7 Ways to Get Retrieval Practice Right

Effective retrieval practice strategies help students identify what they know about a given concept and retain that information for the long-term.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Teachers are often concerned with getting vital information into students’ heads, but it’s just as important to give students frequent opportunities to externalize and manipulate recently learned materials. Simple retrieval activities like flash cards, “brain dumps,” and low-stakes quizzes remain among the most effective tactics to move learners from a hazy recollection of something towards more clarity and “permanence,” writes Ulrich Boser, the CEO and founder of the Learning Agency Lab, in a new post “The Five Things You Need to Know About Retrieval Practice.”

Retrieval becomes even more impactful when teachers keep considerations like mental agility and the spacing of materials in mind. The practice of interleaving—mixing together two or more related concepts or skills instead of focusing on one at a time—keeps learners from relying on rote methods and forces them into a more productive “thinking on their feet” posture. Asking students to practice basic mathematical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, for example, tends to work better when you ask students to move between the operations, rather than practice each operation separately. Research also demonstrates that retrieving stored information at regular intervals—a practice called spacing—encodes the learning far more durably.

Finally, to connect recently learned material to prior knowledge and build more durable webs of student insight, teachers should consider “mapping exercises” like hexagonal thinking and concept maps. Here are some deeper dives into seven retrieval practices that work:

Low-stakes Quizzes

“One of the easiest ways to incorporate retrieval practice into learning and teaching is via low-stakes tests or quizzes,” Boser writes.

Quizzes and practice tests help students gauge how well they understand recently learned material, and identify areas of strength and areas where they need to grow. Research shows that when students become too reliant on strategies like rereading or highlighting material they tend to develop a false impression of how much they know—quizzes close that gap.

To get the most out of quizzes, the research suggests that it’s better to make them low-stakes–worth little or no grade–which can reduce test anxiety, prompt more honest reflection, and improve student focus and performance. Timing also matters: It’s helpful to give a practice test right after a lesson, and then continue visiting the concept through review and quizzes throughout the school year. To make low-stakes quizzes part of your repertoire, you can try clickers to do quick checks for understanding, use engaging apps like Kahoot! Or Quizziz, or opt for free online alternatives like Poll Everywhere.

Brain Dumps

Giving students just a couple of minutes in class to stop and write down everything they can think of about a specific topic or question is a great way to test their knowledge.

A “brain dump” exercise can take five minutes or less, and even the simplest version of it can help generate knowledge and create longer term retention. But it can also be modified to include collaboration with other students, says Boser: Ask them to compare their work to identify gaps, similarities, and differences, for example—and if large enough gaps and misconceptions are apparent, have them research the answers together.

Flashcards

Despite the ubiquity of flashcards, to make the most out of them requires explaining to students how they should be used—and might even require some modeling in the classroom.

For example, students should understand that for information to really stick, they should go through their card deck multiple times, and attempt to verbalize as much of the information on the back as possible before flipping them. Boser suggests that students keep cards in their deck until they are able to successfully retrieve the information by saying it out loud—in its entirety—at least three times.

Hexagonal Thinking

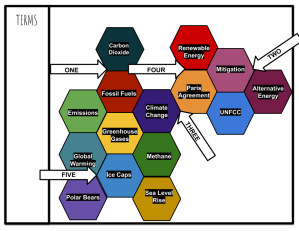

Hexagonal thinking is a mixed retrieval and elaboration strategy that uses hexagonal cards, paper, or even programs like PowerPoint or Google Slides to investigate how ideas and concepts are connected. For example, students who have just finished learning about World War II might generate a list of historical events and forces—treaties, battles, and more—and then write each of these items on hexagons before beginning to arrange them in cause and effect relationships.

When students work in a small group attempting to connect the hexagons, they inevitably come up with different combinations and different rationales. The proposed connections can be explained using arrows and an attached, written document and then shared with the whole class. An example of students exploring the forces involved in global warming is below:

Concept Maps

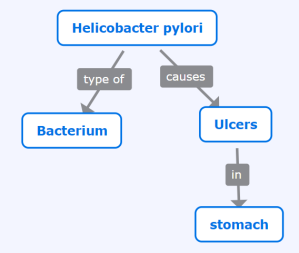

Concept maps are visual tools that help students organize and articulate what they know about a given concept or topic. Important concepts are generally enclosed in a circle or box and then connected to other concepts by a line that might include explanatory phrases to define the relationship. Examples of linking phrases are typically things like “begins with”, “includes”, or “aids.”

An example map about specific types of bacteria could look something like this:

To facilitate the activity, students can be presented with a guiding question, such as “How is ice formed?” and use the question as a springboard to help them map out their understanding of the physical process.

Research shows this strategy is far superior to rote memorization because it encourages students to make rich, meaningful connections within a topic. Writing for Edutopia, educator Dr. Kripa Sundar said the strategy can be easily adapted for early learners by replacing words in the concept maps with pictures.

Jigsaw Method

You can use the Jigsaw Method to help students retrieve information, process it again, and then practice teaching it to their peers. After splitting students up into small groups of four to six, each should be assigned to specialize in one “chunk” of content related to a topic or lesson, as seen in Cult of Pedagogy’s excellent video tutorial.

For example, a history teacher focusing on an overview about the various forms of government could divide the content into chunks such as democracy, dictatorship, monarchy, republic, etc. After each chunk is assigned to an individual student in the group, they go off to read and study their chunk independently. Later the group will reconvene, and each student will teach from their special knowledge base. Consider ending the activity by directing tough questions to each group, or letting the groups quiz each other.

Think, Pair, Share

Similar to brain dumps, “think, pair, share” is a low-stakes retrieval activity that’s relatively easy to set up. Ask students to dwell on a particular topic or question you’re already covered and get them to come up with as many facts or important ideas as they can. Once they have a list—you might want to specify how many items are ideal–the students then pair up with a partner to talk out what they know, compare notes, and help each other identify gaps in their understanding.

According to Rosie Reid, a high school English teacher in California, tweaking this activity to “write, pair, share” can help “improve the quality of the conversation” students have with each other. It can also help teachers get real time feedback on students’ understanding of the material as they walk around the room during the writing portion and do a check to see how many students are having trouble coming up with points.