Principals Are Key Players in School Reform

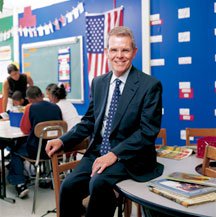

Thomas Payzant, the outgoing head of the Boston Public Schools, talks about how to best attract — and keep — school leaders.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Thomas Payzant believes this: "We will never improve American education for students one school at a time." So, when he took the helm of the Boston Public Schools -- a district with 58,000 students and 4,700 teachers, and in which 73 percent of children live in poverty -- he thought big. In his eleven years as superintendent, he shepherded a set of ongoing reforms called Focus on Children. One of the most critical goals, he says, was cultivating strong school leadership.

Within his first year, Payzant created a leadership team, inviting one principal from each of the city's nine school clusters to serve. The biweekly team meetings enable Payzant to work closely with the cluster leaders to better understand what his office must do to support school improvement. These leaders also act as coaches to other school chiefs in their clusters, so that principals, like teachers, can continue growing professionally.

He also established the Boston School Leadership Institute, which recruits and trains people with leadership potential and provides support during their first two years as principals; graduates of the institute's yearlong fellowship receive a Massachusetts Initial Principal License and commit at least three years to the Boston Public Schools.

Alongside these reforms, Payzant revamped curricula and convinced the School Committee to order all comprehensive high schools broken into smaller, more personalized learning communities.

When he retires on June 30, Payzant will leave a prominent legacy. Under his leadership, student scores on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System climbed by tens of percentage points across categories. Boston has earned a finalist slot for the Broad Prize for Urban Education in every one of the five years since the prize was created.

Payzant himself won the Council of the Great City Schools's Richard R. Green Award for excellence in urban education in 2004, and the Broad Foundation (see the Edutopia article "Class Act: Former Business Executives Put Their Skills to the Test") calls him one of its "heroes." Though he is leaving public education, he'll still be a major player in school reform: Beginning in July, he'll become a senior lecturer at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Here, Payzant describes his vision of how to make principals key players in successful reform.

Why is the principal's role so crucial?

We used to think of principals as managers and operations people, but now, at the school level, improving student achievement and closing the achievement gap are the keys to success, and principals have to lead that work at the school. Principal leadership is the second most critical variable the school has for impacting student achievement, the first being the quality of instruction in the classroom. The principal has to be the teacher of teachers.

What makes an effective principal?

Being able to relate to all kinds of people, appreciate individuals for who they are, embrace diversity. The principal leads the joint effort to make sure every child can reach high standards of achievement.

How do you recruit them?

We grow our own. The competition in metropolitan areas is strong for principals, and there is often a challenge just to keep pace in terms of compensation. After our full-year fellowship program, our principal fellows, in many instances, are ready to step into the principal role or an assistant principal post. That is our major pipeline for helping develop the leaders of the future for Boston Public Schools.

How much autonomy should a principal have?

They should have autonomy to hire teachers. Then they should be accountable for providing support for those teachers and determining whether they are meeting the standards in the school. There needs to be a relationship between the autonomy a school has and the results the school is getting, measured by student achievement. So the better a school is doing, the more autonomy it can handle and should be given.

How can they motivate faculty to enact reform, especially given the day-to-day challenges teachers face?

Effective principals develop strong relationships within the school, with the adults on staff, with the parents, and with the students. The conversation focuses on what is best for children, not what is best for the adults.

How can district administrators best serve their principals?

Ideally, a school district's central office should exist only to support and serve the educators and the students in the schools. There has to be a very intentional focus coming from the superintendent setting the expectations for district support. That includes asking the people in the schools how well the central office is doing, what's working for them, what's not working for them. Data are powerful, and leaders have to be willing to ask questions and encourage people to answer them sincerely, even if it may result in the leader getting some information she or he doesn't really want to hear but needs to.

What do principals need from the school district to succeed?

A school district budget typically has 80 percent of its dollars in people. Principals need help in recruiting the best candidates for positions in their schools, inducting those teachers in a way that they're going to be well received and helped in their first year, and getting resources for ongoing professional development to make beginning teachers into career teachers and teacher leaders.

Why is it hard to retain good principals? How do you keep them?

There has to be a support system for principals in terms of their professional development. Every first-year principal has a mentor, an experienced principal to work with. A group of first-year principals meets monthly with a couple facilitators to talk about the challenges they're facing and provide support for them in addressing those. The first group several years ago was so supportive that they wanted a group for second-year principals, so we now have that as well. And then there is districtwide professional development that we do with a three-day summer institute for all principals every summer, and periodic professional development with principals during the school year.

It seems counterintuitive that principals would need training; they've already been through the ranks.

They used to be groomed to be managers, which often left very little time to focus on curriculum and instruction. There's been a sea of change that now requires principals to know a lot about teaching and learning, to spend time in classrooms, to participate in professional development with teachers. Ten years ago, there would not have been the requirement that every school in the city have an instructional-leadership team with teachers and the principal working together to develop the whole-school improvement plan and keep a laser-like focus on all students learning and achieving.

Is that a good thing?

I can't imagine an organization anywhere that can work unless the leader is very clear on what the mission of the organization is, what the expectations are for outcomes. You've got to know the work to lead the work.