3 Literacy Practices That Work

A literacy researcher shares three practices that are proven to be effective for early elementary learners.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In the post “What Doesn’t Work: Literacy Practices We Should Abandon,” I wrote, “The number one concern that I hear from educators is lack of time, particularly lack of instructional time with students. It’s not surprising that we feel a press for time. Our expectations for students have increased dramatically, but our actual class time with students has not. Although we can’t entirely solve the time problem, we can mitigate it by carefully analyzing our use of class time, looking for [and doing away with] what Beth Brinkerhoff and Alysia Roehrig (2014) call ‘time wasters.’”

In this post, I take the inverse approach: identifying three research-supported practices that are especially worthy of class time.

1. Morphology Instruction

Morphemes are the smallest meaning-carrying units in language. In reworked, for example, there are three morphemes: re- meaning “again,” work meaning “purposeful effort,” and -ed signaling the past. Research indicates that morphology instruction fosters decoding, spelling, and vocabulary development (Goodwin & Ahn, 2013).

Teaching the meaning of affixes (prefixes and suffixes) and root words is a fairly widespread (and research-supported) practice, but morphology instruction goes well beyond this. Students need to be taught to decompose and compose words by morphemes, playing detective as they figure out how to figure out a word’s meaning or build a word with a particular meaning. Starting with compound words such as cupcake, skateboard, or railroad may be helpful. Over time, students can move to more sophisticated word composition and decomposition. Based on research by Bauman and colleagues, Goodwin, Lipsky, and Ahn (2012, p.465) suggest a strategy called PQRST:

P (Prefix): find the prefix and identify its meaning

QR (Queen Root): find the root (which is queen of the word) and identify its meaning

S (Suffix): find the suffix and identify its meaning

T (Total): put the meanings of the units together to gain the word’s meaning

For English learners, Goodwin and colleagues suggest helping students use cognates as part of morphology instruction. For example, during science instruction when introducing the term lunar, help children recognize the relationship to the common Spanish word luna, meaning “moon.”

2. Fostering Motivation to Read

Designing instruction to include specific motivational practices can foster motivation to read. For example, the Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) approach, which has had positive impacts on literacy in a number of research studies (Guthrie, McRae, & Klauda, 2007), is designed to include five motivational practices:

• Relevance: Students have the opportunity to connect a current activity to previous in-classroom experiences, such as science investigations, and to their lives outside the classroom, such as a need they perceive in the community.

• Choice: Students have options within the curriculum, such as which animal habitat they want to study, which relevant texts they want to read, and how they want to present their learning.

• Collaboration: Students have opportunities to work together, whether through relatively simple activities, such as partner reading or peer editing, or more complex endeavors, such as holding a study group on a topic of interest or jointly developing a presentation or paper.

• Self-efficacy support: Students are encouraged to set goals for their work, such as reading a particular book; are helped to make those goals realistic; and are guided to attribute their successes or failures to effort, not innate ability.

• Thematic units: Students develop expertise through a structured set of experiences that cohere around a big idea and around subconcepts and cases within that idea.

It is important to note that these motivational supports should not occur in isolation. In CORI, they are linked to comprehension strategy instruction and other cognitively oriented practices, as well as to important science or social studies content.

3. Interactive Writing

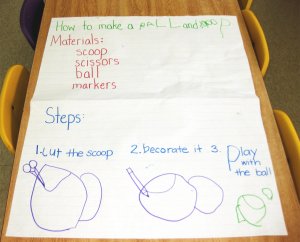

Interactive writing involves the teacher and young children (pre-K through grade 1 in research) writing together, with the teacher in the lead and the children contributing as appropriate given their developmental levels. Children and the teacher agree on a text to write, preferably one with an authentic purpose, such as to thank a custodian for her service, fill parents in on a recent field trip, or teach another class something they learned. The teacher and children compose the text together and take turns putting the words to paper. The teacher bears in mind children’s individual strengths and needs when involving them. For example, a child in earlier stages of literacy development might be invited to contribute a “o” to the text, whereas a child who is more advanced might be asked to write whole words.

During writing, the teacher can engage in explicit teaching and modeling of many literacy skills, such as where on the page to start writing (a concept of print), listening to the sounds within words (phonemic awareness), and matching the sounds to letters (spelling). Research in pre-K through grade 1 shows benefits to phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, early reading, and many aspects of writing development (Craig, 2003; Hall, Toland, Grisham-Brown, & Graham, 2014; Roth & Guinee, 2011). For more about interactive writing, see this presentation and this demonstration.

Measure of Success

Even if you don’t engage in these specific activities, they provide a sense that there are specific instructional practices with strong research support. We should privilege such strategies over others with little or no support to maximize the effectiveness of instructional time.

Notes

- Brinkerhoff, E.H., & Roehrig, A.D. (2014). No more sharpening pencils during work time and other time wasters. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Craig, S.A. (2003). The effects of an adapted interactive writing intervention on kindergarten children’s phonological awareness, spelling, and early reading development. Reading Research Quarterly, 38, 438-440.

- Goodwin, A., Lipsky, M., & Ahn, S. (2012). Word detectives: Using units of meaning to support literacy. The Reading Teacher, 65, 461-470.

- Goodwin, A.P., & Ahn, S. (2013). A meta-analysis of morphological interventions in English: Effects on literacy outcomes for school-age children. Scientific Studies of Reading, 17, 257-285.

- Guthrie, J.T., McRae, A., & Klauda, S.L. (2007). Contributions of Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction to knowledge about interventions for motivations in reading. Educational Psychologist, 42, 237-250.

- Hall, A.H., Toland, M.D., Grisham-Brown, J., & Graham, S. (2014). Exploring interactive writing as an effective practice for increasing Head Start students’ alphabet knowledge skills. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42, 423-430.

- Roth, K., & Guinee, K. (2011). Ten minutes a day: The impact of interactive writing instruction on first graders’ independent writing. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11, 331-361.