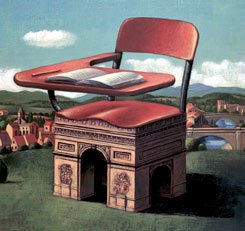

Getting Beyond the School as Temple: What Do We Expect from Our Schools?

Our concept of a community school must evolve — rapidly and intelligently.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

The concept of the community school and the related idea of the school as literally the center of its community have in a short time become sacred cows in many education circles. As soon as someone expresses either idea as a goal, or attaches it to a design proposal, any meaningful discussion of where it fits in the future of education becomes almost impossible, and the need for tomorrow's schools to deal with tomorrow's needs gets lost in the mist of nostalgia for yesterday's schools.

Community schools are by definition open to the community after school hours and on weekends. They are places where students and local people can gather for extracurricular, social, and academic pursuits. The noble goal is to provide a place where the divide that often exists between a school and the community can be eliminated. It's a perfectly laudable idea, and one that might seem worthy of sacred cow status.

The idea of a school as the center of its community goes a step further. If a community school is about catering both to the needs of students and those of the entire community, why not place the school near the center of that community? Certain town planners and architects have interpreted this inclination literally, making the community school easily accessible to all. Another interpretation is metaphorical, elevating the school to the status it deserves regardless of its physical location. Once again, these are laudable goals that might seem hard to find fault with.

Go below the theoretical surface, however, and the concept becomes a lot less ideal. The problem with community schools, whether at the center of a community or not, is that they tend to confirm an existing institutional shibboleth -- that a central repository of knowledge called school will be the place where all or most learning takes place. The community component is an add-on that rarely represents a fundamental change in the traditional education model. The word community has such emotional power, however, that it precludes a close examination of the school itself.

In their eagerness for a school to achieve the status of a community school, education stakeholders, from administrators and planners to parents, are distracted from asking crucial questions such as "As we move deeper into the twenty-first century, what will education look like?" and "How should teaching and learning and, by extension, learning environments respond to changing needs?"

Ironically, we already know the answers to these questions: In order for education to work in this century, it should be student centered, not teacher centered; it should be personalized, not mass produced; it should be connected to real-world experiences, not classroom simulations; its communications technologies should cut across local, state, and national boundaries in real time; it should be a testing ground for new ideas and technologies; and it should model and then build new social, economic, and democratic structures. Simply put, today's educational vision should be vastly different than what we had (mostly) for the past fifty years. By necessity, the places in which children and adults learn in the future should also look very different from the schools that we too often continue to build.

The community school, however, accomplishes none of the above goals. Instead, it takes an existing, outdated fortress/temple model of education and perpetuates it for the next several years. And if we are drawn in by the allure of the community-schools model, or that of schools at the center of the community -- mesmerized by the magic of that focal word -- we are all too likely to ignore a new paradigm of education that requires equally novel physical structures.

So, what are the alternatives? Let's consider two other ways to go (each of which, by the way, incorporates the C word): the community learning center and the community as school.

The Community Learning Center (CLC)

In this model, focus is shifted away from school and onto learning. By changing the focus from the school at the center of the community to learning at the center of the community, we are able to evoke a richer, more diffuse twenty-first-century vision.

The change is not just semantic. The community's role in this approach goes well beyond simply using school buildings after hours. Instead, community residents and institutions become active partners in education. Just as the school serves the community's interests, so also the community serves the school's purpose. School under this scheme becomes redefined as a learning center with pedagogy as a two-way street, as resources are passed back and forth between the center and the community.

The advantages of this design are that the traditional isolation of the fortress model breaks down. Whereas a community school might easily become just a typical cells-and-bells model into which the community is granted entry after hours, the CLC model engages various segments of the community in the day-to-day life of students of all ages and naturally enables project-based learning. One good example of a CLC is the Brookside Centre, in Melton, near Melbourne in the Australian state of Victoria. Here, a common piazza serves both the school and the community at large, and facilities such as a library, an art room, and a fully equipped technology center are shared between a government school and two private schools. The gymnasium, meanwhile, is a joint venture between local government, a nonschool sports group, and the schools, and the playing fields represent a partnership between the community, the schools, and a local soccer club.

The Community as School (CAS)

The differences between a CLC and a CAS are subtle but important. Both models rely heavily on the community to participate actively and directly in the educational process, but it is the CAS that truly moves beyond the time- and space-based framework of learning most community schools are stuck in today.

The CAS model sees the learning lab as the community itself -- including the home; the school campus becomes a gateway to the larger world of learning outside rather than a location-dependent font of all knowledge. In its ultimate incarnation, the CAS would eliminate the physical school altogether, because the school could be any place in the community on any given day. The best places to learn are often outside the classroom, and school can exist in a hundred places in a hundred forms.

Mawson Lakes School, in Mawson Lakes, near Adelaide, South Australia, itself has no defined boundaries, and K-12 students routinely use the various community facilities alongside higher-education students and community residents. Some of these facilities, such as the resource-rich Mawson Centre, were designed from the ground up to serve the learning needs of the community at large.

Closer to home, two Minnesota schools -- the Interdistrict Downtown School, in Minneapolis, and Duluth's Harbor City International Charter School -- depend extensively on students using community resources as an integral part of learning. The Metropolitan Regional Career and Technical Center (the Met), in Providence, Rhode Island (see "High School's New Face," November/December 2004), and Sevenoaks Senior College, in Western Australia, are also good examples of schools at which students obtain a significant part of their education through outside work experiences.

As the pace of change increases, lifelong learning has become a necessity. Everyone in the communities of tomorrow (not the day after tomorrow) will be a client of education, and it will be pointless simply to try retrofitting aging paradigms. The phrase "old school," once an indicator of bedrock tradition, has about as much relevance to our technological, social, and educational lives today as golf clubs that admit men only. As for the word community, in the new world of education, it must be applied in its fundamental meaning of essential connections. Schools, whether real or virtual, will in the future be about connecting individual aspirations with a joint vision, and about creating a road map to get there. The fortress won't get that job done.