How to Get a Whole Community on Board for School Reform

When Roger Sampson arrived as superintendent

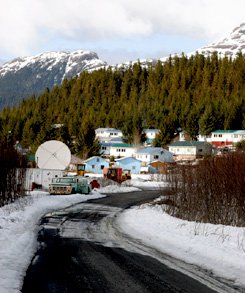

of Alaska’s Chugach School District

in 1994, he took charge of what he terms “a

mess” — a district with high teacher

turnover, hostile community relations, poor

graduation rates, and nearly zero college

attendance. “The school board was very

clear,” recalls current superintendent

Robert Crumley, who was then a head

teacher and principal. “They said regardless

of what we do, we have to change.”

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

This how-to article accompanies the feature "Northern Lights: These Schools Literally Leave No Child Behind."

Within a few years, Sampson, Crumley, and their colleagueseffected a complete transformation of the Chugach schools.They engaged the community and developed a personalized,standards-based system that has become a model for otherAlaska districts. Sampson went on to serve as state commissionerof education and early development, and was tapped tobecome president of the national Education Commission ofthe States this summer.

The Chugach educators based their approach to change onOnward to Excellence, a school-improvement process developedby the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, inPortland, Oregon. Here, Sampson and Crumley outline thekey elements of their strategy and what they learned:

Involve all stakeholders. When they started, Chugachadministrators didn't know what the outcome of the district'stransformation would be; the course was plotted with inputfrom teachers, students, parents, priests, businesspeople, andvillage elders. "I never dreamed they would come up with thedepth of comprehensiveness that they did," Sampson says."They said the bottom line was, 'When kids leave our school,we want them to have a positive self-concept, respect for eldersand other human beings, and choices for their lives -- whetherthat's living in the village or living in New York City.'"

Establish shared values. The educators and communitymembers began by agreeing on a mission and guidelines forthe process. They determined that their sole focus was the welfareof the children, and that they would take responsibilitytogether for the outcome of the change. Whenever their conversationsveered off track, a reminder of these values helpedthem focus again. "You must agree that the success will beshared and the failure will be shared," says Sampson. "As soonas it becomes finger pointing, you're dead in the water."

Identify the outcome first. It's too easy to get boggeddown in complaints and blame if you start by discussing theproblem. Sampson's advice: "Sit down with the people whoare instrumental to your communities and determine what itis you want kids to be able to do, what you want them to looklike when they're done with your system, and then workbackward, asking yourselves, "How will we know when we'rethere?" And, "What are the steps that have to happen to getthere?" "What's the role of the parent in that? The teacher?The superintendent? The board?" You will have days, weeks,months, and years to identify the obstacles to getting there -- that's not the conversation."

Build trust. Crumley recalls that the mayor of Whittierwarned him not to hold community meetings -- relationsbetween the residents and schools were too strained. Using food,door prizes, and student performances to entice residents toattend, however, the district held ten meetings during the first eighteenmonths and convinced the community they were true partnersin the process.

"The key was to act on the input and make it explicit bytelling them what action you've taken," Crumley says. Forinstance, community members said they worried about kidsbeing impolite and disrespectful toward elders. The districtadded character education to its student-performance standardsand made sure residents knew their wishes had becomeschool policy.

Change everything at once. In those first few years,Sampson overhauled everything: the Chugach budget, curriculum,policy, staff-development practices, and instructionand assessment methods. "Here's why reform fails inAmerica," he says. "When you hear about success stories, theyusually involve some change in curriculum or instructionaldelivery style, but it usually doesn't bring with it all the otherkey components to make it replicable and survivable. If youdon't have those other pieces, you're putting the roof onbefore the walls go up; the roof will stay on for a minute,until something shakes. Then it falls."