A Remarkable Transformation: Union City Public Schools

The teachers and community — and a large dose of technology — come together to save this New Jersey school district.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

In 1989, leaders of Union City Public Schools in New Jersey had a choice. They could continue the same unsuccessful programs that had led to the threat of a state takeover for failing forty-four of fifty-two indicators of educational competence. Or, they could retain local control by demonstrating academic progress.

Unlike school districts in nearby Paterson, Jersey City, and Newark, which were taken over by the state and have yet to return to local control, Union City improved, and in fact flourished. Fourteen years after that very real takeover threat, schools in Union City are models for reform, and visitors from Chicago to Argentina are replicating its practices.

Measures of Success

Test scores have shot up to the point where they're the highest among New Jersey cities. Eighty percent of the district's students currently meet state standards, up from 30 percent. Attendance at the eleven-school, 11,600-student district increased, dropout and absence rates decreased, and students have been clamoring to transfer into Union City schools.

Children are allowed to learn at their own pace at Union City schools.

Credit: EdutopiaIn one seven-year period, passing eighth-grade test scores jumped from 33 to 83 percent in reading, from 42 to 65 percent in writing, and from 50 to 84 percent in mathematics. College-going rates have increased, and the number of Union City graduates accepted at top institutions like Yale and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology jumped from eight in 1997 to 73 in 2001.

Literacy was the top priority in Union City's reform plan.

Credit: EdutopiaWhat It Took

A combination of focused leadership, a comprehensive, research-based overhaul of the system, technology, teacher and community input, site-based decision-making, and more (and carefully targeted) money explain the turnaround.

"We really began with trying to determine a philosophy of education for the school system," says Fred Carrigg, executive director for academic programs for the district, and, along with Superintendent Tom Highton, the force for pushing for profound, teacher-sanctioned changes. "When we looked at what existed, it essentially was four or five sentences that were nothing more than platitudes ... but it had no meat or direction to it."

The district gave Carrigg and a group of teachers and administrators a summer to do research -- "to find out what the trends were in American education, what people were saying, and to establish a philosophy of education."

To support the vision that emerged -- one that put literacy first and embraced rigorous interdisciplinary projects, individual instruction plans, and parental involvement -- the district switched to block scheduling, cooperative learning, and eight-week assessments to keep regular track of student progress and to note areas of weaknesses and strengths. Algebra was introduced in eighth grade. Every course had an interdisciplinary theme, which all students worked on, although they might work at different levels. District-paid professional development hinged on substantive instruction, and Union City now boasts one of the largest teacher populations with ESL (English as a Second Language) credentials and Master of Arts degrees. Many teachers were initially reluctant to adopt the changes, but Carrigg says most came around. "When the scores began to go up and things began to change, they came on board."

Fred Carrigg, executive director for academic programs, checks out computer presentations by students.

Credit: EdutopiaHigh Expectations

Another essential ingredient -- possibly the most important, according to Carrigg -- was higher expectations for a population of mostly poor students from Latino immigrant families, 75 percent of whom did not speak English at home. "Probably the biggest weakness of urban schools is the belief that these kids can't make it and can't succeed," says Carrigg.

"Most of America views certain school districts with little faith and little acknowledgement," agrees Union City graduate Oscar Negroni, who went on to New York University. "But I think that stems from the faculty and administration who have little faith in their students. In Union City, there's a lot of faith. They push us."

The district uses reading software programs that allow for individualized instruction.

Credit: EdutopiaStudents As Workers

Throughout the classrooms in Union City's eleven schools, the trend is to eliminate rows of desks facing a blackboard and passive students listening (or not) to forty-minute lectures. Students more likely will be working individually or in groups -- often at computers -- while the teacher circumnavigates the room, stopping to advise or confer when needed.

Kindergartners through third graders may be at varying stages of Wiggle Works®, a software reading program that allows children to read (or have read to them) interesting literature. They can stop the presentation and have words or phrases repeated as many times as needed. They can record and play back their own voices, and they can write and illustrate their own versions of the book and have that book read back to them by the computer. Middle schoolers may be demonstrating their flash and animation projects on the Civil War, incorporating history, literature, and art from the period. High school students may be creating a news show video about the Great Depression or explaining why Willy Loman is a tragic hero while making a PowerPoint® presentation.

While a solid, research-based curriculum put Union City on the road to achievement, technology is what pushed it to great heights, Carrigg and other teachers believe.

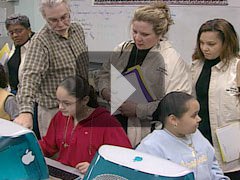

Visitors from Chicago take away ideas from Hudson Elementary and Principal Silvia Abbato to use at their own schools.

Credit: EdutopiaThe Power of Technology

"The Internet just broke down the walls of my classroom," says twenty-seven-year teaching veteran Marjorie Zaccagna, who was born and raised in Union City. "We could look up anything. There was no longer, 'That's a good question. I'll come back with the answer tomorrow.' Well, why tomorrow? We'll get the answer right now." With technology, which Zaccagna describes as "a shot in the arm" to her teaching career, she has "so many different ways now of getting [students to learn] without having to stand up there and lecture at them."

Senior Andrea Tapia says she has benefited immensely from technology. "At other school districts, they're blind to technology -- just basic environments where you go into the classroom, you learn off the blackboard, you go home, you do your homework in your textbook, and you come back to class and you present it, which is boring. And that's why students lose interest in wanting to learn."

The district made the decision in 1992 to put a couple of computers in every classroom at about the same time that Bell Atlantic decided, in a program called Project Explore, to wire and donate computers to all the teachers and students at Union City's Christopher Columbus Middle School. The results were so positive that district officials decided to use much of the new money coming to the district (the result of a school equal-financing court ruling) on computers, connections, and software. Union City now has one computer for every three students and all of its classrooms wired for the Internet.

Student work is contained in electronic portfolios that are regularly assessed.

Credit: EdutopiaMoney and Teachers

"None of this happens without money, but a lot of that can be and should be a restructuring of how money is expended," says Carrigg. He notes that while a number of New Jersey school districts in poor communities saw their funding increase more than threefold over twelve years, only Union City used the money in such a way as to produce an impressive turnaround in student performance -- with technology the drawing card for students.

But Carrigg gives the majority of credit for the transformation of Union City to the teachers who finally got a say in how to educate children. Too often, he says, teachers are "handcuffed and not given the opportunity to be the professionals they are. ... This is what these good teachers knew needed to be done."