing incomplete chemical equations in chemistry.

Instead of trying to help students individually, Collier suggests pausing a lesson to recreate a common mistake and huddling with the classroom to address it. This might take the form of a large discussion, or smaller group discussions. Once the fix has been made and discussed, Collier turns students back to their own work to “ensure that they don’t have any of the same mistakes.” This mid-lesson pivot keeps misconceptions from spreading and delivers quick feedback at the moment students need it.

Pattern-Based Feedback: When students are early on in the drafting process of a paper, high school English teacher Dave Stuart Jr. occasionally uses a revision priority list to give students the high-level guidance they need quickly, and without having to write endless margin notes.

This whole-class feedback strategy that targets the most common issues in a curated selection of early drafts. Stuart reads just 10 or so papers from a full class set and looks for repeating patterns, for example, weak thesis statements, vague evidence, or choppy transitions. He then turns those patterns into a short, focused lesson the next day, showing examples of the issues, and quick fixes, an approach that gets students the timely, high-leverage feedback they need to effectively revise their work without delaying the process by waiting for him to grade every single draft individually.