How to Deal with Emotional Response to September 11

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Every September 11, I read a news story that connects me to the grief of a stranger. Today, it was one about Alissa Torres, a woman widowed on 9/11 who still clings tightly to her dream that there was, somehow, beauty in her husband's death.

I read Alissa's story this morning and cried. And now, as I do each year, I'm trying to figure out how to assimilate that personal history into my life -- how to keep it close enough that I never lose a gut sense of its importance, even as I turn my attention to the present (which includes the broader social, political, and military mess those attacks left behind).

It's hard enough, as an adult, to grapple with the quantity of pain that day produced and the depth of depravity that caused it. It's tricky, also, to trace how those terrible events influence us, personally and politically, today -- and how they will shape our society for generations to come. As a teacher with 20 or 30 kids in your care, how do you help your students make sense of all this, too? Particularly when some of them weren't even born when the attacks occurred.

In one of our earliest Edutopia magazine articles, writer Carol Pogash described how children cope when their teacher is called to serve in war. "I feel like a chunk of my life is gone," wrote fifth-grader Cody. David Spiegel, then associate chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, responded to Cody's honesty thus: "It shows me that kids are smarter than adults. They don't carry on as if life is normal when it isn't."

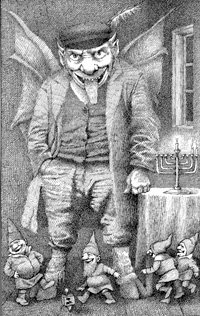

Earlier this week, at San Francisco's Contemporary Jewish Museum, I went to the opening of an exhibit on the children's stories and illustrations of Maurice Sendak, and I have to wonder whether the timing was only accidental. Sendak's work, beloved for decades by kids and parents (and a favorite in my home growing up), uses childlike imagination to confront real anxieties and fears -- feelings he experienced as a child in New York City as his Polish relatives were killed, one and then another and then another, by Hitler.

Though the monsters in his classic book Where the Wild Things Are turn out to be easily tamed, that's not true of all his beasts, some of whom are truly monstrous. In the exhibit, Sendak describes them as "demonic people, wild things, something in disorder that races through the world, and that we have to live with." Sound familiar?

The museum's curators explain that Sendak "finds important truths in the logic children use to cope with reality. . . . Because his villains and monsters represent forces of 'disorder,' stories about challenging, overcoming, and befriending them are a form of resolution for Sendak."

So maybe, through helping children understand this horror in our recent history, we can also help find healing and resolution for ourselves.

You may find some ideas and insights in two more past Edutopia articles: one on New York City teens turning their 9/11 grief into action, and one on the nature of resilience. Tell us what you think: What do you remember about that chilling day? How do you help your students understand it? And how do your students help you?

-- Grace Rubenstein, senior producer