6 Cool Visual Thinking Activities That Strengthen Student Writing

Visual activities like mapping, sketching, sculpting, and writing comic strips can help students clarify ideas, strengthen drafts, and deepen literary analysis.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.When readers crack open J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, they encounter detailed maps of Middle-earth—the fictional landscape of mountain ranges, rivers, forests, and marshes where the story unfolds. The maps orient readers in an unfamiliar space, but they also guided Tolkien himself. “If you’re going to have a complicated story, you must work to a map,” he said in a 1964 BBC interview, “otherwise you can never make a map of it afterwards.”

Tolkien visualized Middle-earth as he wrote, using maps to develop a consistent spatial logic in the three novels of the Hobbit trilogy. But drawing fictional landscapes before writing them is only one form of utilizing visual thinking; young writers and readers can also sketch character relationships, map plotlines, diagram themes to clarify ideas, identify moments where stronger details can enrich stories, or deepen their comprehension of challenging texts.

In English classrooms, where students are often writing descriptive essays, developing complex narratives—or wrestling with layered characters and relationships, abstract themes, or complex plotlines—sketches and other visualizations can help make thinking visible, surface new connections, reveal gaps in understanding, and strengthen drafts. As eighth-grade English teacher Stephanie Farley writes for Middleweb, visual exercises help students make connections they wouldn’t otherwise make, provide an entry point to deep, worthwhile conversations, and offer students an opportunity to exercise their creativity.

Maps As Story Blueprints

Before drafting a story, Farley asks students to sketch the setting where the central conflicts unfold and explain how that location shapes both the conflict and the protagonist—pushing them to think deliberately about why events happen where they do.

Mapping can alert writers to deficiencies in their plotlines, settings, and mental models of spaces—and thus support deep revisions and rethinking. In one exercise, a student reads a description of a setting or character aloud while a partner tries to draw it. The gaps between the writer’s intent and the illustrator’s map quickly reveal where descriptions lack clarity, showing students—not just telling them—where more detail is needed.

Mapping also deepens literary analysis. Students might draw and annotate a key setting, connecting physical spaces to character motivations and themes. In Romeo and Juliet, for instance, mapping Verona’s divided households and public spaces helps students see how geography reinforces social boundaries—and consider how relocating the story might alter the conflict. Alternatively, students might chart plot movement: mapping events in Lord of the Flies, for example, can help make visible how the boys’ increasing distance from the beach parallels their drift from social norms.

Storyboarding Literary Tasks

Before epic movies are filmed, they are meticulously planned. A key strategy filmmakers use is storyboarding, or visually breaking down each scene into a series of pictures that resemble a comic strip filled with notes on action and detail.

In the classroom, storyboarding offers students a way to visualize and stress-test the structure of their writing, deepen the revision process, and expose the absence of crucial details—like the particular dialect of a fictional community, or the dimensions of a room where a crucial scene takes place—that make drafts feel more authentic. By laying out ideas frame by frame, students can see where transitions falter, details are thin, and logic needs tightening.

Storyboards can support understanding across disciplines, too. As English and theatre teacher Darcy Bakkegard notes, the visual tool can be used to tell the “story” of a math problem, a scientific process, or a historical time period. “Really, anything can be a story,” she writes.

For example, students in a science classroom might storyboard the stages of cell mitosis—laying out the prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase in separate panels and labeling key changes as chromosomes align, separate, and divide. As their understanding of the process grows, students can go back and revise their panels to add more details about the process and further clarify cause and effect.

Drawing the Text in Real Time

To improve his middle schoolers’ reading comprehension, English teacher Chey Cheney combines visual note-taking with listening through a sketchnote activity he calls “read-aloud quick sketch.”

In the activity, students write an author’s name and the title of a text in the center of a blank page. Then, they draw a winding road from the top-left to the bottom-right corner of the page, creating a visual timeline of the text. As Cheney reads aloud, students pause at key moments to note relevant details along the road—writing important quotes in thought bubbles, circling keywords in stars, and sketching simple images to represent major events or emerging themes in the passage.

The symbols, images, colors, and layout serve as cognitive anchors that help make learning visible and memorable, explains Cheney. “The act of sketching while listening activates different areas of the brain, helping to encode the information into long-term memory,” he says. "Even weeks later, students may not recall the passage verbatim, but their sketchnote will cue vivid memories of the content."

Sketch to Overcome Writer’s Block

Oftentimes, when a student struggles to think of something to write about, Professor of English Education Todd Finley pulls out a bucket of old crayons and asks them to draw a picture of the topic. To help them overcome the fear of drawing something badly—or worrying too much about the artistic merit—Finley talks through an example of the drawing process and models a sketch with them. Once they see his “poor drawing skills,” Finley’s students embrace their own drawing.

If students write a piece that compares and contrasts relationships, Finley encourages them to use spatial representations, such as Venn diagrams or continuums. For example, if students are comparing Romeo and Juliet’s relationship to Juliet and Paris’s (to whom Juliet is originally betrothed), they might note the similarities, differences, and values of the characters in the visual. Following the pre-writing exercise, Finley asks students questions about their sketches, such as “Why did you decide to draw it this way?” or “Why did you include this detail/item?”

“Discussing the students' drawing in this way gives me, as an instructor, a very clear idea of what the student understands and thinks about the given topic,” says Finley. “For the student, it is an opportunity to articulate his or her thoughts about the topic.”

Sculpt Literary Themes Into Masterpieces

After guiding students through the close reading and annotating of a text—highlighting key language, structure, and literary devices—high school English teacher Karla Hilliard asks them to represent a major theme through sculpture. Using Play-Doh, Legos, or both, students build a physical model of their interpretation, collaborating with peers, and referring back to the text to ground their ideas in evidence. As they work, Hilliard circulates and asks students to explain what they’re making and why.

“I see students begin with ‘What am I gonna make?’” she says. “As they start working with their Play-Doh or their Legos, and they’re considering the representation of their ideas, you can see their thinking grow and evolve.”

When the sculptures are complete, students title and explain their work on a notecard, then participate in a gallery walk to compare interpretations with their peers. Hilliard notes that students’ understanding of texts “never ends where they begin” during the activity, and that familiar materials like Legos and Play-Doh help them “let their guard down, flex their creative muscles, and express their ideas in a hands-on, playful new way."

Poetry Comic Strips

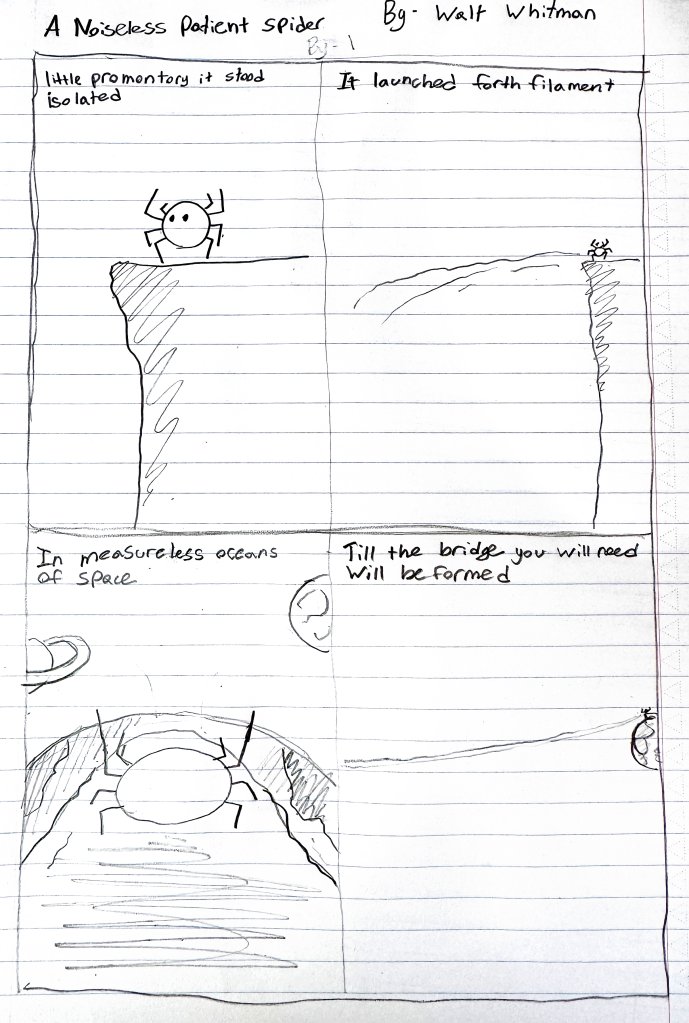

Poetry is full of playful, lyrical language that can be challenging for some students to understand—and visualize. To help, ninth-grade English teacher Brett Vogelsinger asks his students to create quick, four-frame comic strips based on a poem—in the process drawing their attention to “what they can or cannot yet visualize in the poem and how the images they can represent for patterns.”

When reading Walt Whitman’s “A Noiseless Patient Spider,” for example, Vogelsinger begins by clarifying tricky words like “filament” and “gossamer,” then challenges students to identify and sketch the poem’s four most important images in their notebooks. These four-frame comics push students to slow down, pay close attention to language, and “identify early interpretations or misinterpretations of the poem,” Vogelsinger says.

Afterward, students circulate to view each other’s work and discuss why they chose particular images and why each frame is critical to understanding the poem. This routine not only helps students “understand that poetry conjures images in our minds,” says Vogelsinger, it also helps them “make meaning out of what they read and see the value in what a poet has produced.”