Prioritizing Active Learning Experiences

This guide to strategies for setting up engaging, collaborative learning activities should be especially helpful to new teachers.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.I remember taking notes, reading textbooks, and completing worksheets when I was in school, and when I began teaching, I wanted to create a more engaging experience for my students. I found that those sit-and-get-style lessons I grew up with could easily become more active learning experiences by incorporating a few different strategies. If you’re hoping to increase student interaction, engagement, and participation but feel limited to traditional practices of direct instruction, here are some methods you can try.

Turn a Lecture Into Student-Led Learning

Lecturing, though fairly common at the secondary level, may not offer students an opportunity for meaningful engagement with the material or one another. The following replacement ideas can position students as active learners rather than simply good listeners.

Try station rotation: Break your lecture material into chunks, and designate places around the classroom or hallway for students to learn about each part. Stations should contain instructions and necessary materials. Divide students into teams equal to the number of stations, then set a timer for how long groups will spend at each location. For example, rather than lecturing on sensory systems, I have psychology students move to different stations around the classroom to learn and practice concepts related to vision, hearing, and other senses.

Consider inquiry-based lessons: An inquiry-based lesson presents students with a question to be answered. Start by identifying the lesson’s goal or theme, and turn it into a broad question. For example, instead of lecturing about the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, I framed the lesson around the question, “What motivated Japan to attack Pearl Harbor?”

After determining the question, scaffold students toward finding the answer by providing the steps and resources. In this example, small teams received four sets of documents in envelopes, each representing a different factor motivating the attack: photographs, newspaper clippings, historian accounts, and maps. Teams worked through each envelope to investigate each of the four causes.

Incorporate a jigsaw: In a jigsaw, students become teachers. Divide a lecture into no more than six main topics. Place the class in small groups, the same size as the number of topics. Each group member will be responsible for one of the topics, assigned or chosen. Provide guidelines for gathering information, and set a clear time frame.

Students then report their findings to their teams. For extra support, have students meet with classmates studying the same topic before teaching it to their teams, allowing time to clarify misunderstandings and gather details. So instead of lecturing on Cold War events of tension, I used the jigsaw method, assigning each team member a different hot spot to become an expert on and explain to their small team.

Reimagine Readings

Like the lecture, reading can be a one-way stream of information, with little room for students to interact with the material or with others. Here are a few strategies that helped me turn classroom readings into active and cooperative activities.

Set up doc walks: A doc walk, or a document walk, is a variation of the gallery walk. In a doc walk, short readings are posted around the classroom and hallways. Students carry a clipboard and handout with them as they read and respond to the short passages at each stop. For example, instead of having students silently read about the U.S. government’s motivation for settling the Great Plains, I set up a doc walk with short readings and pictures throughout the hallway.

Put together grab-and-goes: A grab-and-go activity breaks a large reading into smaller sections placed in bags (or boxes) with related images and photographs. Each bag is labeled and corresponds to questions on an activity handout. Students can work in small groups or individually, depending on the number of bags available.

Timed reading sessions (five to eight minutes, but no more than 10) ensure that students fully explore each bag’s resources before grabbing a new one. Instead of having students silently read about the American experience during World War II, I used a grab-and-go system. Each bag represented a different people group and their experience during the war.

Try read-and-rolls: This reading strategy involves students rolling a die to determine how to process a text. For example, rolling a one might mean drawing a picture of what they’ve read, while rolling a two might involve writing a haiku summarizing the main point. I usually split a reading into sections, so students will read and roll multiple times throughout the text.

In psychology, my students read about split-brain research. I divide the reading into five sections, and at the end of each section, students roll for a task to complete. The read-and-roll strategy adds structured unpredictability, interaction, and engagement to a traditional reading task.

Transform Worksheets Into Tactile Activities

After students acquire foundational skills, teachers often have them synthesize and practice. From my experience, this was typically in the form of printed worksheets. Here are ways to move these skills from pencil and paper to tactile, team-based activities.

Create collaborative graphic organizers: Graphic organizers help students process information using formats like T-charts, Venn diagrams, and webs. Instead of sorting information on paper, students can contribute to collaborative diagrams either in a collective classroom space with responses on sticky notes or on their tabletops by sorting physical cards. For example, when my psychology students learned about the endocrine and nervous systems, rather than completing a compare-and-contrast worksheet, pairs sorted fact cards into a Venn diagram drawn on their desks with dry-erase markers.

Try toy box displays: Instead of defining and applying vocabulary words on a worksheet, students can practice concept identification and application by building with toys. Using a collection of toys and figurines, students can demonstrate the meaning of different concepts by setting up toy displays.

For example, I asked my psychology students to demonstrate group behavior concepts using toys on their tabletops. Teams built displays, took pictures, and shared them with the class, explaining how their displays demonstrated the assigned concepts.

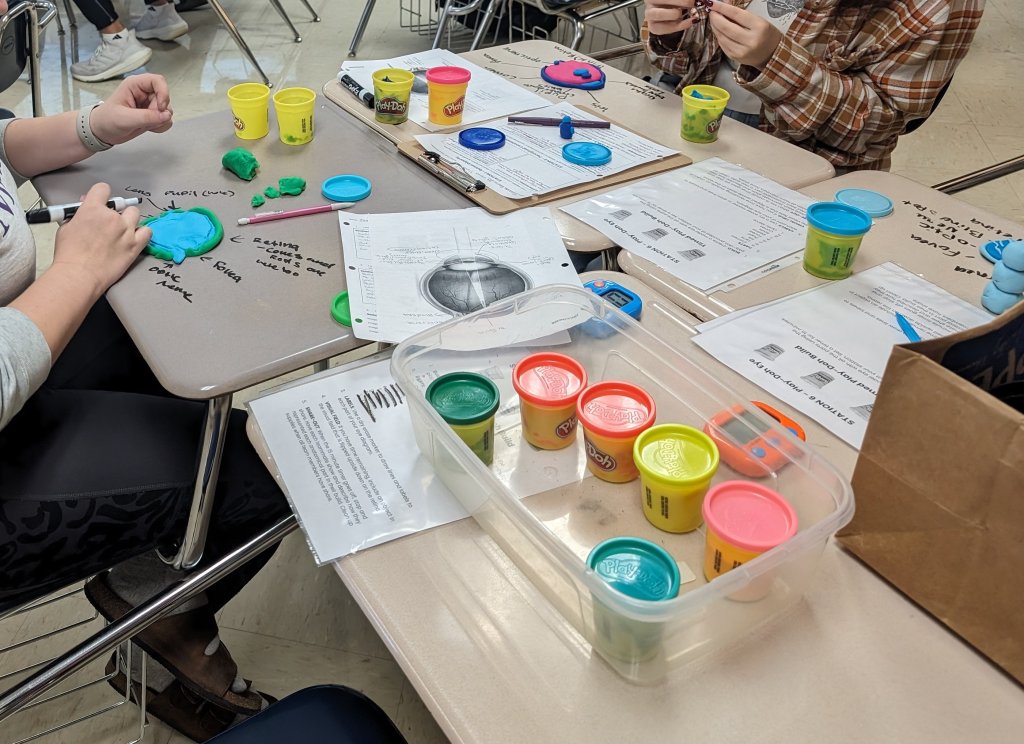

Incorporate Play-Doh builds: In many classes, students identify parts of an object, such as calculating angles or identifying landforms. Instead of labeling printed worksheets, constructing objects with Play-Doh and identifying parts with dry-erase markers or sticky notes can make this skill more engaging and interactive. For example, in my psychology class, students identify parts of the eye, ear, and brain.

Strategies like these have helped me move away from some of the traditional methods I started with and create a more active learning experience for my students. This has benefited them, and it’s been exciting for me as an educator to watch students engage with the material and one another in deeply meaningful ways.