Way Beyond Fuddy-Duddy: New Libraries Bring Out the Best in Students

Good things happen when the library is the place kids want to be.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

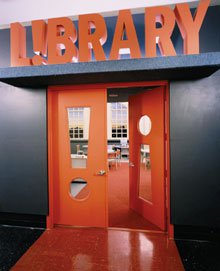

Climbing four flights of stairs to the library at PS 106, an elementary school in a tough neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, is well worth the effort. Unlike the rest of the 110-year-old school's structure -- a grand building well past its prime, with echoing halls of black floors and drab walls -- a renovated attic space announces itself with two bright yellow doors. Each is inset with large windows shaped like exclamation points -- one upside down, one right side up. It's as if the entrance dares onlookers to glimpse inside.

"Our philosophy was, libraries aren't places to be quiet. That's the reason for the exclamation marks," says Henry Myerberg, an architect with the New York firm of Rockwell Group who worked on the space. "The invitation is not just the grandeur of the doors. The windows are kid scaled, to invite them to peek at what is happening inside. So, we don't mind noseprints on the glass."

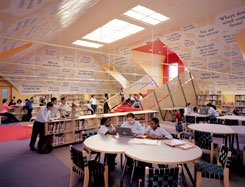

Kids who take up the invitation see something special. The spacious 2,575-square-foot library boasts loft ceilings and chairs whimsically shaped like commas, apostrophes, and periods. A bright red carpet echoing the doors' exclamation-point theme covers stairs leading to two large windows that offer a panoramic view of Manhattan. Though the city of dreams looms only a short subway ride away, many of the school's 650 students -- 95 percent of whom qualify for free lunches -- have never set foot there.

"Our goal was to make the libraries look like the most fantastical things that ever landed," says Myerberg. "We wanted to transform libraries into something kid friendly, very active, very inviting, that didn't look like a fuddy-duddy library you would normally see in a school."

For several years, Myerberg and other leading New York architects have delivered on that vision by lending their talents pro bono to a library project initiated by the Robin Hood Foundation, a nonprofit agency combating poverty in the city.

In 2002, Robin Hood, partnering with New York City's Department of Education and a merry band of top-notch architects, began transforming libraries in elementary schools in the poorest neighborhoods throughout the city's five boroughs. So far, thirty-one libraries have been completed -- on time and under budget. This fall, work begins on an additional twenty-five facilities, slated for completion within a year.

A Leg up on Knowledge

Why libraries? Speaking from Robin Hood's airy headquarters near Manhattan's Union Square, David Saltzman, the group's executive director since 1988, explains how the library initiative helps achieve his agency's overarching goal of "kicking poverty's butt."

"We want to make sure that every kid gets the education needed to claw their way out of poverty," says Saltzman with a passion undiminished after more than seventeen years of serving New York's poor. "Our goal for these libraries is that they help ensure that every student has the tools needed to build a better life for themselves and their families."

Robin Hood certainly did its homework before embarking on such an ambitious endeavor. In keeping with the nonprofit's approach of "finding, funding, and creating the most effective ways" to help the poor, the initiative seems a perfect fit. By investing in only 5 percent of a school's real estate -- what Robin Hood estimates a library constitutes -- it has an impact on 100 percent of the students, as well as their parents and the local neighborhood.

Each library costs roughly $750,000 to refurbish. For every dollar Robin Hood ponies up for the project, the Department of Education matches it with two -- not counting the foundation's free books and architectural services.

The library initiative helps fill a gap in the New York City public school system, which includes a population of 1.1 million students, 40 percent of whom read below grade level. When Robin Hood began research for the library project in 1979, it found that fewer than one-hundred of New York's 650-plus elementary schools had anything resembling a library -- and that the entire New York system had fewer than ten certified public elementary school librarians.

A Recipe for Designing Delight

The attic at PS 106 -- a place where, as the school's principal Robert Flores says, "students look for any excuse to go" -- contains design elements all Robin Hood libraries share. Myerberg refers to these design criteria as a "recipe," and one key ingredient is flexibility.

Each library has an open space -- typically about 1,700 to 2,500 square feet -- that can be reconfigured for multiple functions. At PS 106, for instance, the chairs and tables are moved around to create a mini-theater where kids perform skits and plays. The space can also be rearranged so two classes function simultaneously, or reconfigured for hosting events for the broader community, from PTA meetings to poetry readings.

Another guiding design principle is the idea that libraries are not merely static repositories for storing books but should also be exhibition spaces for works created or inspired by kids. With this concept in mind, at PS 184, in Brooklyn's Brownsville neighborhood, enlarged colorful photomurals of students fill the gap between the bookshelves and the high ceiling. "That was a way of making the graphics school specific," says Richard H. Lewis, an architect who worked on the library.

From Why to Wi-Fi

At PS 42, in Far Rockaway, Queens, serpentine bookshelves wind around the library. "We wanted to make reading fun, so we made the wall a kind of bookworm with cut window seats at different heights," explains Marion Weiss, of Weiss Manfredi Architects. To enhance that sense of fun, Weiss says, they also designed bean bag chairs on wheels.

The PS 106 library makes its distinctive mark in a different way: The top half of the bright yellow walls sport dozens of large white dialogue bubbles painted with questions students have posed: "Does the ocean have a drain?" "Do soles have souls?" "Do cows ever dream of girls?" "Will I ever be what I want to be?"

Below, students can find the answers to many of the more practical questions in the ten thousand books lining the room. Well-stocked bookshelves surrounding open space is another common feature in these libraries -- two publishing houses, Scholastic and HarperCollins, have each donated a million books to Robin Hood -- or inquiring young minds may seek answers online. Each library is also outfitted with four desktop computers and four laptops, complete with Wi-Fi capabilities and high-speed Internet access.

"I can't underscore [too much] how important this technology piece is," says Robin Hood's Saltzman. "If the libraries just had books and great librarians, they wouldn't be half as good as they are with technology. Technology helps capture the imagination of students, and it provides them with access to the wisdom of the world."

Also underlying the libraries' design is an architectural truism: First impressions matter. That's certainly what Myerberg adhered to when working on the library at Charter School 50, in the South Bronx, the first completed as part of the Robin Hood initiative. (So far, Myerberg has worked on seven libraries; this year, he'll bring his visual and philosophical style to five more.)

Like PS 106, CS 50 requires a trek up several flights of stairs. And, like its sister library, it contains brightly painted doors with exclamation-point-shaped windows, the library initiative's trademark logo.

"You make the long climb up those stairs, and the library is a reward. It pronounces itself: 'You have arrived at the library,'" says Myerberg. "All the other doors in the school, they're just normal doors. But this door says how important the library is."

Such design elements exemplify how the Robin Hood Library Initiative defines the school library's role in the twenty-first century: a place for collaboration, performance, creativity, interactivity, and exploration, both online and offline. It's a hub, not an add-on luxury.

"There's nothing forbidden about these libraries," says Robin Hood's Saltzman. "There's nothing scary. There's no schoolmarm with her hair in a tight bun, punishing you for talking above a whisper. At times, these libraries are raucous."

The signature exclamation points also encourage a liberation from a stereotype. "An upside-down i represents the turning on its head of all those negative notions of what a library was. That exclamation point is what it's all about -- the emphatic invitation to learning."

In a kid's mind, the reimagined libraries are definitely a place to discover more about the world around them.

"When I come in here, I like learning about books I didn't know about," says eight-year-old Maureen, a third grader at PS 106. "The books remind me that there's a lot I don't know." She particularly enjoys sitting on the library's soft-carpeted red steps, which double as seats. "I love sitting there to think about things. I want to learn about Egypt. I want to know how the pyramids got built."

Benefits Beyond Books

Though the libraries' architects adhere to their design principles, for its part, Robin Hood has a few criteria of its own. First, the organization requires that all facilities be staffed with a full-time certified librarian holding a master's degree in library science, along with a full-time aide. The project even provides funds for someone to earn his or her degree, if necessary.

That was the case with Miriam Piñero. After fifteen years as an educator working as both a bilingual teacher and a resource teacher, Piñero earned her library science degree. Today, she runs the library at PS 106. "The kids love it here," says Piñero, explaining that many of the school's students come from low-income homes. "They can't go out and buy these books."

Piñero seems a perfect fit for the school's largely Hispanic student population. In addition to meeting with teachers to determine which books might enhance their curriculum, she also orders bilingual books. (One class per grade operates in two languages.) She figures that more than 50 percent of the students check out books regularly.

When it comes to selecting schools for the library initiative, Robin Hood looks for strong leadership. In the case of PS 106, school principal Robert Flores was an easy choice. When Robin Hood's representatives met with him, he said, "You aren't getting out of here without my students getting a library."

Robin Hood also selects schools that show progress on test scores. "We're looking for schools that are not at the top and schools that are not at the bottom," explains Saltzman. "We want to see test scores that are improving."

For PS 106's principal, the attic space isn't the only magical transformation at his school. Since opening the library's big yellow doors last year, he's also seen a change in the student body. How?

"Attitude," exclaims Flores without skipping a beat. "Now, they've got a good attitude. Our kids think they're special. And they think they have the best library in the world."

Now, when those kids climb the steps of their awesome library to look out on the Manhattan skyline, they may actually see a world of possibilities.