Is Your School Asking the Right Questions About Poverty?

Leading underachieving students in poverty to success involves asking the right questions, finding the leverage points, deploying resources effectively, optimizing time, and sharing data effectively.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Editor's note: This piece was adapted from Turning High-Poverty Schools into High-Performing Schools by William H. Parrett and Kathleen M. Budge.

Devon dropped out of school at age 13. No one knows where he is today. Most likely, he's not in school. Devon was going to be retained to spend another year in the sixth grade as a 13-year-old. He was embarrassed and felt alone. He didn't want to be with a new group of kids who were younger. Truth was, Devon had been passed along with low reading skills for years. Now, in the beginning of his adolescent years, he was told he was going back. He gave the class a try for three weeks and then disappeared. With good intentions, Devon's teachers had recommended an intervention -- retention -- that resulted in the opposite effect of what they had hoped.

Retention as an intervention for underachievement does not work. Sixty years of research bear out this conclusion. Thus, we view it as the poster child for the many entrenched mindsets, policies, structures, and practices that are commonly employed in schools to “allow a student to catch up” and, at times, as a punishment for not keeping up.

High-performing, high-poverty schools endeavor to build leadership capacity to better meet the needs of students like Devon. As part of committing to that work, leaders aggressively confront entrenched, counterproductive strategies and beliefs. They are relentless in this effort. They know that inaction perpetuates low achievement and undermines other effective practices. But where do they begin?

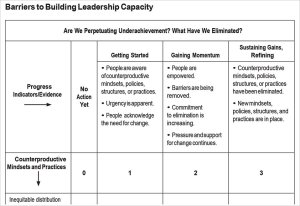

To guide learning and to help in reflecting on the current situation in your school, use the "Are We Perpetuating Underachievement? What Have We Eliminated?" rubric (click image to download), which isolates seven specific mind-sets, policies, structures, and practices that high-performing, high-poverty schools have helped to identify as barriers to building leadership capacity and improving achievement.

Asking the Right Questions and Finding the Leverage Points

Because high-performing, high-poverty schools are places of reflection and inquiry, leaders' work in these schools is better characterized in the form of questions than in formulaic lists of strategies. If a school's primary goal is to significantly improve achievement, particularly of low-income children, these questions should provide valuable, insightful direction:

- Are we deploying financial, material, and human resources effectively?

- Are we optimizing time, extending it for underachieving students, and reorganizing it to better support professional learning?

- Do we have a data system that works for classroom and school leaders?

Are We Deploying Resources Effectively?

Principals in high-performing, high-poverty schools ensure that the necessary financial, material, and human resources are available for students and adults to succeed (Ball, 2001; Leader, 2010). Leaders in the schools that we studied began their remarkable turnarounds by making tough calls -- and many of those decisions were about how to use resources. They not only used the school's existing resources innovatively, but also often secured additional funding from the district office and capitalized on relationships with external stakeholders to garner support for the school.

Approximately 70 to 80% of a typical school's budget is dedicated to personnel, so it stands to reason that recruitment and retention of talented staff is a top resource-management priority. When decision making about resources, chiefly personnel, is decentralized to the school level, the principal and other site-based leaders can further their improvement efforts by hiring teachers and staff with qualifications that match the school’s needs.

In tough economic times, effective resource management becomes increasingly important. Principals sustain the school's success by working collaboratively with staff to stay focused on the priorities that guide their work. They know that cuts in critical resources can jeopardize their hard-won gains. Countering these challenges becomes their top leadership priority -- particularly as they work to recruit and retain talented staff.

Are We Optimizing Time?

The manner in which time is used is closely linked to retention of high-quality staff. All students are likely to benefit from improving the quality of academic learning time, and those who live in poverty may require additional high-quality time. Teachers also need time to learn, especially when they're learning collaboratively with others. Teacher learning and student learning are two sides of the same coin. When teachers are afforded time to learn collaboratively, they can in turn optimize academic learning time within the school day and best plan for student learning outside the school day.

Extending academic learning time can occur in at least two ways -- literally extending the available time for students to learn, or better using the time within the traditional school day. High-performing, high-poverty schools do both. Underachieving students living in poverty often require more instructional time to catch up to their higher-achieving peers. Schools can offer a blend of before- and after-school tutoring, weekend and vacation catch-up sessions, summer school, full-day kindergarten, and sheltered classroom support.

Summer instruction in particular may be as important as any extended time intervention, as it serves to maintain continuous learning, counters the loss of achievement gains caused by long gaps in school, and provides needed nutrition and other auxiliary supports (Borman & Dowling , 2006).

Do We Have a Data System That Works for Classroom and School Leaders?

Effectively managing resources (money, people, time) requires accurate information. All schools in our study implemented data systems to guide their decision making. In fact, using data-based decision making was one of the two most common explanations offered for the schools' success (the other was fostering caring relationships).

Constructing and implementing a data system is an essential function that moves a school toward addressing the underachievement of students living in poverty. In HP/HP schools, leaders facilitate an ongoing, courageous look in the mirror. These schools have access to accurate, timely data that allow school and classroom leaders to set goals and benchmarks, monitor progress, make midcourse corrections, and perhaps most important, design and successfully implement needs-driven instruction and interventions.

Victoria Bernhardt (2005), a nationally respected authority on data use in schools, suggests four different types of data that should be accessible:

- Data related to student learning (for example, classroom-based assessments, standardized test data, teacher observations)

- Data related to perceptions held by stakeholders about the learning environment, as well as values, beliefs, and attitudes

- Data related to school and student demographics (for example, attendance, graduation rate, race/ethnicity, class, gender, level of teaching experience, level of teachers' education)

- Data related to structures, processes, programs, and policies (for example, after-school tutoring programs, RTI Tier 2 intervention programs, summer schools)

Action Advice

- Consider your school's budget. Do you consider your budget a moral document? Does it reflect your values, goals, and priorities as a school?

- Evaluate your current hiring practices. Do they result in hiring personnel who match the needs of your school?

- Take action to retain talented personnel. Have you taken stock of the ways in which your school encourages talented people to stay?

- Hold high expectations. Have you evaluated current practices ensuring that all teachers hold high expectations for their students and themselves?

- Provide extended learning time. Have you explored ways to extend learning time for underachieving students?

- Analyze your school calendar. Is it learning centered and focused on the needs of underachieving students?

- Provide time for professional learning. Have you reorganized the schedule and calendar to provide job-embedded professional learning opportunities?

- Analyze the way decisions are made. Are multiple forms of data used to make instructional decisions in the classroom and systemic decisions schoolwide?

- Conduct an equity audit. Have you assessed how equitably your school is meeting all students' needs?

We encourage you to share any questions or additional action advice you may have found for turning high-poverty schools into high-performing ones.