A Simple Visual Routine to Help Students Engage With Poetry

Teachers can have students create comics based on poems to better understand their themes and spark meaningful conversation.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.When students dig into a poem for the first time, they don’t always recognize the playfulness that poets use in their language, making it harder for students to get excited about what they are reading. But by using a simple visualization routine, teachers can help their students approach poetry with a sense of play and wonder, while also inviting them to slow down and notice the details that the poet employs. In my classroom, one of my poetry visual routines of choice is the four-frame comic.

THE FOUR-FRAME COMIC ROUTINE

Each year, my students keep paper writer’s notebooks to capture quick thinking and low-stakes writing. I introduced these notebooks after learning how drawing can be a powerful tool for learning across disciplines.

In this particular routine, students create quick, simple comic strips related to the poetry they read. This draws students’ attention to what they can or cannot yet visualize in the poem and how the images they can represent form patterns in the poem. Four-frame comics invite keen attention and divergent thinking, and they identify early interpretations or misinterpretations of the poem.

CONNECTING WITH COMPLEX POETRY THROUGH VISUALS

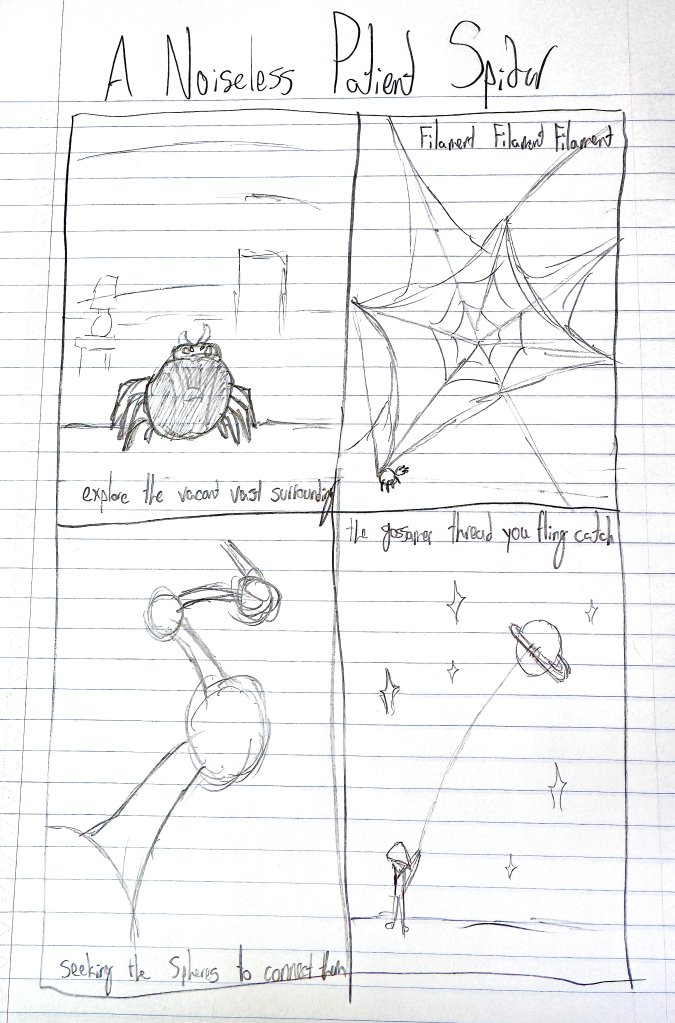

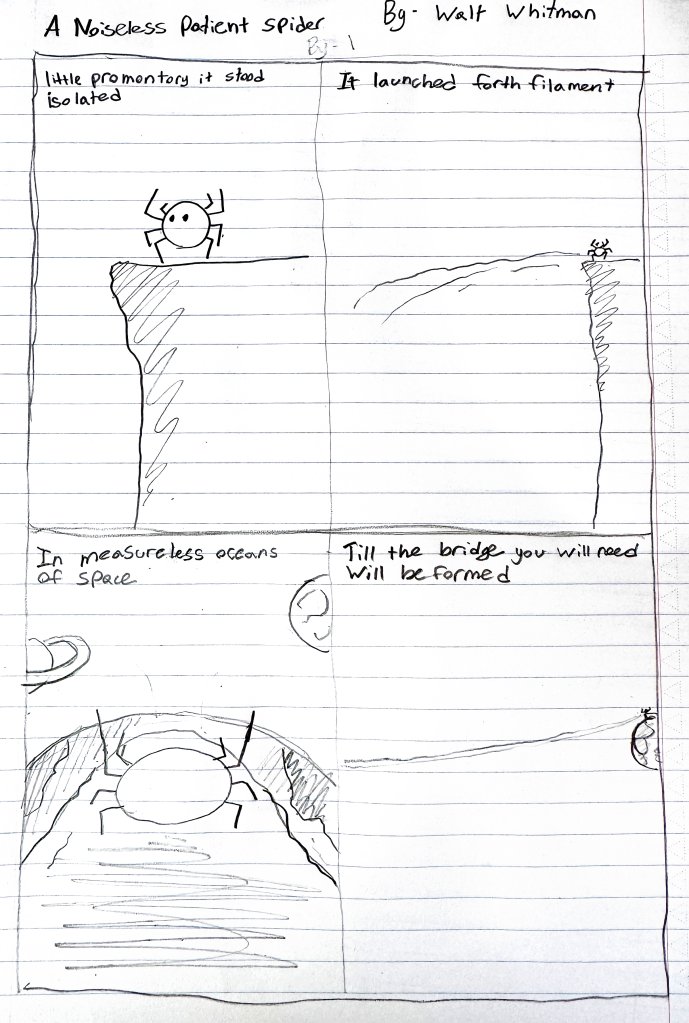

Walt Whitman’s “A Noiseless Patient Spider” is a classic poem that shows up in many high school English classes. It draws readers into a spider’s desperate attempt at connection as it casts “filament, filament, filament” hoping to build a bridge. The poem is ultimately about our human craving for connection, as the last line emphasizes.

For high school students, it is a challenging poem, but one that blends the familiar image of a spider with unfamiliar language like “filament” and “gossamer.” The poem could be frustrating to study, but with the right approach, it can be incredibly relatable.

Here are the four steps I use to spark conversation using comics:

1. Create the comic. After we define some of the trickiest vocabulary in the poem and read it a second time, I present my students with a challenge before we discuss it any further. “Find the four most important images in this poem. Sketch them into a tiny comic strip on a page in your notebook, copying the lines of the poem into each frame of your comic.”

Here are what two high school students created with this challenge in about five to seven minutes of class time.

2. Gallery walk. Once all students have completed their comics, I ask students to leave their notebooks open as the entire class engages in a gallery walk, looking at one another’s work. I give students two small sticky notes to leave notes with observations or questions on their peers’ work.

3. Turn and talk. After returning to their seats, students turn and talk to a partner briefly about why they chose the images they did and why each frame is critical to understanding an important meaning in the poem.

4. Whole class discussion. Finally, we come back together as a whole class to talk about variations in what students spotlighted in their comics and to discuss the various themes of the poem.

The above process gets every student reading, writing, speaking, and listening about the poem at hand. Not only does the four-frame comic routine help students understand that poetry conjures images in our minds, but also it helps them make meaning out of what they read and see the value in what a poet has produced.

In an age when artificial intelligence could spit out a reasonable interpretation of Whitman’s masterpiece, engaging the students in zero thinking, there is something beautiful about hearing the scratch of pencils on paper, the buzz of conversation, and the interpretive epiphanies students feel proud of, especially in a poem that may have felt like navigating through fog on a first read.

USING THE FOUR-FRAME ROUTINE IN DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

This routine doesn’t only work with classic poems; you can also use it with contemporary works and even long poems. When reading longer poems, keeping the limit at four frames leads to conversation about which four images earned the right to be included and what made them most important. You can even use this routine as a first step in prewriting a short, analytical essay about a poem.

The four-frame comic can become a springboard for writing in other genres as well. A ninth-grade student of mine, featured in my book Poetry Pauses: Teaching With Poems to Elevate Student Writing in All Genres, responded to a prompt to create a comic with only images based on Charles Simic’s poem “Wooden Church.”

Next, since we were in a personal narrative writing unit, I asked him to create a four-frame comic based on his story that he planned to write—about a break-in at his house—including the four images he most wanted readers to remember from his story.

Taking time to slow down and think through how images create impact for us as both readers and writers is a valuable step toward crafting a vivid personal narrative that others will want to read.

Finally, we can even introduce our students to a whole new genre of creative writing. “Poetry comics” is a genre term coined by Grant Snider and one he celebrates during #poetrycomicsmonth on social media each November.

My students always enjoy reading Snider’s thought-provoking and whimsical poetry comics from his blog, Incidental Comics, and we can use them as mentor texts to create poems that are already comics by design. This elevates our students’ sketches from interpretive tools to expressive ones, while reiterating the importance of visualization as a component of both reading and writing.

Even for students who are far from artists, inviting them to create quick, four-frame comics helps them to visualize, analyze, and evaluate the importance of imagery in their reading and their writing.