The Pros and Cons of Homework (in 6 Charts)

The case for homework isn’t black-and-white, so we looked far and wide for research to shed a little light on the matter.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.The value of homework is one of education’s most heated debates—and one of its most misunderstood.

For some, homework reinforces learning while building study habits. For others, it’s unnecessary busywork that fuels stress and disengagement.

Decades of research, however, suggest that the truth lies somewhere beyond these binary distinctions: Homework has increasing value as students climb through the grade levels, and that’s especially true in high school, once time-management skills are in place. For younger students, the gains, when they can be spotted at all, are more nuanced—but at any grade level, from elementary to high school, poorly designed tasks or rigid homework policies can create more problems than they solve.

“Homework is a practice full of contradictions, where positive and negative effects coincide,” researchers explain in a 2017 study. Purposeful, well-designed assignments can extend classroom lessons while helping students manage their own learning. Daily at-home reading, research shows, can deliver meaningful, long-lasting benefits to literacy.

Balance and teacher discretion is crucial: A growing body of research reveals that excessive homework displaces activities that support healthy development, from sleep and family time to hobbies and friendships, and can significantly increase unhealthy stress levels—all of which can take a toll on student engagement and mental health. Finally, not all students have equal access to the tools needed to complete assignments, especially as more schoolwork shifts online.

Here are six charts that shed light on the ways that homework helps or hinders, bringing a research lens to an admittedly tough conversation.

A Significant Boost for Older Students, a Foundation for Younger Ones

Less is more for novice learners—and well-crafted assignments are key.

When people make a no-homework-ever argument, it’s often based on a binary interpretation of the research: Homework is bad in the early grades and better as kids get older—but it’s generally of negligible benefit across the grade bands.

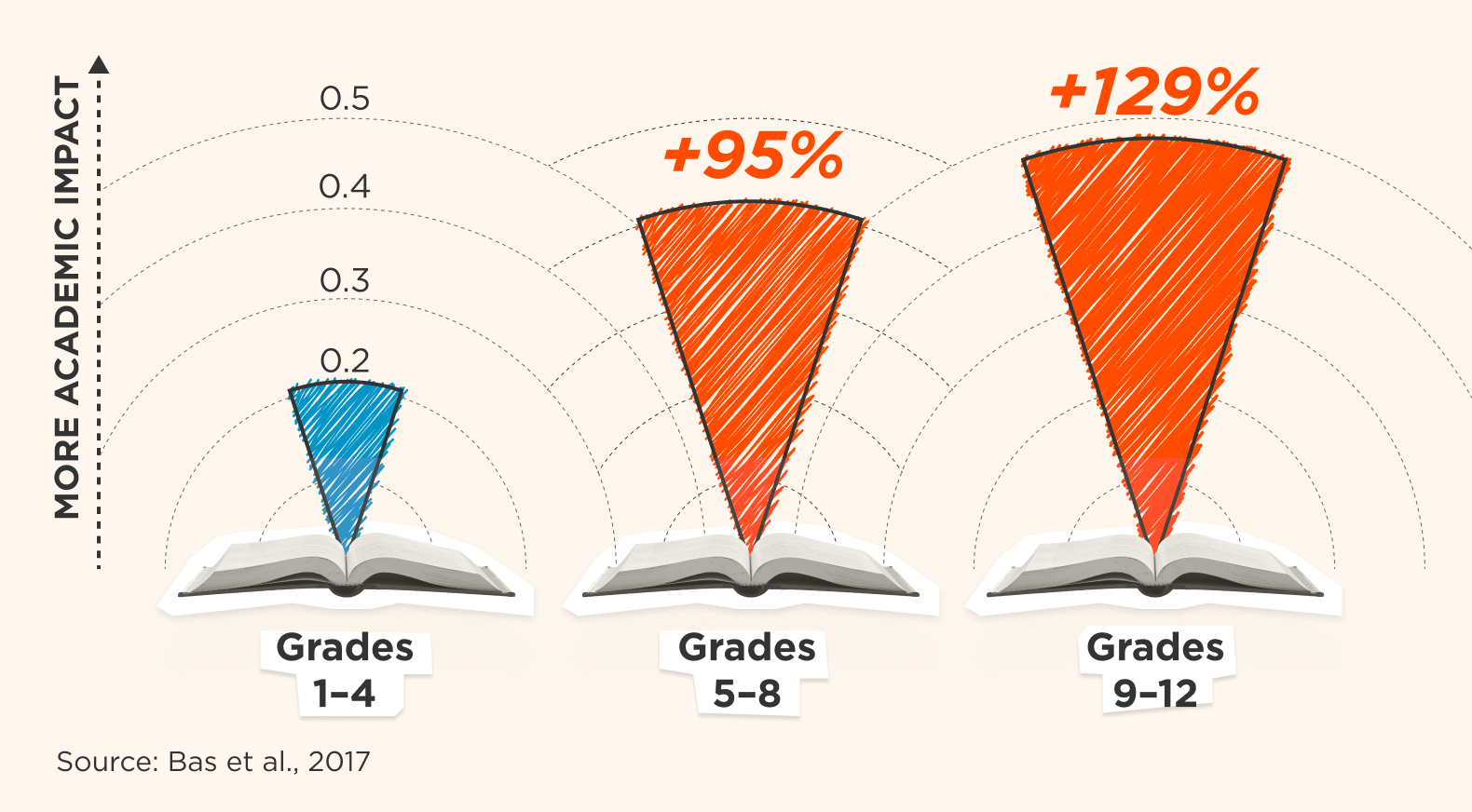

The research reveals a more complex landscape. In a 2017 meta-analysis, researchers found that while the academic impact of homework for students in grades 1–4 is indeed limited—with a small effect size of 0.21—it grows steadily through upper elementary school and into high school, rising by 95 percent for grades 5–8 and 129 percent for grades 9–12, respectively. As students mature and develop the ability to “prepare more elegant and qualified homework as their skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, cooperative learning, attention, and concentration improve,” the academic value of homework begins to take shape, the researchers say.

That doesn’t mean that all homework is high value in the later grades or pointless in the early grades—but it does warrant careful scrutiny of homework assignments. A 2023 study, for example, found that for preschool students, there were “positive links between time spent playing at home to self-regulation and, indirectly, their early prereading and math skills a year later.” A 2025 study of fourth-grade students, meanwhile, concluded that cortisol levels—a biophysical measure of stress—more than tripled when recess was cut short. For younger kids and those just starting school, then, play may do more to build both academic skills and emotional regulation than nightly worksheets.

As students reach upper elementary and middle school, the academic impact of homework becomes increasingly clear. Older students are expected to “use different resources like the internet, library, reference books, etc.” to extend their learning outside of the classroom, researchers explain in a 2017 study, helping to prepare them for college-level and professional work. While the importance of other activities and needs like sports, hobbies, and spending time with family must be accounted for, take-home work at this age also allows teachers to fill the gaps of limited classroom time: A lesson on The Handmaid’s Tale or the structure of DNA, for example, often requires students to read material at home and come to class prepared for a deeper discussion.

For Young Learners, Don’t Underestimate Context

When it comes to homework, reading and writing practice delivers better results than math drills.

Stipulated, then: The no-homework argument for the youngest learners makes sense, on the whole. But a 2022 study reveals an interesting wrinkle in that assertion, as well.

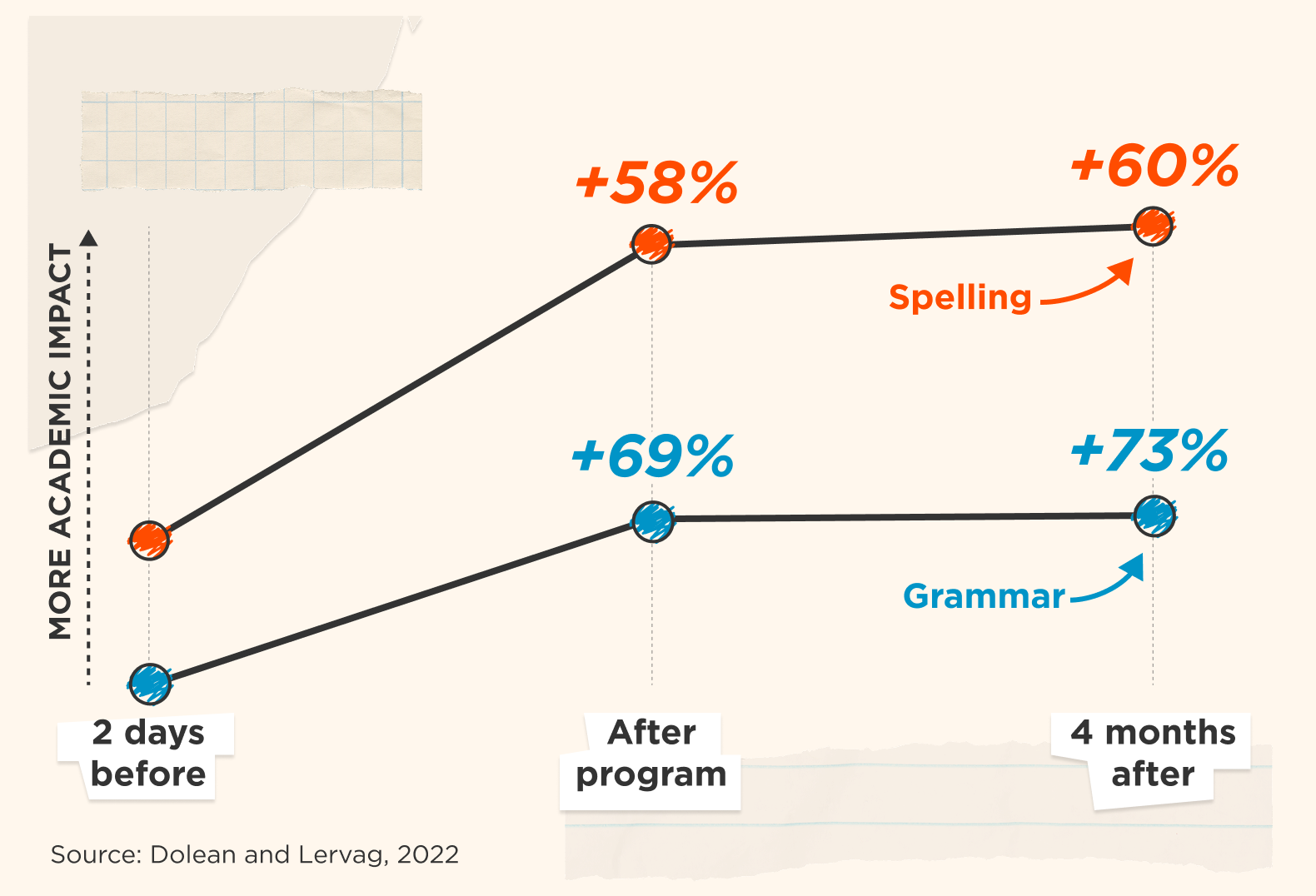

Researchers compared the math and writing homework of 440 second graders and found that students who practiced their literacy skills at home had major gains in grammar and spelling—improvements that persisted four months later. By contrast, extra math homework did little to improve outcomes beyond what students had already achieved in class.

Why was math homework less effective? Too often, it was rote work that repeated the same problems from class, the researchers say. Writing homework, on the other hand, “required students to practice the same type of problems in a different context,” they observe. For example, students may grasp that they’re, their, and there have different meanings during class, but it takes sustained practice outside of class to fluently use the words across a variety of sentences.

In early literacy in particular, the researchers assert, “some skills (such as writing skills) take time and extensive practice to be mastered, and the opportunities for practice provided by a moderate amount of homework can be beneficial to elementary students.”

The Difference High-Quality Homework Makes

Homework that extends classroom thinking improves learning and boosts engagement and study habits, too.

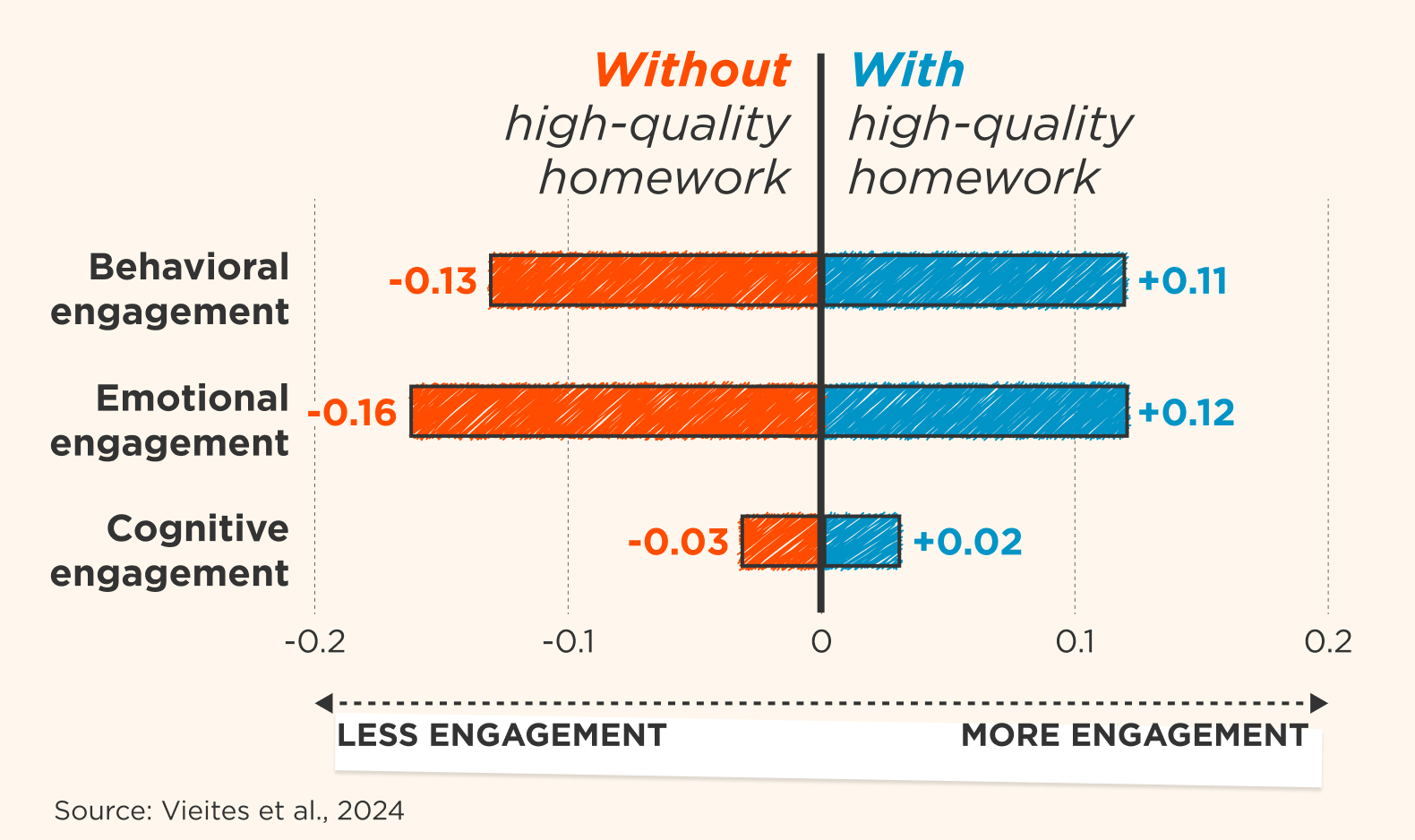

It’s not just about volume: Mandatory or reflexive homework policies, often created at the school or district level, tend to produce a lot of busywork and can waste students’ time. By middle school, low-quality homework of this kind begins to take a toll on student motivation, the research reveals, but when it’s thoughtful and well-designed—and perhaps a little less frequent—take-home work can deliver surprising outcomes.

In a 2024 study of nearly 1,000 fifth- and sixth-grade students, researchers found that high-quality homework that asked students to extend their thinking, rather than repeat what was covered in class, led to better emotional and behavioral engagement compared with rote homework tasks. In the study, teachers assigned homework that was “more elaborate” and “worthwhile” for students to complete—preparing a mini-lesson on a topic to present in class, for example, or researching and then debating a public issue—while conveying the “usefulness, interest, importance, and/or applicability of homework.” Compared with their peers in a business-as-usual classroom, whose engagement levels dropped as the year progressed, students who experienced regular, high-quality homework “showed positive emotions, were happier in school and were more interested in the classroom, paid more attention in class, and were more attentive to school rules,” the researchers found.

Thoughtfully designed homework activities can deliver an academic boost, too, without imposing a lot of new grading work on teachers. In a 2024 study, researchers asked university students to grade their own homework, comparing the “structural and conceptual differences” of their answers with an exemplar. Students scored a half-letter grade higher on their exams and also developed stronger metacognitive skills, recognizing “the value of making and correcting mistakes” as they monitored, rethought, and then revised their work.

Holding students accountable for homework doesn’t require grades or a lot of new work from teachers, either. “Student presentations and discussions are a way to check for understanding of an assignment and to let students know you expect them to attempt the problems,” says math teacher Crystal Frommert.

High-Achieving High School Students Invest in Homework Time

International data reveals a strong link between homework time and academic success, especially for older students.

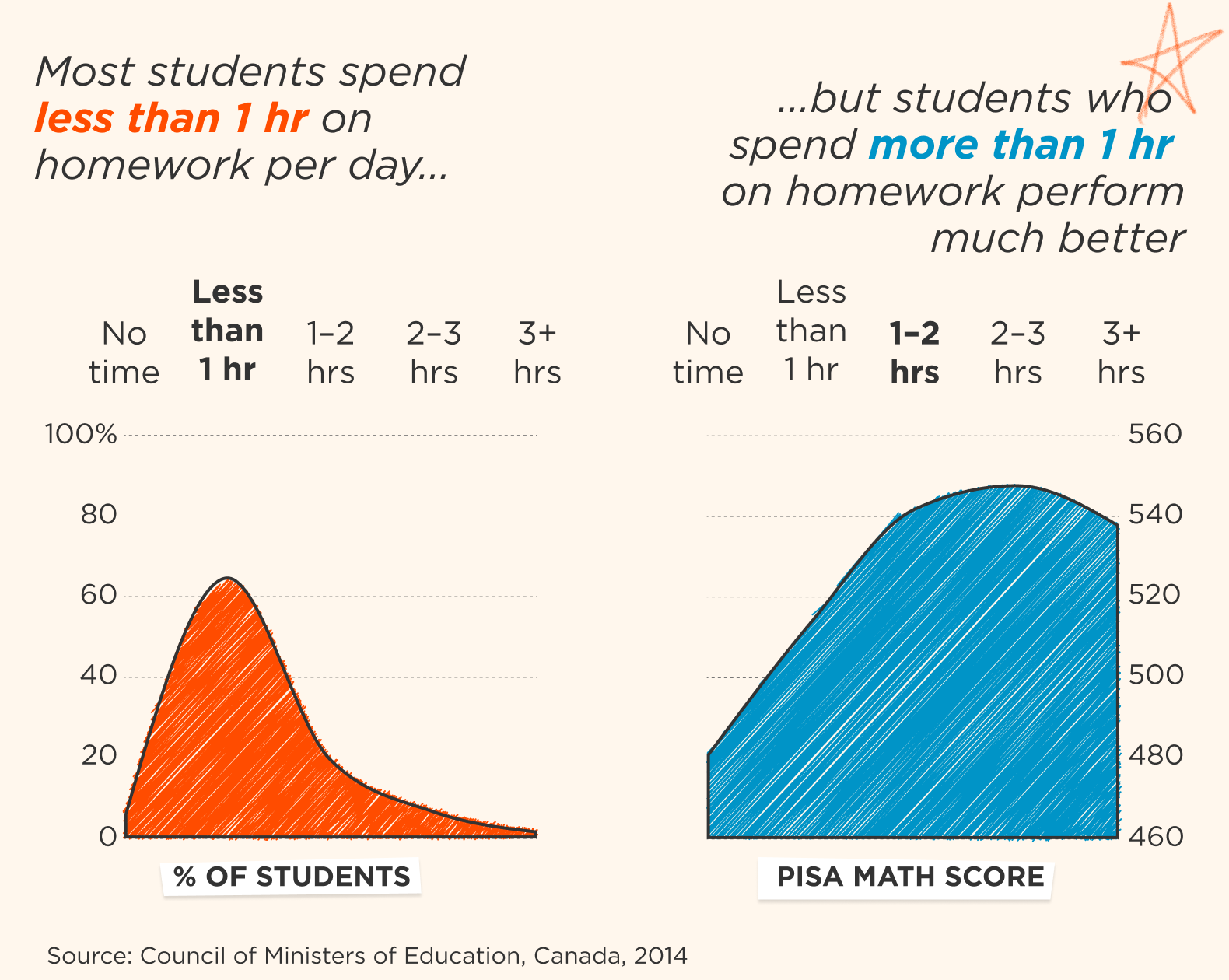

When 15-year-olds around the world took a major math exam, one factor consistently separated high scorers from low ones: the amount of time they spent each day on homework.

A 2014 analysis of global PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) scores found that high school students who spent at least an hour each day on math homework significantly outperformed their peers who did none. The difference was striking: Scores jumped from 481 to 514 with a mere hour of daily practice, then jumped again—to 542—for students putting in between one and two hours.

At the three-hour mark, however, scores increased by a meager six points, then declined after that point, suggesting that piling on excessive homework may ultimately lead to worse outcomes. The sharpest divide was between students who skip homework entirely and those who put in at least an hour, underscoring the value of consistent, moderate effort.

High school students rarely love homework, but giving them a role in designing it can help them see its value. “Students will often come up with great ideas for ways to reinforce learning at home,” writes Mike Anderson, a former teacher and current consultant. “Simply ask the question, ‘What are some ideas for how you might practice this skill at home?’ and see what they come up with.”

Being Mindful of the Real Costs of Stress

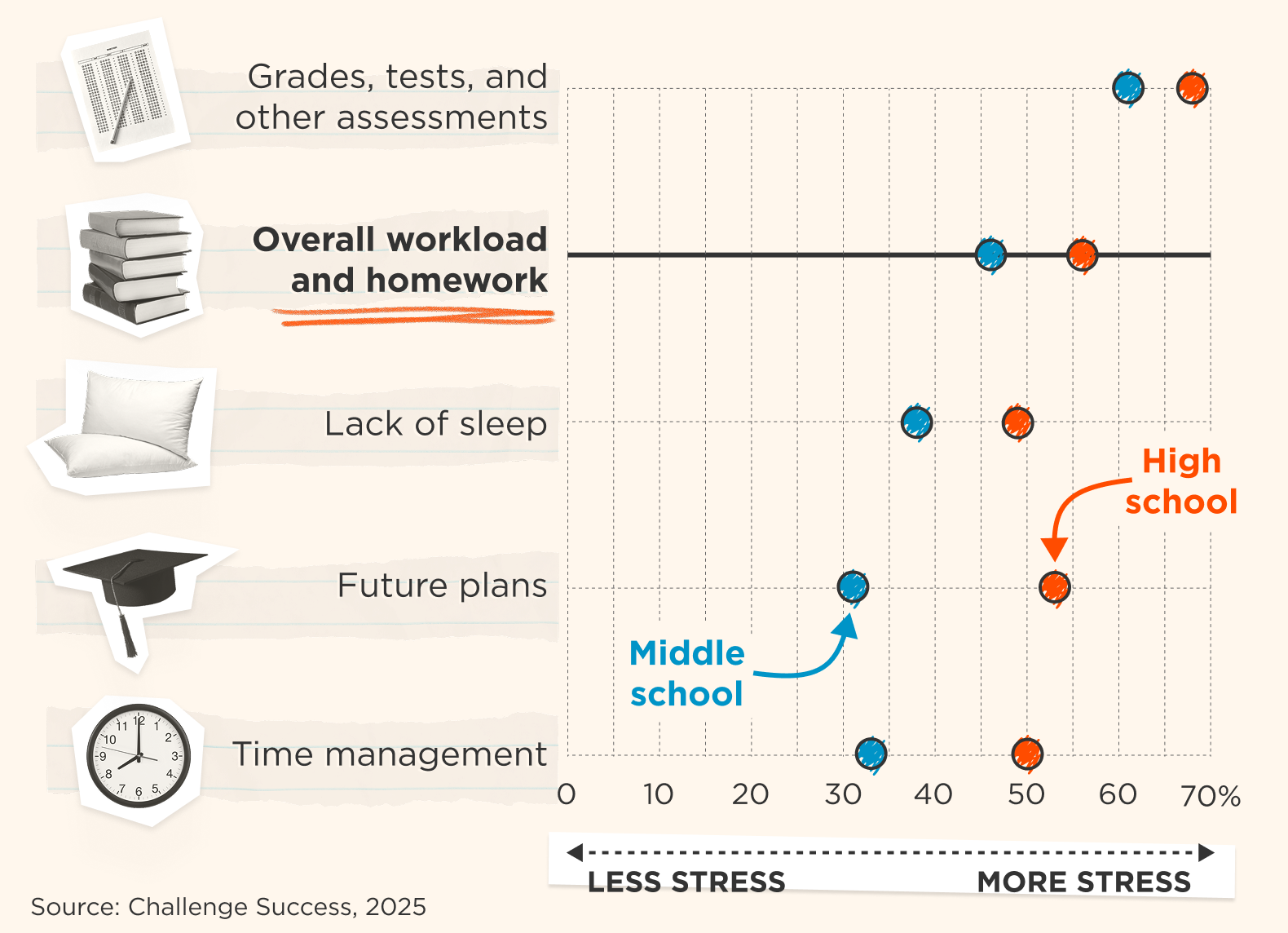

For adolescents, homework and workload rank high on stress charts—beyond concerns about late schoolwork or planning for the future.

There are costs to be borne. While homework is a game-changer academically for adolescents, the pressure of too much homework, or homework that feels purposeless, can overshadow nearly every other concern.

In a 2025 Challenge Success survey of more than 28,000 students, homework and overall workload ranked as one of the top sources of stress for middle and high school students, surpassing a dozen other sources that included time management issues, sleep, or even worries about their future. Meanwhile, more than half of those surveyed—56 percent—said at least some of their classes regularly assign homework they see as meaningless busywork.

These findings echo a 2021 report showing that “students often perceive their homework load to be excessive while not necessarily useful,” and a 2025 study that found that some “adolescents often sacrifice sleep to meet homework demands,” resulting in anxiety and depression. Schools need not give up on homework, but they might consider setting more “reasonable homework limits” to help protect adolescent sleep and mental health, they suggest.

“The minor academic benefits to assigning mandatory nightly homework simply do not outweigh the substantial drawbacks, which include potentially turning young children against school at the beginning of their academic journey,” explains second-grade teacher Jacqueline Worthley Fiorentino. It’s OK to skip a few assignments if kids are overwhelmed trying to squeeze homework between soccer practice, family dinner, and nightly reading.

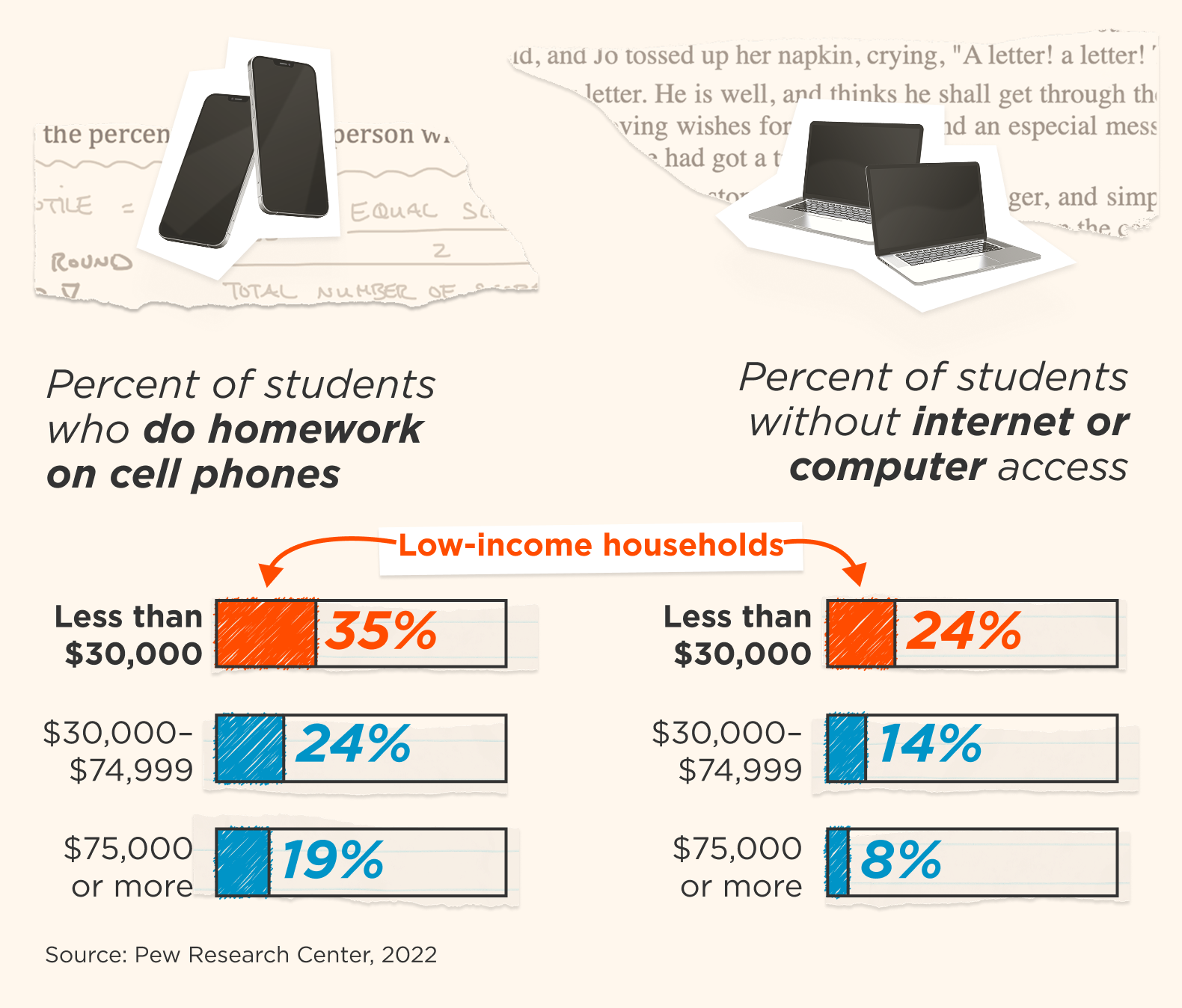

Family Income Can Increase Unfairness in Homework Assignments

About a quarter of students from families making less than $30,000 have difficulty completing their homework due to limited computer or internet access.

Many students lack the tools needed to complete homework, a point that’s often either neglected or addressed by entirely eliminating homework. Neither approach benefits kids: Ignoring the issue can leave students struggling, while no-homework policies remove valuable opportunities for practice and growth.

According to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey, more than a third of students from low-income households are cell phone–dependent for homework—about double the rate of wealthier peers. Meanwhile, only 8 percent of teens from high-income families lack computer or internet access, compared with 24 percent of teens from families under financial strain.

Another significant homework issue complicated by income and access to resources: According to a sweeping 2017 study of middle school homework, teachers often misjudge how much time take-home assignments require to complete. After analyzing the homework of over 26,000 students, researchers found that completing a theoretical “one-hour assignment” actually took anywhere from 30 to 85 minutes, with “less academically advantaged students and students with greater limitations in their home environments” struggling the most, the researchers concluded.

To remedy these problems, Victoria Thompson, a technology consultant and former teacher, recommends starting the school year with a well-crafted survey “so that teachers have the information they need from the get-go to address equity concerns in their classrooms” and adjust homework policies as needed. For example, offering a pen-and-paper assignment or creating a working group can surface possible solutions.

To get a sense of how much time homework takes to complete, and whether students have the skills to tackle it independently, educator Megan Pacheco, executive director of Challenge Success, suggests a homework audit. When time allows, set aside 10–20 minutes at the end of class for students to begin their homework. You’ll see “how long tasks actually take” and spot “hidden barriers like gaps in skills, unclear instructions, or missing prior knowledge.”

All graphics by Jan Diehm at Polygraph. Additional writing, research, editing, and design by Steve Merrill, Sarah Gonser, and Chelsea Beck.