Winning at Any Cost: How Nashville Is Retraining Top-Tier Youth Athletic Coaches

Generations of student athletes have endured harsh, humiliating coaching practices. Now a large urban school district is seeking to break that cycle—and keep winning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Strict, militaristic discipline and authoritarian power with frequent outbursts of screaming and cursing: That’s how Seth Massey remembers basketball coaches getting the best out of student athletes when he was a player in high school and college. Their role models were legendary coaches like Bobby Knight and Bear Bryant—famous for their winning records, and also infamous for a training style you might call coaching by intimidation.

Once Massey became a high school teacher and basketball coach in Sumner County, Tennessee, he found himself falling into similar patterns. While he didn’t cross the line into abusive practices, he says, his attitude was similar: Winning was the goal that justified the means. “Sometimes I could get so driven to win, kids were just pawns in the game,” he recalled. “All I needed them to do was x-y-z on the court.”

That began to change three years ago when he met Scott Hearon, another former athlete turned coach, who started an organization for Tennessee coaches, hoping to address what he saw as an urgent problem in youth sports: the focus on winning at all costs. The group, known as the Nashville Coaching Coalition (NCC), included local coaches who met once a week for professional growth—but not the kind you’d get at typical professional development sessions.

“It’s kind of like therapy for coaches,” Massey said in his deadpan Southern drawl. “It changed me a lot. You make sense of your story so you can help others with theirs. You start to see people as people, instead of just players.”

Massey’s story isn’t unusual. Generations of student athletes have endured tough, humiliating, sometimes abusive coaching practices in middle and high school, usually at the hands of coaches who themselves endured the same practices as students. And even those who didn’t face humiliation often describe an atmosphere where their self-worth was entirely wrapped up in their performance on the field or the court.

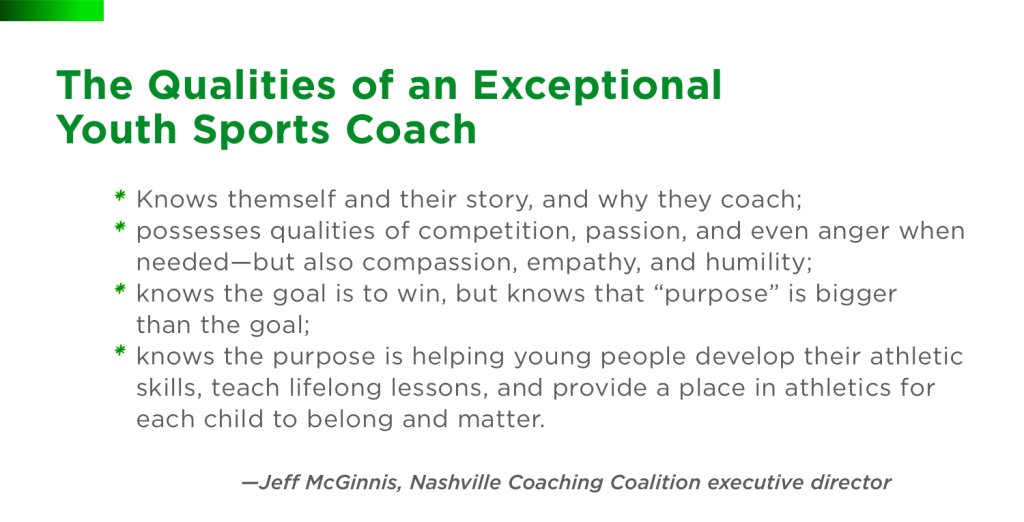

NCC—which this year signed a five-year contract to provide mandatory training to all middle and high school youth athletic coaches in the Metro Nashville Public Schools district—is part of a new effort to break that cycle and transform how coaches form relationships with players, how they define success, and how they ultimately keep winning. Winning, of course, is always the goal, and tough, direct feedback will always be part of improving team outcomes, but groups like NCC say that how teams get there is as important as the numbers on the scoreboard.

This shift comes alongside national conversations about the teen mental health crisis and the debilitating pressure of youth sports on student athletes. Increasingly, young athletes are speaking out, calling out practices that push them “to the edge by relentless pressure.” Professional athletes like Simone Biles and Michael Phelps have made public their own struggles with mental health and performance pressure, while popular shows like Ted Lasso portray vulnerable coaches seeking to give players a more humane, meaningful experience in sports.

“Coaches play a terribly important role in kids’ lives,” said journalist Linda Flanagan, former cross-country coach and author of Take Back the Game: How Money and Mania Are Ruining Kids’ Sports—and Why It Matters. Coaches spend a lot of time with the 60 million kids and teens who play sports each year, sometimes more than any other adult in their lives, Flanagan said, and what happens in that time bears huge consequences on kids’ lives. “Sports are emotional, and as a coach you are witness to that, you are an adult helping young players navigate strong feelings. You have influence over them, for better or worse.”

Getting at the Why of Coaching

On a recent Wednesday evening, nearly 100 Metro Nashville Public Schools high school coaches filed into a large conference room for the second of three sessions of the NCC Leadership Academy. Through workshops and small group discussions, coaches enrolled in this required program “learn the tools needed to ensure that their players are prepared for life, not just the game,” according to the NCC website. Based on the coaching philosophy of former NFL defensive lineman and Syracuse All-American Joe Ehrmann, NCC’s programming leads coaches through a series of exercises meant to highlight why they got into sports and coaching in the first place, followed by concrete steps for how to make those same motivations—helping players feel valuable as people, growth in skills instead of purely performance—the center of their current teams. The idea is to move coaches from a “transactional” sports model to one that’s “transformational,” said current NCC executive director Jeff McGinnis.

“Children can be diminished and discouraged by their sports experience, or they can be strengthened, uplifted, and even in some cases redeemed,” Ehrmann wrote in his popular book InSideOut Coaching: How Sports Can Transform Lives. “Sports can be a life-changing experience if coaches understand why they are coaching and redefine their measurement of success.”

Redefining sports success was a top priority for NCC founders, father and son Randy and Scott Hearon, when they launched it with a handful of coaches seven years ago. For them, transforming coaching was personal—both recall how their family’s obsession with sports competition and winning brought them together, but also caused friction and sometimes pain. So competencies like relationship skills and self-awareness are woven into the curriculum and seem to be a natural fit for the emotion inherent in competitive sports. Scott describes playing sports as “a superhighway to the subconscious,” a powerful and direct way to reveal important aspects of your deepest self and values.

At the meeting, coaches pass around a microphone, sharing their big relational wins for the week: One coach talks about guiding a player to be more respectful without having to use harsh punishment; another shares how hard it is to cut a tearful 15-year-old from his women’s softball team, but he’s finding better ways to communicate with them.

Most student athletes leave sports altogether by age 11, many saying, “It’s just not fun anymore,” and experts say a big reason for that is that most youth sports coaches receive little or no training in child development. Coaches mainly rely on their most recent sports experience (usually high school or college sports) and don’t know there are different developmentally appropriate ways to work with and motivate elementary-aged children compared with high school students, for example. The idea that “sports teach character” is often touted, said Flanagan, the coach and journalist. That’s true only if adults involved think carefully about how to teach the hard lessons like sportsmanship, collaboration, and resilience, in age-appropriate ways and often under great external pressure to win a game, a playoff, or a championship. Winning remains paramount, but finding the right balance among all the other important values takes training.

“There’s this weird carve-out for sports, where behavior that is verboten elsewhere is tolerated on the field,” Flanagan said. “The best coaches are those who connect with the kids, are positive, and have high expectations and standards. But you have to model it, model this behavior yourself.”

Making Room for Student Feedback

As the evening progresses, Metro Nashville coaches break into small groups led by counselors. Sharing past and present experiences, they address four key questions:

- Why do I coach?

- Why do I coach the way that I do?

- What does it feel like to be coached by me?

- How do I define success?

Randy Hearon said the small group sessions are the heart of NCC; coaches who are often siloed and isolated within their schools get a chance to form a community and share their experiences with other coaches. In their small groups, coaches get opportunities to reveal positive and negative emotional experiences they have had with sports, some going all the way back to childhood.

One question that night stood out for Secret Woode, the volleyball coach at Antioch High School: “What does it feel like to be coached by me?” She often wondered how students would answer that, but until NCC she hadn’t thought to ask. Next season, she’s implementing monthly feedback sessions, where players can give feedback about their experiences.

“It’s a humbling thing to have them answer,” Woode said. “But I’ll have them put that on paper; that will help a lot. Feedback is a good thing to ask for.”

Others were more concerned about the high-wire act of broadening the meaning of sports success without giving up the passionate desire to win the game. Experts say that investing in student well-being doesn’t mean teams stop having high expectations of players—in fact, research shows that students who feel good about themselves and are connected to their team perform better.

Coaches like Scott Davis, a football coach at Hillsboro High School, see the arrival of a “kinder, gentler” sports environment as a welcome change. “It used to be that hollering and cussing at your players was considered good coaching,” he said. “This more holistic type of coaching is good. The kids feel more empowered—you can motivate them by getting in tune with them. You can build relationships on a deeper level than just ‘show up and play.’”

Fundamentally, mental wellness is essential for high-level performance, notes Jessica Kirby, a sports psychologist at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. “If you are exhausted, overtrained, or afraid of your coach, you are not at your highest capacity,” she said. “Your performance might be good, but it’s not as good as it could be if you were in excellent mental health.”