Early-Childhood Education Takes to the Outdoors

Kids in Waldkindergarten, also known as forest kindergarten, are building fires and braving the snow. And they’re all the better for it.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

"I made a snowman today," my first grader squeals as I pick him up from school on a fresh, snowy January afternoon. It's hard to contain my surprise and delight. "Hooray!" I think. "They allowed them to play in the snow during recess." I say, "That must have been so much fun. Did you manage your snow pants all right?"

My son stares at me. Obviously, I have it all wrong. Slowly and condescendingly, he corrects me: "We made a snowman on the computer, not outside!" Silly me. They made a digital snowman.

Think Outside the Classroom

For most families in our Long Island community, keeping kids indoors for recess on a snowy day isn't a shock; it's expected. Our family relocated to the United States four years ago, after living in Zurich, Switzerland. Returning has brought many cultural adjustments, but perhaps most striking has been the pervasive, fearful attitude about children and outdoor play, particularly in less-than-ideal weather.

In Zurich, my son attended a Waldkindergarten, which literally means "forest kindergarten," although it actually serves kids ages 2-6. As the name implies, forest kindergarten takes place outside -- not most of the time, but (with the exception of inclement weather) all the time, from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., five days a week. Wet or warm, sun or snow, the students in waldkindergarten learn through exploration in an unconventional classroom: the woods.

Forest kindergartens are spreading in Europe, with a particularly large concentration in Germany, where there are approximately 700 programs. They are beginning to inspire some programs in the United States, too. These unusual schools offer educators an opportunity to think outside the box -- or, literally, outside the classroom -- and envision a dramatically different style of education that emphasizes direct experience, self-directed inquiry, teamwork, and self-reliance.

At my son's school, children arrived in the morning outfitted with backpacks and waterproof hiking boots. They were expected to dress sensibly in rain gear, snowsuits, or sun hats, as appropriate.

I grew to love a wise expression the teachers used: "There is no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing." Despite parental fear that exposure to inclement weather sickens children, our experience was that children -- including our son -- who regularly spent time in the open air (properly outfitted) stayed healthier than those kept indoors, despite winter temperatures that average around freezing.

Forest kindergartens have little or no need for commercial playthings or the typical teaching materials. Sticks, acorns, leaves, and other natural treasures become props for dramatic play, tools for science experiments, and math manipulatives.

I watched children in my son's class, for example, collect pine cones and spontaneously sort them into categories by size -- a premath exercise without the need for any fancy sorting toys or teacher instructions. Teachers keep direct teaching to a minimum, believing that children who explore nature's resources freely will develop the skills needed in the higher grades.

Research so far bears out their belief. A 2003 study at Switzerland's University of Fribourg compared the skills of children in conventional kindergartens with those in a full waldkindergarten program. The forest kindergartners performed as well as conventional peers on fine motor skills and significantly better on tests of gross motor skills and creativity. The forest kindergartners were also able to offer more solutions to problems.

Learning Comes Naturally

At the school my son attended, the day begins with an hour's hike into the Wald -- German for "forest" -- where students spend most of the day exploring around a circular structure known as the Waldsofa, or (you guessed it) forest couch. It's a roofless shelter consisting of walls made from sticks that surround benches arranged in a circle.

The group takes its time reaching the waldsofa, with the children setting the pace. Frozen raindrops to examine, or muddy hills to slide down, warrant a delay; teachers are mindful of learning opportunities. Singing and laughter abound, but all are serious about safety: There's no running with sticks and no wandering out of sight, among other rules.

The waldsofa is the daily destination and activity hub. Some children help build a fire in the center of the bench area each day, where teachers cook lunch. Students learn that fire duty is an important job requiring great attention to safety. At my son's school, they also use real knives and saws, under close supervision, to sharpen sticks or create play figures. In these ways, the forest kindergarten teaches children the care and skills necessary for safe independence, in turn bolstering their self-confidence.

The curriculum grows out of the ever-changing environment. "The harvest of fruit and nuts allows countless opportunities for learning," says the director of my son's program, Marga Keller, who points to changing weather and blooming plants as among nature's other teachable moments. "Children have a lot of space and time to discover, experiment, and self-direct their learning," she adds. One time, for instance, the students noticed holes in some of the trees. The teachers responded to their curiosity with a discussion on animal homes, hibernation, and habitat.

Keller argues that the forest classroom naturally encourages young children to gain the wide range of skills they'll need in the coming years. Forest kindergartners hone the motor skills the Fribourg study extolled by rolling, climbing, building fires, and making tools, such as stone and stick hammers. The more senses involved in a child's experience, says Keller, the deeper the learning process. And students actively engage all their senses in the forest.

Keller also ascribes psychological benefits to confronting nature, including heightened self-confidence and social competence. Overcoming natural obstacles -- scaling trees, say, or arranging stones to cross streams -- teaches children to trust their abilities. Observing forest life develops their sensitivity, and the wild classroom makes them fundamentally dependent on cooperation. Out of necessity, whether through helping carry a heavy branch or lending a hand to a friend on a slippery hill, students develop trust, interdependence, and respect.

Forest Kindergarten, Stateside

The idea that nature provides a good first classroom is as old as kindergarten itself. Friedrich Froebel, a German educator credited with establishing the first kindergarten around 1840, thought of the outdoors as a natural and obvious classroom for young children, and the success of forest kindergartens in Europe is a testament to that concept.

Yet most American children have little connection to the outdoors, spending their free time plugged into computers, television, and other media instead of outside. Many kindergartens, despite expert opinions that play and inquiry lay the foundation for academic success, have abandoned play for pen and pencil.

"In recent years, too many school districts have turned inward, building windowless schools, banishing live animals from classrooms, and even dropping recess and field trips," notes Richard Louv, author of the influential book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder.

Louv argues that American educators can draw inspiration from Europe's forest kindergartens. "Not everyone has a forest out the back door, but there are often nearby opportunities just as rich in their own way," he says.

Louv details the benefits of spending time in nature: He says kids learn self-confidence. Likewise, hyperactive children improve their focus. Kids playing in nature more often invent their own games and play cooperatively, and they tend to test higher in science.

The idea of U.S. schoolkids being allowed to run around in the rain or snow, use knives, or get near an open fire (much less help build one) is so far removed from standard operating procedure that it can seem almost laughable. Yet outdoor classrooms are sprouting up nationwide, several based on the waldkindergarten model. So far, they're mainly private, early-childhood programs, but their experience can inform public and charter school outdoor-education efforts, too.

One such program was initiated after Davnet Conway Schaffer, an environmental educator with some experience in early-childhood education, read about Europe's forest kindergartens. Schaffer approached the nonprofit nature center where she worked in Mystic, Connecticut, about starting an on-site school based on the waldkindergarten pedagogy. Four years later, the center now houses a private preschool for kids ages 3-5, the Denison Pequotsepos Nature Center Preschool, where Schaffer is director and head teacher.

Into the Woods

According to Schaffer, her students generally spend a minimum of 80 percent of the school day outdoors. The day begins inside, in a converted house reached by a stony path through the nature center's property, where woodpeckers announce their presence and red-tailed hawks cruise overhead. There, morning circle time takes place indoors, but the class soon heads outside for the day's main activities.

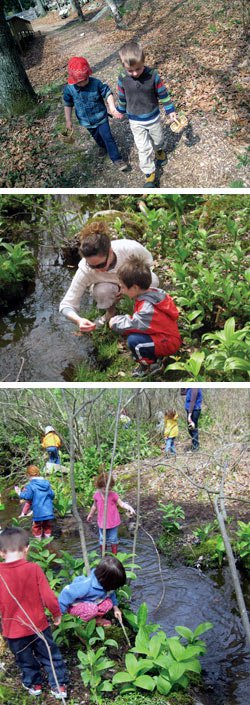

On a recent spring day, the group trekked through the woods to a small stream nearby. As in my son's program, the journey is as much about learning as the destination. "Good morning, friendly bee!" exclaims a five-year-old named Haiden. A group quickly gathers, and the children share their observations about the bee's wings and color. A little farther on, a classmate identifies another treasure: "Skunk cabbage!" The teacher plucks a leaf for the students to smell.

Haiden's mother, Kimberly McKay, expresses delight with the program. "There are no flash cards or worksheets here," she says. "My children don't even realize they are learning; it happens so naturally."

The group is mixed in ages and abilities, and the children help one another navigate natural obstacles such as branches and prickly plants. Schaffer observes more cooperation and fewer altercations during the outdoor portion of the school day. She attributes these attitudes to the lack of man-made stuff -- natural toys are abundant, and children seem less inclined to argue over who had a stone first, for example, than they would over a toy at a conventional sandbox.

After half an hour, the group arrives at the stream. The teacher has distributed baskets for collecting rocks, the current study topic. Eager chatter and laughter erupt as the children venture over a tiny bridge and teeter into the shallow water on rain-booted feet. One little redhead plots her journey "close to the bridge, where the big rocks are."

Contemplating aloud how many treasures will fit into their baskets, the children debate which rock is the shiniest, the flattest, the most heart shaped. When they return to the schoolhouse for the closing portion of the day, they will wash the rocks and continue their observations.

"We have found that it is possible to strike a balance between academic and nature-based learning," says Schaffer, who notes that outside-learning opportunities increase as students get older. "Older children are more able to get involved in team projects, service learning, scientific experiments, and other long-term projects that develop their reading, writing, and mathematical skills in addition to building physical abilities and responsibility."

With healthy enrollment and families devoted to the program, the Dension Pequotsepos preschool is proving successful. It's thriving enough, in fact, that the school is working on plans to expand and add a kindergarten.

As Schaffer's experience bears out, we can transplant some of the ideas of Europe's forest kindergartens onto American soil. If more U.S. educators follow the call of the nature-education movement, perhaps my son's computer-generated snowman can coexist with the real thing in our schools' learning activities.