They Do Call It a “Play,” Don’t They?

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.I was a first-time humanities teacher in a multi-disciplinary, project-based program. My ninth graders were required to study drama, and I selected Euripides' The Trojan Women, as we had already examined parts of the Iliad in connection with another project. My driving question was: "What's the most authentic way for students to engage with a play?" I wanted the students to take the active role in their learning, and to feel free to be creative without worrying about coming up with the right answers to my questions. On the other hand, I wanted to ensure they would be prepared for the expectations of the higher grade levels.

I spoke to one of our theater teachers, R. Kevin Doyle, and asked him how best to accomplish this. His response? "Act it out! Let the students discover the meaning of the text by using their voices and their bodies to explore different meanings." In other words, use what we know about the importance of physical play in learning. It was a phenomenal idea, and fortunately, he offered to facilitate this project with me.

Learning with Our Bodies

We scaffolded the skills we believed the students needed to have in order to be successful with both group performances and individual monologues, as the play is comprised of both elements.

Students should understand how to use their bodies as metaphors, how to project emotion with their voices and, for the history aspect of the curriculum, to think about Euripides' own context and then apply his ideas to the present.

We spent a few days studying actors, poets and other performers, and then developed rubrics to provide clear goals and methods for both peer and self-assessment. Meanwhile, the students read the play on their own and in groups, and selected five scenes that seemed the most interesting to perform. We began with the first scene and asked each student groups to perform a "snapshots" -- essentially, freezing into place. The students not performing used the rubrics to comment on space, posture and even facial expression, but specifically on how to tell the difference between the characters in the scene.

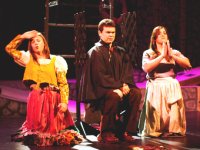

As we added voice and movement, the tasks became more complex. Initially, we wanted the students to move and speak, but found they couldn't do both successfully. We divided the students in each group into actors and readers, and asked them to perform at the same time, letting the actors physically illustrate what the readers were saying. Again, the non-performing groups served as a critical audience, calling attention to the way the three figures presented themselves on stage, the way they held themselves, and questioning the way the lines were read: "What emotion are you trying to convey here? Why these lines? Who is the center of the scene?"

Deepening Our Knowledge

Meanwhile, on non-acting days, students developed driving questions for the history side of the project. These were the basis for their own investigations, the results of which were posted to a class website and then used to help guide the performances. We used Socratic Circles to discuss how to apply some of these ideas to the upcoming scenes, which allowed the groups to plan their performances more effectively. By the time we arrived at the scene where the triumphant Menelaus confronts his wife Helen for the first time while Hecuba watches, the students were able to develop a number of different approaches to play the scene. Based on their history research, which revealed the relative powerlessness of women in ancient Greece, they discussed how Helen was able to subvert that power dynamic by her beauty.

What seemed like a litany of tragic events began to take on a narrative arc, as we watched Hecuba lose pieces of her world in ascending levels of horror -- first, the loss of a family member, then the loss of the gods, the loss of the hope for justice, and finally, with the murder of Hector's son, the loss of the future.

We had three final assessments for the project -- a group performance, an essay and a monologue. Again, we followed the same procedure:

- Modeling by example

- Developing a rubric

- Offering multiple iterations and opportunities for peer and self-critique

- Posting their final version to YouTube

Creativity and Transformation

I found that, for the most part, students had achieved as much understanding from that four-week project as they would have done from a series of more traditional classroom activities. The larger point is that much of the knowledge was discovered by their own efforts, and they had developed numerous other ways of showing me what they had learned beyond simply writing.

The students’ final feedback on this project was that it was awkward at first, but once they got used to performing and found their interest in the material, their comprehension of it had increased dramatically. More importantly, however, I found my own teaching transformed by incorporating the artistic process into my classroom. The students learned by doing, and felt free to improvise, to create, to think far outside the box, and even to change the way the project was facilitated -- if not the nature of the final product itself -- as their needs changed.

Have you used drama as an element of PBL? Please share your experiences below.