A Chilean Challenge: Focusing on the Individual to Confront Educational Inequality

In Chile, where education resists innovation, a small, determined charter school is going mano a mano with the status quo.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

As the World Learns | Austria | Bulgaria | Canada | Chile | India | Japan | New Zealand | Pakistan | Room to Read | Russia | Sweden | Uganda | More Edutopia Resources

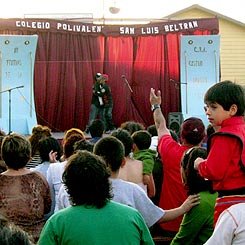

When elementary school students arrive at Colegio San Luis Beltrán, located in a poor neighborhood of Santiago, Chile, they don't sit down at their desks and wait for the teacher to tell them what to do. Instead, they retrieve their personal folders from cubbyholes along the wall and settle down to work individually on a mat on the floor. What they study is up to them -- within limits.

"They have a work plan they have to complete, a plan that lasts about a month and a half," explains the elementary school and middle school head, Carlos Olivares.

The students choose what to work on at a given time, and learn using hands-on material as well as conventional schoolbooks. They also work at their own speed, though teachers keep an eye on how well they're progressing. The teacher circulates, helping students or suggesting that a quick learner help a classmate who's having more trouble. "When you need help, they help you," says fourth grader Catalina with a wide smile. "They give us attention."

This individual work period lasts forty-five minutes and is the cornerstone of a personalized education program the school uses in grades P-4. In those grades, every school day begins with individual work. Afterward, before moving on to more traditional group classes for the rest of the school day, the students form a circle to share what they learned and how.

This approach may seem familiar to many teachers in U.S. schools, but, combined with strong parent-involvement and family-support programs -- including evening classes for parents who never finished school -- it makes Luis Beltrán unique among Chilean schools.

In this country where critics and the public often cite the low quality of education, especially for the poor, localized funding for public schools and a proliferation of expensive private schools creates a vast divide between poorer and richer students' schools.

This educational inequality was a key complaint in recent years during massive student protests that rocked Santiago with marches and school takeovers, leading the government to undertake a still-ongoing reform effort.

Reformers and protesters trace inequality and other problems in the education system to changes during General Augusto Pinochet's seventeen-year military dictatorship, which ended in 1990.

Learn to Think -- the Facts Will Follow

Olivares says Pinochet's educational legacy is directly at odds with personalized education. "With the military government, everyone was seen as a number," he says. Critics say many Chilean teachers are still too focused on transmitting a static body of knowledge, and don't emphasize the development of skills such as critical thinking.

By contrast, Cristian Infante, director of Luis Beltrán, and Olivares both say the school focuses on thinking and the individual rather than only on facts and memorization. But perhaps because of the changed emphasis, the school is also doing well on the facts-based front: Its students achieved the highest scores in their school district on the country's 2007 national assessment tests.

Olivares says the school is a popular destination for university education students doing practical training -- a fact that may help its innovations spread.

In addition to recognizing and accommodating differences among students, the system is designed to foster autonomy in the students, from the independent nature of the work itself to getting and returning all their materials.

Olivares sees another difference between his school and the remnants of Pinochet's system. Under the military, he says, "the most important thing inside a classroom was discipline." He adds that most Chilean schools continue to use a rigid disciplinary system in which "inspectors," not teachers, handle problems by consulting a rule book to find automatic punishments for a litany of misbehaviors.

Olivares says Luis Beltrán uses a guide agreed on by parents, students, and school representatives that offers a gradually escalating series of steps to respond to problems. First on the list is a one-on-one between the teacher and student, after which administrators meet with the student and ultimately the family if problems persist.

As Goes the Family . . .

The school's policy of reaching out to families distinguishes it from other Chilean schools. As one parent volunteer puts it, "I connected a lot more with this school, because in other schools the parents arrived at the door, left their children, and attended meetings only to find out what grade the child got and how much they had to pay for activities."

Since Luis Beltrán's founding fourteen years ago, the school's faculty has worked hard not only to involve students' families but also to provide support. Through a connected foundation, the school delivers food baskets to needy families and provides medicine for those who can't afford it. This community aspect is so unique that it won a 1999 Ashoka innovation fellowship for one of the founders, Carmen Cisternas.

Part of the family support are the evening classes for parents. Janet Piña, who left school more than twenty years ago, attends the night school with her son, a former Luis Beltrán student who failed his junior year.

"First, he repeated the first year of high school, and after that, the third year of high school," recalls Piña. "Because I was also missing the third and fourth years of high school, we had the great idea for us both to study together."

Now, Piña and her son are finishing their studies. "We're going to graduate!" says the forty-year-old, breaking into laughter. "I'm proud, because it's super hard, but all the same, I've done it."

Laila Weir is a contributing editor and writer for Edutopia. Her work has appeared in magazines, newspapers, and online publications around the world.