A Research-Backed Tool Kit of What Works—and Doesn’t Work—in Education

A large-scale analysis of over 2,500 studies separates the wheat from the chaff, highlighting what works, and what’s suspect, in the field of education.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Education fads come and go, but how do they stack up against the more modest, everyday pedagogies that make up the bulk of a teacher’s repertoire?

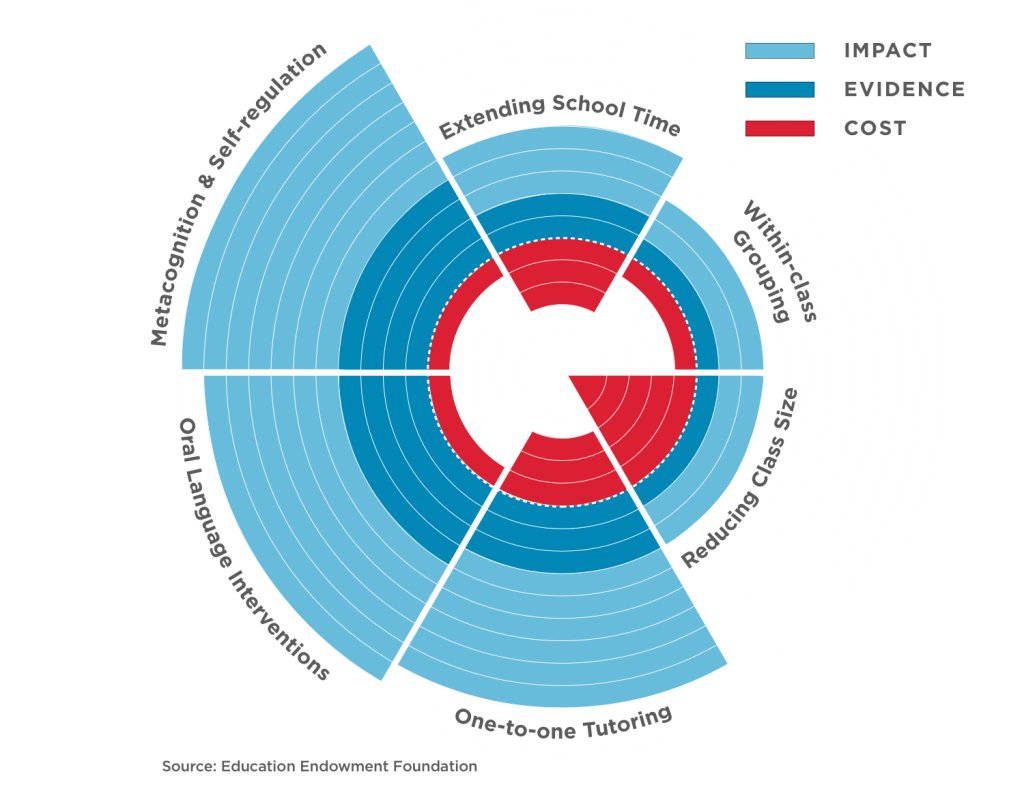

Recently, the Education Endowment Foundation, a U.K.-based nonprofit, published the Teaching and Learning Toolkit, a high-quality compendium of 30 common educational strategies or structural changes, ranging from metacognition to one-on-one tutoring to extending the school day. For each strategy, experts sifted through the research—in most cases evaluating hundreds of studies—to calculate the academic impact (the number of additional months of academic progress made), the evidence (how robust the empirical evidence is), and the cost of each strategy.

Recently highlighted in the seminal research journal Nature, the tool kit of pedagogies is used by more than 70 percent of secondary school leaders in the U.K. to make informed decisions about the best, most cost-effective programs and strategies to adopt.

There are no silver bullets in education—what works for one group of students may not work for another. But here are four powerful strategies every teacher should know about, plus a few that either deserve closer scrutiny or should be jettisoned.

WHAT WORKS

Topping the list were interventions that could easily be implemented in classrooms without having to purchase costly programs, make significant staffing changes, or alter the structure of the school day. These interventions required only a modest investment in teacher training—much of which could be accomplished informally through a school’s professional learning community.

Metacognition and self-regulation. The strategy that received the highest score for academic impact, metacognition and self-regulation involves teaching students how to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning—helping them build awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses while gaining a deeper understanding of which learning strategies are best suited to a given task.

To maximize the benefits of metacognitive strategies, teachers should model their own thought processes, the tool kit suggests—for example, they can explain their thinking when reading a text or solving a problem. Teachers can also encourage students to ask themselves questions like “What did I find difficult about this lesson?” and “What can I do if I get stuck on a problem?” to help surface gaps in their understanding and make good use of educational resources.

You can also quiz students about their plans to study for an upcoming test; ask them to discuss, evaluate, and test ideas and methods that are different from their own; and share tools and strategies to help them assess their own learning.

Reading comprehension strategies. While the conversation around reading instruction has recently focused on phonics and decoding, it’s also critical that students across all age groups learn active reading strategies such as inferring meaning from context, summarizing key points, using graphic organizers, and actively interrogating texts by asking and answering questions as they read.

The researchers concluded that these strategies have “very high impact for very low cost based on extensive evidence”: Reading comprehension activities advance student learning by an average of six months, making it “a crucial component of early reading instruction,” according to the tool kit.

Before jumping into a difficult text, for example, teachers in Edutopia’s community sometimes develop a “comprehension canopy” with students, identifying the main purpose, asking an overarching question, and previewing the background knowledge they’ll need to keep pace with the material. To deepen reading comprehension further, students can use thinking strategies such as connecting ideas or making predictions, or they can create their own visual annotations to pose questions and synthesize information.

Oral language interventions. One of the most effective methods to reinforce learning is to explicitly use structured questioning techniques and discussions to encourage students to articulate what they know. Activities include reading books aloud, having conversations about a topic, going over vocabulary lists and concepts, and asking questions that help students delve more deeply into a topic.

At School 21 in London, where oracy is valued as much as reading and writing, teachers use a range of strategies—from Talk Detectives, where students use a checklist to spot key elements in classroom discussions, to a practice called Ignites, which allows students to practice their public speaking skills in front of an audience. After analyzing 154 studies, the researchers concluded that oral language interventions are a low-cost, evidence-backed strategy that boosts learning by an average of six months.

Collaborative learning. Asking students to work together in small groups has “a positive impact, on average, and may be a cost-effective approach for raising attainment,” according to the researchers. Avoid unstructured group work, however—teachers are encouraged to step in and carefully design activities that are challenging and robust enough to exceed the capabilities of a single student. “The most promising collaborative learning approaches tend to have group sizes between 3 and 5 pupils and have a shared outcome or goal,” according to the tool kit.

One highly effective collaborative learning approach is the jigsaw method, but it needs to be carefully constructed: Students are assigned a topic and then form small groups to first specialize, then consolidate and share knowledge with their peers.

WHAT’S QUESTIONABLE

For school leaders, it’s never just a question of what works. After all, working within the constraints of a limited budget—and limited staffing resources—requires a judicious approach. In a 2016 study, Harvard researchers explained that when it comes to meeting the needs of students, “budget decisions serve as a compass.” Questions about cost, required teacher training, and the impact of new programs on the health and well-being of teachers represent key dimensions that are often overlooked when evaluating the research on effective education practices.

Extending school time. Increasing the time that students spend on academics during school does improve outcomes—a modest increase of three months’ worth of additional learning over the course of a school year—but it can spread teachers thin, dramatically increasing workloads and potentially harming their well-being.

There’s also a significant opportunity cost: Increasing academic seat time can crowd out time spent on professional development, lesson planning, and other crucial tasks, lowering the overall quality of teaching. Instead of extending school time, resources are better spent on well-structured, high-quality after-school programs, the report concludes.

One-on-one tutoring. Pairing a student with a tutor adds roughly five months’ worth of learning, on average, making it seem like a highly effective strategy—albeit with notable caveats. The approach is expensive, especially when delivered by teachers, and the research is riddled with studies that lacked independent, third-party oversight, calling into question the effectiveness of the strategy.

Instead, two similar strategies should be used: small-group tutoring and peer tutoring, both of which yield nearly similar academic results at a fraction of the cost. In the classroom, peer tutoring may even be preferable, since “learners take on responsibility for aspects of teaching and for evaluating their success”—giving them the metacognitive boost that deepens learning.

Peer tutoring is highly effective when “used to review or consolidate learning, rather than introducing new material,” the tool kit suggests. Use rubrics to guide peer feedback and ensure that it remains productive. Finally, one of the best ways to learn about a topic is for a student to take responsibility and teach it to someone else.

WHAT DOESN’T WORK

The tool kit doesn’t shy away from challenging assumptions we have about what works—through a systematic analysis of the research, it identifies strategies that at minimum deserve more scrutiny, if not a wholesale rejection by schools.

Repeating a year. Two million children are retained in the U.S. each year at an estimated cost of $20 billion—yet it’s a “significant risk” that few ever recover from, the report found, resulting in a host of problems, from low self-esteem and apathy toward school to lower graduation rates. On average, these students lose three months of academic progress compared with their peers who move on, even after completing an additional year of schooling.

Learning styles. Despite a decades-long campaign to axe learning styles from schools, 89 percent of teachers still believe that matching instruction to a perceived learning style—visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic—improves learning.

Every student learns in different ways, but sensory systems work together—not independently—when information is being processed, and the research shows that labels like “visual thinker” can discourage students from exploring other ways of thinking about an idea. Instead, use a multimodal approach: Ask students to use a variety of methods, from drawing to acting concepts out to writing songs, to learn about a topic—the research shows that it’ll lead to more durable, robust learning.