Exploring the Power of Words

Teachers can use creative ways to spark students’ interest in words and encourage long-term retention of their meanings.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Vocabulary is an indispensable part of instruction, from English language arts to virtually any content area. As Norman Unrau, ReLeah Cossett-Lent, and other scholars of disciplinary literacy have noted, all subjects have their specific vocabulary.

Teachers of readers in middle school and high school can explore opportunities and ideas for making vocabulary about more than just writing words and definitions to be stored in short-term memory and then dropped. As educators know, the process of learning new words is never done.

The Power of Dialogue and Paraphrasing

We know from the research of scholars like Andrew Biemiller and William Nagy and Dianna Townsend that students need frequent exposure to words to move them into long-term memory. Though Biemiller’s work focuses on primary grades in many cases, dropping a list of words on students on Monday and quizzing them on Friday simply isn’t ideal at any grade level.

This process of learning new vocabulary involves more than asking students to write down words over and over; instead, I advocate for exploring possibilities of cocreating dialogue in classrooms. I tend to approach vocabulary work as a class-wide and small group activity in which we have the opportunity to practice the way words sound in our mouths. I say them, have students say them, and have students discuss them in groups with relatable statements.

Ideally, the words I choose are not only high-currency words that can be used daily (see Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Hattie's book, Visible Learning for Literacy, Grades K–12) but also words that students can readily use in writing and see again in readings that we engage in as a class.

Discussions can link new words to known words, especially for vocabulary stems, and working through definitions can be discussion-oriented to arrive at paraphrased definitions, rather than rote word-for-word copies from books. Moving definitions from what was on the page to a class-crafted definition also helps to avoid the pitfall of simply matching up words and definitions in short-term memory.

Find Creative Engagements with Words

I can vividly recall the soreness in my arm as I wrote definitions in middle school for science class. While the memory of the throbbing muscle is there, I don’t recall the words themselves or what we ever did with them as a class. That’s why I advocate for creative and thoughtful implementation and application of new words.

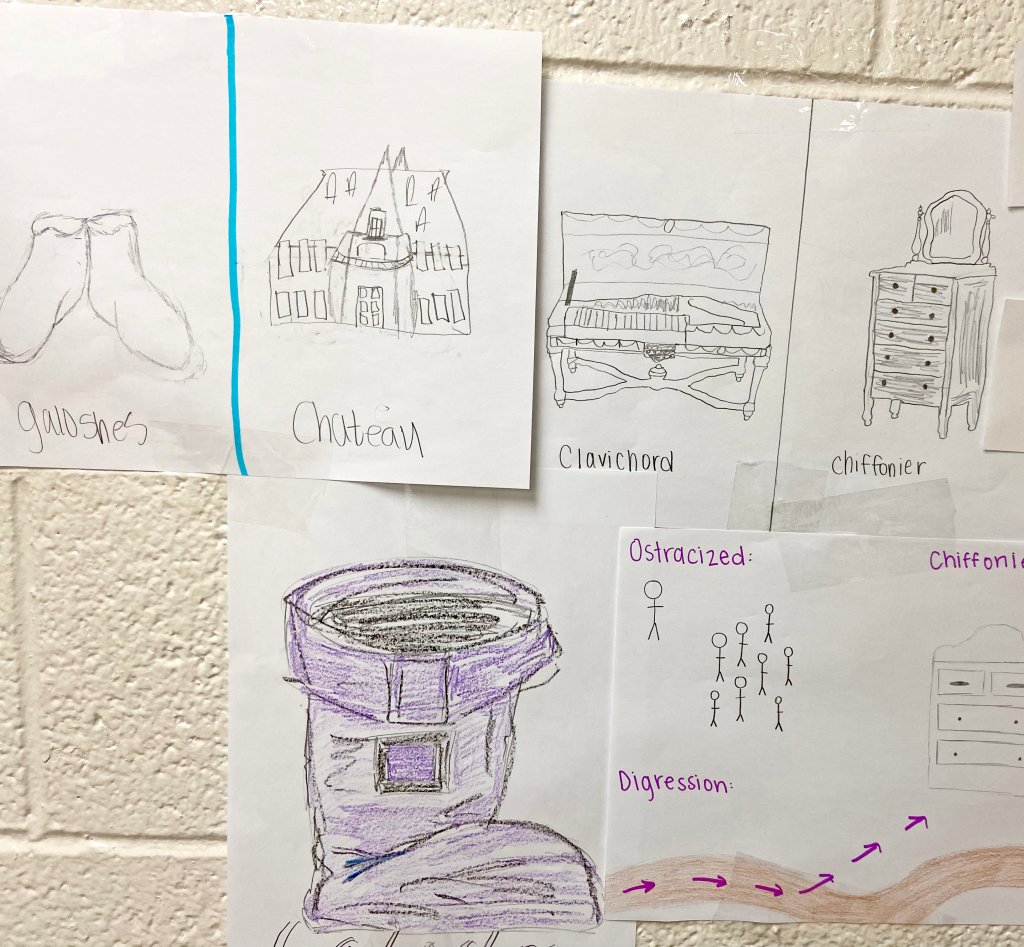

For vocabulary, creativity can mean many things, including annotations, illustrations (as in Verbal Visual Word Association), use of gestures in learning as in Total Physical Response (ever had that moment when you do something with your hands to remember a word you’re trying to think of?), and dramatic approaches to acting out words. In short, teachers have a variety of options beyond asking students to stop at writing words and definitions—including asking students to use words in their writing once word meanings have been explored.

While writing sentences with words is a common activity, I try to wait on writing until we have seen the words in context at least a few times. Otherwise, I’ve had students who might try to take a word like imprecation and fashion a sentence that works like this: “I imprecation my dog for leaving a mess” or “Imprecation is a long word.”

Once we’ve established the use and sounds of new words and seen how authors use them, I often ask students to use their words in response to a prompt, including descriptive flash fiction, information texts, or poems to relate to images that I bring in from popular culture (I recently had students respond to an image from the Disney+ Marvel movie Werewolf by Night).

Get Students Involved in Vocabulary Work

Finally, students can be an active part of working through texts in whole group or small group instruction. For students who are plurilingual, as well as students whose primary language is English, teachers can invite simple assessments about known words by keeping track of new vocabulary terms in student-created notebooks. Students can also be active in choosing words from readings that they want to know more about.

One caveat I’ve found is that students might select a character name to know more about—an interesting opportunity for exploring name choices in texts, but it’s also an opportunity to let students know they do not have to worry about names as part of vocabulary lists.

I embrace the power of a well-chosen word wall, and having students create this classroom feature with you—typing and writing words that they want to use in writing and taking part in the process—can make the word wall more than a classroom decoration. I also attempt, in the midst of all my challenges as a classroom teacher, to reference that word wall multiple times.

Other ways that I‘ve encouraged student involvement are writing analogies as a class, using vocabulary in cross-content responses (e.g., math vocabulary in break-up poems), and labeling drawings with literary vocabulary. By taking a relevant, and even humorous, approach in linking relationships and content-area words, students have the opportunity to explore dimensions of word meanings—and have a bit of fun and creativity in the process.

Celebrate the Power of Words

As I’ve just hinted, the demands of teaching are profligate (a word I would certainly add to the word wall). I reflect often on my early days of teaching and the ways that I lost track of our classroom vocabulary throughout the week in the midst of readings, writing activities, and school happenings. My overall goal with focusing on vocabulary is to create a classroom where the power of words is seen and celebrated.

Some weeks, I still find words I want to delve into, and the end-of-week quiz isn’t always the way I want to explore words. I realize that the creative composition is enough; or sometimes, using the root from the word in a new context shows me that students have embraced the power of how a word works.