Using Hands-On History Projects to Bring Unheard Voices to Life

Creating with ancient tools gives students a greater appreciation for the people who used this technology in the past.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.My Roman technology students re-create the products, processes, and stories of ancient Roman life through experimental archaeology. We make the things that Romans used with their tools and methods. Through this hands-on history, we experience the lives of people who do not have a voice in classical literature— women, children, craftspeople, and the enslaved people among them. Stepping into the “sandals” of these Roman people gives students a unique understanding of ancient daily life.

Only a sliver of the past was recorded for us to read today. We must guess what life was like for those who had no voice in that written history. Ancient Roman architect Vitruvius wrote about building mosaics, but he didn’t describe the tiredness of the arm after a long day of wielding a heavy stonecutting hammer, nor the smell of mortar and its effect on the lungs after daily exposure.

In one unit of study, my students learned how to cut stone using hammers and hardies, metal wedges for cracking stone into tiny pieces called tesserae. We practiced cutting different types of stone to create the many colors necessary for complex Roman mosaics. Then, after cutting hundreds of tesserae, students fit them together to build a large analemmatic sundial, which uses the viewer’s shadow to indicate the time. The process of building this structure was long and sometimes tedious, but it gave my students an intricate look into the lives of ancient stonecutters.

One day during a long stonecutting session, I looked up to see a cloud of stone dust hovering over my students’ heads near the classroom ceiling. Suddenly, the hammer in my hand felt different. I was taken back to an ancient Roman stonecutting workshop where laborers breathed that dust continuously during many years of hard work. Thankfully for us, we were able to move our stonecutting operation outdoors where the dust was not a health hazard.

Opening A Window Into the Past

As we worked, we discovered that the interactions that naturally arose between stonecutters and mosaic builders lent themselves to cutting the stone where the mosaic was being created.

Some students acted as the stonecutters, or the lapidarii structores. Others acted as the tessellarii, placing cut stone pieces into mortar to make the images. As the mosaic began to take shape, inevitably one would need a stone shape we hadn’t yet cut. The tessellarii would call out, “Small green triangle,” and the lapidarii structores would cut and deliver it immediately. We never would have understood this process as well as we did had we only read about it.

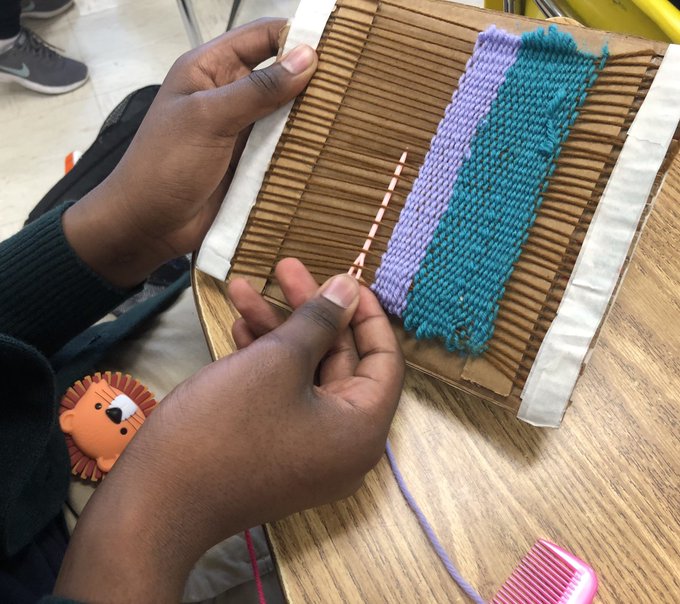

In a unit centered on creating fiber, students learned how to process and dye raw wool, comb it into usable fiber, spin it, and then weave it into small pieces of cloth. This weaving unit remains a favorite because students found it “fun.”

Despite the tedious and monotonous work, we enjoyed sitting around a large classroom table, weaving and discussing our lives. You may notice that I’ve used the word “we” a lot to describe our work. I end up being involved in the projects as a craftsperson too, and through those collaborations I have learned about my students more personally than I might have otherwise done. Busy hands make for revealing conversations.

It was on one such weaving day that I found out why a student had a cut on his face. A man in a park had attacked him while he was swinging with his younger brother. Through the student sharing this terrible experience, he and I developed a deeper connection. During the next week, the student asked me to sit with him while he received his immunization shots. (His mother could not be present due to work.) Hands-on history allows for so much sharing and togetherness not found in a more traditional classroom.

Did ancient weavers share the same connections? Did they chat about their lives as they worked? My students have always come away from our weaving lessons with not only a deeper appreciation for the effort behind cloth making but also a deeper connection to their classmates and teacher.

My students have done many other similar projects: hairstyling; processing grain; building bread ovens; record keeping with papyrus, squid ink, and wax tablets; bathing with strigils, oil, and sand; and many others. Some projects do have equipment costs that likely need grant dollars. A national grant and some local building companies paid for the mosaic project.

Many other Roman technology units, however, are well within a school’s equipment budget with some creative anachronism. The weaving project was inexpensive. We used recycled cardboard to create the looms and donated yarn from local crochet and knitting enthusiasts. The only things we bought were cheap plastic sewing needles to use as shuttles on our mini-looms. In addition, the weaving unit could be adapted to any time period and culture.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to cost concerns, teachers should take care to consider the ethical questions that arise from bringing to life a time when mores were far different from today’s. Some work done by ancient people, particularly the enslaved, should not be reproduced due to health concerns or the risk of causing trauma. For example, we would never ask students to step into urine-filled vats to clean cloth. Such projects cross a line that should never be crossed.

Re-creating the past should be educational, fun, and safe. Students should reproduce ancient products and processes that give them a richer understanding of the dignity and pride of the hard work done by people of the past.

As teachers, we have the power to bring the unheard voices of history to life through the everyday objects that people owned and used. We gain a much deeper appreciation for those unheard voices through experimental archaeology.