Why Sex Education Isn’t Just About Biology Anymore

We talked to science teachers and health educators across the country to better understand how sex ed has evolved to adapt to our increasingly complex sociopolitical climate.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Melyssa Ferro knew she had to teach sex education soon after she began working as a middle school science teacher in Idaho’s Caldwell School District. “That was a really important issue for the students in my district to have some information on because at that time, our teen pregnancy rates in the district were fairly significant,” Ferro says. “I was actually pregnant with my third child at the same time as two students in my class.”

Now, more than two decades later, Ferro is still passionate about creating a safe environment for students during the annual sex education week in her district. In Idaho, where the standard remains abstinence-based sex education, and parents in her district have to opt in each year to allow their kids to receive sex ed in schools, it isn’t easy to carve out time or space to have broad conversations around sex education.

But the internet provides students with unfettered access to sprawling social movements like #MeToo, opening up new opportunities—and new expectations—for when, where, and how they discuss issues of consent and healthy relationships even as our society as a whole grows rapidly more conscious of gender and sexual fluidity.

“There’s a lot more that goes into sex than just biology,” says Ferro. “There’s the physical, the intellectual, the emotional and social aspects.”

This more holistic understanding of sex ed, encompassing crucial aspects of human sexuality beyond anatomy and biology, is the foundation of comprehensive sex education (CSE) in schools. Such instruction entails scientifically accurate information about human development and reproductive health, as well as information about contraception and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health reviewing literature dating back to 1990 revealed that school-based CSE improved students’ understanding of healthy relationships and gender norms, ultimately reducing “homophobia and homophobic-related bullying” and “dating and intimate partner violence.”

We talked to science teachers and health educators across the country to better understand how sex ed has evolved to adapt to our increasingly complex sociopolitical climate.

Contested Ground

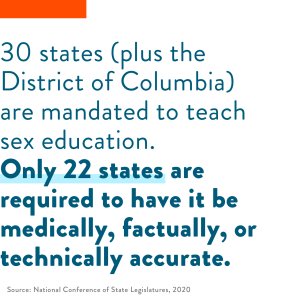

Sex ed has long been a controversial topic, but when schools do address it in their curriculum, the information given to students isn’t always based on scientific facts. As of 2020, the National Conference of State Legislatures reports, public schools in 30 states and the District of Columbia were mandated to teach sex education, and just 22 states required that if provided, sex education must be “medically, factually or technically accurate.”

On the other hand, 19 states, including Arizona, Utah, Louisiana, Michigan, and Texas, are still stressing that only abstinence should be taught in schools. Proponents of abstinence-focused education say that they are concerned about whether it’s appropriate for students to be thinking about sex before marriage—a popular sentiment among families who disapprove of premarital sex because of their religious beliefs or moral values. Many emphasize the idea that abstinence is a simple yet effective way to prevent pregnancies as well as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and that sex ed that decenters abstinence would encourage sexual activity in young students.

This is a common mindset among skeptics who do not support comprehensive sex ed, says Meredith Byars, a media specialist at Magic Acceptance Academy in Homewood, Alabama. “So the goal of CSE that is very misunderstood—it is to provide age-appropriate, scientifically accurate information,” says Byars, a trans and nonbinary health educator who has done research on the trans and intersex (those born with a sexual anatomy that doesn’t fit the typical definitions of female or male) communities. “And a lot of people that oppose CSE assume that it will promote sexual activity for youth or encourage kids to become trans, and there’s actually no structural or empirical evidence of that.”

In fact, there’s ample research showing that abstinence-only programs neither succeed in reducing rates of teen pregnancies or STDs nor help adolescents delay having intercourse. Moreover, a 2022 study that investigated the long-term impact of CSE programs in 55 U.S. counties shows that there was a decline in teen births after they received federal funding from the Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) program—teen pregnancy rates dropped by an average reduction of over 3 percent during the 20-year period.

Going Beyond Biology

In Ferro’s seventh-grade science classroom, sex ed fits neatly into the science curriculum: It does begin with biology. “We talk about cells, we talk about genetics and DNA, we talk about systems and how body systems function,” she says. “And so it kind of made a nice capstone week for us to go in and talk about reproductive systems.”

Given that inclusive sex ed is still contentious in Idaho, Ferro says she primarily sticks to the biology of sex when teaching sex ed, but she has found ways to frame conversations about the social and emotional aspects without being judgmental or trying to tell students what’s right and wrong. “When you get ready to use your body parts, because you’re going to use them at some point, I want you to be able to make the best decisions for you,” she says. “You know your family values, you know your family morals, you know your religious convictions. Let me give you the knowledge that you need to make the best decisions possible with your body.”

To educators like Deborah Roffman, who calls herself a human sexuality educator—not a sex educator—the subject has never been merely about sexual behavior, and therefore the language we use when talking about sex education is also flawed.

“What we tend to do in this culture is take this huge part of life and keep narrowing it down until we get to intercourse,” says Roffman, who has taught sexuality education to young people of all ages since 1971. “It’s really not just about the body parts, it’s about the human being attached to the body parts. And if you think deeply enough about it, sexuality is the essential life force, you know? So why wouldn’t it be connected to everything?”

Information about how sex works from an anatomical perspective will not prepare students for real-life scenarios where they need to make informed decisions about what they want or do not want to do, health educators tell us—and this is where lessons about consent come in.

“Consent education in and of itself does not have to be about hookup culture or premarital sex,” says Laura McGuire, a Florida-based sexuality educator and former middle and high school teacher. And regardless of religious values, McGuire explains, students will need to know about consent because “even when they get married, right, don’t you want them to have this foundation of what it means to interact with the other person intimately?”

Honoring Students’ Diverse Sexualities

Human sexuality is everything “connected meaningfully to issues of sex, gender, and reproduction,” says Roffman. She stresses that the common discourse around sex is still very limited because “if we think about the way we define the word sex still as penis and vagina, look what that says to gay kids: ‘All right. You don’t exist, you don’t have sex, you don’t have sexuality.’”

For teachers like McGuire and Byars who live in states like Florida and Alabama that recently passed laws that would ban discussion around sexual orientation and gender—and restrict health care for trans youth—implementing an inclusive and comprehensive sex ed curriculum is one way they say they’re showing up for their marginalized students, especially trans students, to help them feel safe and included.

Geoffrey Carlisle, a middle school science teacher in Austin, Texas, says he was motivated to teach sex ed partly because of his “damaging experience” with the subject. “The first time a teacher ever acknowledged that queer people like me existed was when my eighth-grade health science teacher said that gay men are the ones who get HIV and it’s fatal,” says Carlisle. “Then she just moved on, and I never had another teacher talk about LGBTQ+ people until I was in college.”

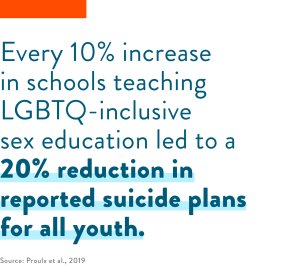

Failing to recognize diverse sexualities drives up rates of depression, leaves the door open to bullying and violence, and leads to higher rates of dropping out and suicide in the LGBTQ+ community, according to a 2021 survey by the Trevor Project. With those statistics in mind, Carlisle’s first priority is to create a learning environment where students across gender, sex, and sexuality spectrums feel seen and valued. “A pitfall that some curriculums fall into is only presenting relationships or individuals in these curriculums as cisgender and heterosexual,” he says.

In fact, behavioral and community health researchers who studied sex ed programs in 11 states found that when students had access to LGBTQ+ inclusive sex ed programs, there were fewer reports of homophobia-related bullying—and more positive mental health outcomes for all students on campus.

Today, it’s more important than ever to provide sex ed that addresses diverse genders and sexualities, as this generation has the highest rates of LGBTQ+ identity, McGuire says. “Our students are smart enough with the advent of the internet that they can connect with each other and educate each other and say to educators, ‘Wait a minute, this is not OK. This is not including my experience.’”

It is an enormous responsibility to teach inclusive sex ed when there’s a lack of support from state legislators, but Byars hopes teachers will not give up and will continue to advocate for their students, making sure that if they’re not protected elsewhere, they’re safe in the classroom. “This anti-trans legislation that Alabama is facing right now [which would criminalize offering hormone treatments to trans youth]—it’s worse than it was when I was growing up as a trans, nonbinary, and intersex child. And the best thing I can do from my perspective is be an advocate and an ally for them.”