Teaching Tone to Deepen Reading Comprehension

Explicit instruction in how tone is conveyed in writing helps students become more thoughtful readers and more precise, empathetic writers.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In a world of text messages, Snaps, and Discord chats, the power of the written word, albeit brief, remains as a prevalent source of communication. But in the world my students inhabit behind keyboards, I have noticed a weakening ability in them to read between the lines.

To address these gaps, I begin with teaching tone. Over time, I’ve found that when tone is taught intentionally and visibly, students become more thoughtful readers and more precise, empathetic writers. Tone is not a vocabulary problem, it’s a thinking problem. Here is how I approach tone instruction and help students move beyond surface-level comprehension.

Students Already Interpret Tone—They Just Don’t Name It

Before students can analyze tone in literature, they need to recognize that they already interpret tone constantly, in texts, messages, and everyday interactions.

I start by asking students to read the following text exchange between two friends, Jordan and Taylor:

Jordan: Hey, what’s up? You still coming over?

Taylor: Maybe, IDK yet.

Jordan: OK, let me know. I cleaned up and everything.

Taylor: Nice.

Now, the tone of the messages can change how you understand the conversation. How does this sound if the participants are annoyed? Tired? Playful? How do those tones change the meaning of the messages? Here are analysis questions I ask my students:

- What are two possible tones for Taylor’s responses?

- How does the tone you choose for Taylor affect how you understand their mood or attitude toward Jordan?

- If Taylor was excited to come over, how would you read their texts differently?

- If Taylor was feeling annoyed or uninterested, how does that change your understanding of their relationship with Jordan?

When students are invited to consider how tone alters interpretation in familiar contexts, they begin to understand that tone is not just about what is said, but about how it is said, and how it is received. This realization creates an accessible foundation for literary analysis.

Tone Must Be Explicitly Taught

One of the most common misconceptions in literacy instruction is that students will “pick up” tone naturally as they read more. In reality, tone requires explicit tools. Students need to be taught what to look for and how to justify their interpretations. These tools include:

- Diction

- Syntax

- Context

- Connotation

- Figurative and literal language

- Imagery

Explicit instruction transforms tone from an abstract concept into a set of observable clues embedded in the text. As a class, we discuss how we can use all of these tools to determine the intended meaning of the speaker.

Context Is the Lens That Shapes Meaning

Words do not exist in isolation. The same phrase can communicate vastly different meanings depending on the situation, speaker, and audience. As a class, we discuss whether the intended meaning matches the interpretation.

Context is key! In order to help students experiment with how tone shifts across contexts, I have students work through an activity with partners. The response to each of the following sentences is “Really?” but the objective is to change the tone of that word to change their intended meaning.

- I just won us tickets to the concert tonight!

- I can run a marathon without any training.

- I accidentally spilled coffee on your laptop.

- I read that dolphins can recognize themselves in a mirror.

This work is especially important for developing readers or English language learner students, who may default to literal interpretations.

Making Tone Visible Supports Deeper Thinking

Associating tone with color is one of my most effective approaches. When students assign colors to tonal shifts in a text, they are forced to slow down, reread, and justify their choices.

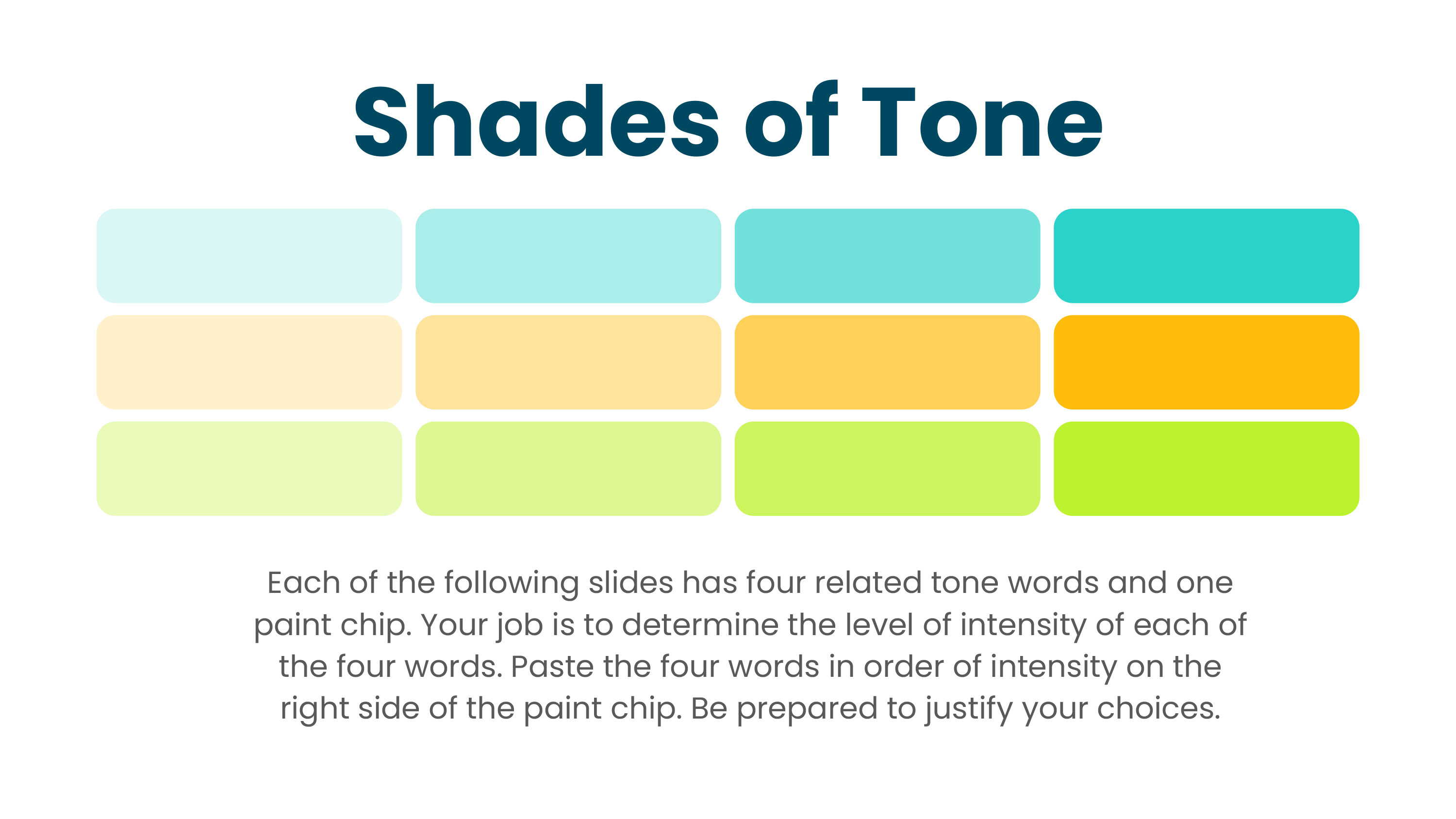

To help students visualize tonal intensity, I use a color-association activity called “Shades of Tone,” adapted from work by educator Sari Arfin Schulman. In this modified version, students examine groups of related tone words and determine their relative intensity using a shared color palette. Their job is to determine the level of intensity of each of the four words. As they justify their choices, students engage in rich discussions about connotation and nuance while expanding their vocabulary.

Color-coding tone externalizes internal thinking, encourages discussion around connotation and intensity, helps students see tonal shifts across a passage, and creates a visual map of meaning.

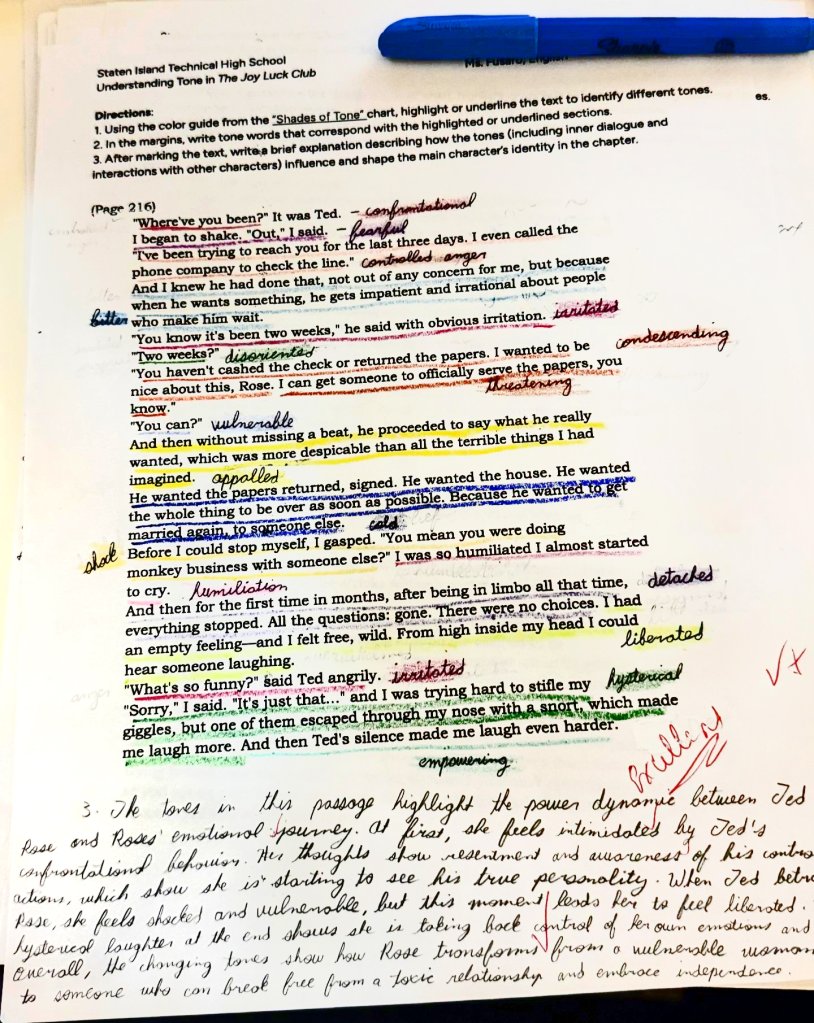

Using the guide of color as tone, students are given a different excerpt where they must “color it up” and write tone words in the margins. Rather than highlighting randomly, students must make deliberate decisions about how language feels and why. This process transforms annotation from a compliance task into a meaningful analytical tool. Quality guided annotations lead to better writing, because students are building from a visible record of their thinking.

Once they finish coloring and annotating, I ask students to write a brief explanation describing how the tones (including inner dialogue and interactions with other characters) influence and shape the main character’s identity in the chapter.

Why Teaching Tone Matters

Teaching tone is a critical thinking skill our students desperately need in a world dominated by abbreviated communication and constant digital noise. When students learn to slow down and examine how something is said, they begin to read and, subsequently, write, with empathy, precision, and depth.

Most important, the work doesn’t end with naming a tone word. Students apply their analysis to explain how tone shapes character, conflict, and theme, which is a direct bridge to higher-level analytical writing. Their color-coded annotations become a road map for thinking, helping them craft clearer, more insightful interpretations.