Using Street Art to Explore Hispanic Heritage

Delving into street art can fuel conversations and learning about Hispanic and Latino culture, heritage, and identity in creative and unexpected ways.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Finding time to observe heritage months in the midst of a full teaching calendar can be a challenge. I like to think of these celebrations as a starting point: While a culturally proficient pedagogy threads the contributions and social context of historically marginalized communities into lessons throughout the school year, we can also capitalize on the special focus these months provide to build our own knowledge and toolbox of resources so that we can weave them into our content in ways that go beyond the time limits imposed by the calendar.

National Hispanic Heritage Month stretches from mid-September to mid-October, and the historical, scientific, artistic, and cultural contributions that this month showcases are plentiful. An exciting place to dig in is with public art, which is, by definition, shared art, making it uniquely accessible and interesting to students. Public art is meant to speak for and to the community it inhabits; it aims to beautify and define or redefine public spaces. It may even serve to provoke dissent or protest. And it commemorates: Creating art to remember and honor the dead is a pillar of Latino culture and a powerful way to help students process difficult experiences. Murals like After the Final Lakers Game, by Los Angeles art teacher and artist Melany Meza-Dierks, for example, provide space for a community to grieve and remember.

Some of the first, oldest, and most historically significant art is public art. Within the category, murals are public art applied to a wall or a ceiling. They often highlight a particular relationship to a space and pose historical or political questions about it. A distant cousin to murals, graffiti refers to images or writing (usually spray-painted) on a wall or building. While graffiti is also meant to be publicly seen, it can raise issues around legality and economics—rich fodder for classroom discussions or persuasive writing exercises about who gets to define and control the expression of artistic impulses.

Street Artists to Explore in the Classroom

With the goal of teaching about Hispanic and Latino culture and history in unexpected and engaging ways, here are a few fresh, imaginative, and disruptive artists who are resoundingly, proudly Latino. Their work is extremely accessible, freely available on websites and social media accounts that teachers and students can easily tap into to investigate the lives, influences, and cultural contexts of each artist. It can be used to unpack themes of marginalization, body autonomy, and personal power and agency; collectively, their oeuvres deal with transcending social constraints, projecting diverse ideas of beauty, and expressing the desire to belong—themes that middle and high school students can connect with in deeply creative ways.

Stinkfish is a Colombian street artist who makes vivid patterned images, frequently of children’s faces, that are displayed in high-traffic areas of cities all over the world. He is also known as the Colombian Wanderer, following a long line of Latino artists who address issues of identity and immigration, migration and borders in their work. Stinkfish’s paintings make us think about identity, noise, energy, and movement. Students will connect with the origin story: As a child, he tagged his notebooks, desks, and every surface in sight. His technique of layering stencils of patterns and colors to create faces and stories is easy to explore and make your own. If you’re creating cards or decorations for holidays or gifts, for example, have students create a set of classroom stencils and then use them to try out the artist’s technique of layering colors and shapes.

If Stinkfish is more the mysterious, rebel graffiti artist, Argentinean artist Zosen Bandido is a teacher’s street artist if there ever was one. He works with media including video, illustration, installation, and paintings that are at once traditional and immediate. His work tells complicated stories, frequently incorporating text and geometric symbols and devices. Calling to mind Indigenous pictorial writing systems or the designs of Indigenous art practices like Mexican Otomi embroidery, Bandido developed his own powerful and unique visual language, suggesting new ways to experience art and tell stories.

Using the art of Bandido as a starting point—or, for younger students, Argentinean artist Sonni uses a similarly conceptually complex approach but with more accessible visual elements—have students create their own classroom mural. They can draw inspiration from how these artists use straightforward techniques to communicate complex messages about themselves and the cultures they’re steeped in.

Rimon Guimarães is a Brazilian born, Afro-Latino mural artist who creates his dreamy, absorbing images through paint, photography, and digital media. Similar to the work of the original most recognizable and important muralist Diego Rivera, this colorful work elevates the everyday and builds on the theme of complex Latino identity by incorporating a vocabulary of African diasporic symbols and color stories. His work is grand and romantic, challenging his audience to experience the magic of the ordinary. In class, you might pivot off of Guimarães’s images to get your students thinking about character and character development in a text you’re reading together. Have students practice visual thinking by first observing the artist’s work and then imagining who these people are and what their backstories could be.

Caro Pepe is an Argentinean street artist who works in Berlin and has a distinct visual mark: She uses the image of one-eyed women to tell a range of stories. Rather than go wide, Pepe goes deep by creating public art that is extremely personal. There is a good chance your students will be familiar with the work of Frida Kahlo; the work of Caro Pepe investigates many of the same themes—identity, death, the human body—but her work gives us a fresh approach. By tapping into prior knowledge of Kahlo’s work and comparing with to Pepe’s, students might use some of their images as a prompt for a journal jot or more structured writing assignment examining the complex themes of body image and autonomy.

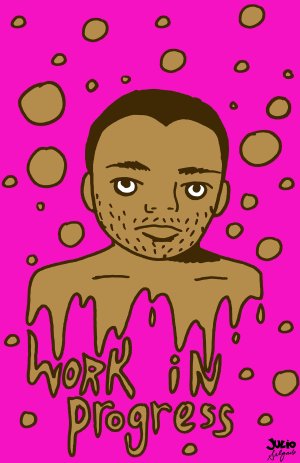

“I was always the kid drawing at the back of the [class]room,” says Julio Salgado in a short video about his work. Salgado is a Mexican digital artist and activist who grew up in Long Beach, California, and whose work—murals, fliers, and shareable graphics currently featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum—aims to support and empower the queer and undocumented LatinX community. Echoing the work of other significant Mexican artists, including José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar, who created satirical, accessible illustrations that challenged oppressive systems using a demotic visual language, Salgado’s work shows us how art can be a powerful tool for social justice. His activism on behalf of marginalized communities is inspiring, but students will likely relate to how a younger Salgado connected to classmates through art, drawing their names in “cool letters” or sketching their likeness in class, he recalls. Inspired by the idea, try pairing students up with classmates they’re not usually paired with, and ask them to either draw each other’s names or sketch a quick portrait of each other, just as Salgado did to make friends as a kid.