A Culturally Responsive Approach to Teaching the Alphabet

Students get excited about phonics when educators teach the alphabet alongside art, citizenship, and explorations of culture.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.From a young age, I witnessed that reading was never just about learning to decode, that culturally responsive teaching was a necessary part of literacy. My mom is a teacher, and some of my earliest memories are of sitting in the back of her classrooms—not in typical K–12 schools, but on orange and olive ranches in California, where she taught migrant farmworkers; at adult learning centers in New England mill towns where adults spent night classes learning how to fill out job applications; and in makeshift buildings on sugarcane farms in northeastern Brazil, where my mother taught workers while studying and utilizing Paulo Freire’s teaching methods.

She had few classroom materials and used what she could, as prescribed by Freire: photographs of daily life, realia, and word lists reflective of and generated by her students to cocreate mutual understanding, joy, and urgency around becoming literate.

I internalized all of this, so it was no surprise that I became a reading specialist. Yet, in recent years, I’ve been struggling to find ways to make foundational reading skills—alphabetic principles and phonemic awareness—more relevant, interesting, and integrated into my end goals for student literacy: participatory citizenship, critical consciousness, and reading the world.

A SPARK OF INSPIRATION

In 2022, I sat in my office sipping my morning coffee. Our school had just returned from spring break, and my colleague Kate Surmeier, the school counselor, knocked on my door. “Can I show you something?” she asked. Kate had gone to New York for spring break. She pulled out her phone and began to tell me about this amazing artist’s exhibit she had attended. Enter the Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré.

Kate had taken pictures of the exhibit Knowledge of the World, and she began telling me how the artwork mesmerized her: hundreds of images, a visual syllabary, documented Bété language and culture, all on cardboard rectangles from recycled hair care boxes. She told me that as she sat there taking it all in, she was reminded of the letter-keyword alphabet cards she’d seen me use with my students.

“Couldn’t we collaborate and do a project around phonemic awareness and identity and building classroom community, making our own cards?” Kate asked. The “Our Alphabet” project was born.

DIVING INTO IDENTITY

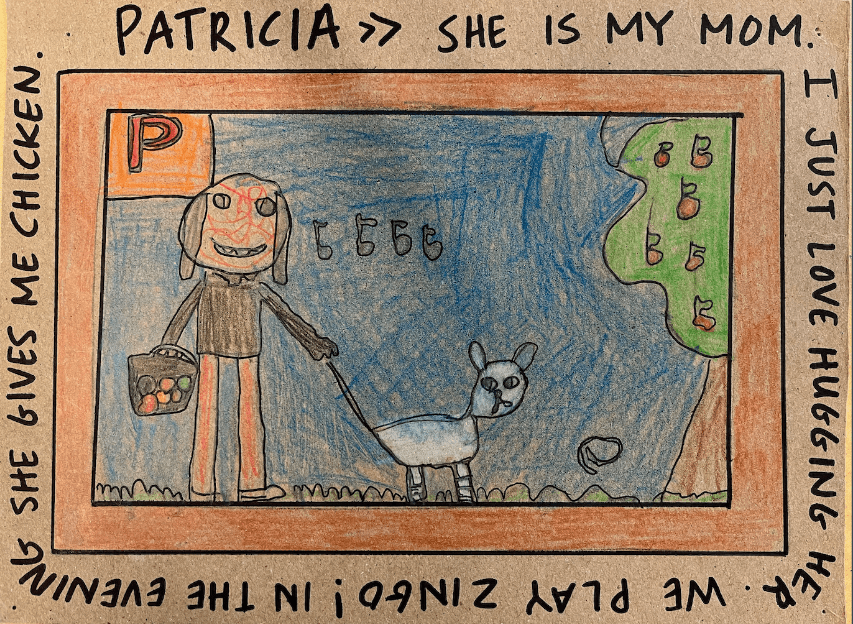

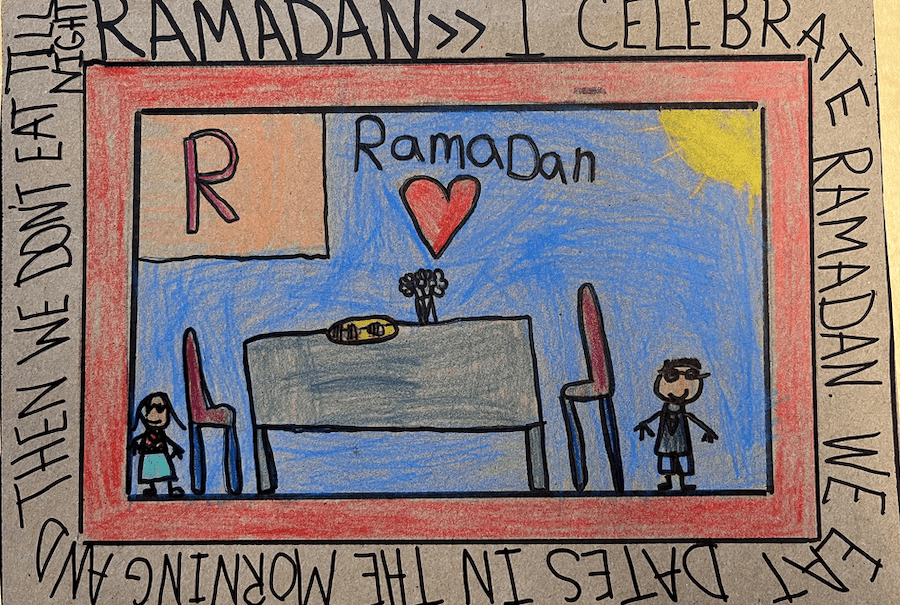

In “Our Alphabet,” we made our own letter keyword cards, inspired by Bouabré’s work, on recycled cardboard, with student-generated keywords.

Our project had three components: identity work, knowledge-building, and literacy. We began with identity. Kate built upon the CASEL Framework for social and emotional learning by going into classrooms and reading various children’s books about identity and community. Her goals for these discussions were to help students deepen pride in their identities while developing cross-cultural understanding.

Kate has observed that young children often default to social connections rooted in sameness and wanted to create opportunities to find connections within differences. In addition, because we start formal reading instruction in first grade, there can be student anxiety about learning how to read. Kate felt that starting with art and infusing creativity into the process would reduce some pressure, and her instincts were right: Students generated their own keywords, confidently shared why these words were important to them, and celebrated similarities and differences within their classroom communities.

BUILDING KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge-building was another critical piece of the project. Recent research shows that direct instruction of academic knowledge is largely missing from reading comprehension curricula, constituting what Natalie Wexler termed “the knowledge gap.”

We also wanted to build students’ knowledge about our inspiration, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. We began by looking at his art and examining a world map, locating the Ivory Coast. We looked at pictures of the country (rural, coastal, and urban areas) and listened to the Bété language. We discussed colonization and the relationship between power and language.

From there, the conversation segued into why Bouabré wanted to record Bété into written form. It was shocking (and wonderful!) how easily our first graders grasped these abstract and political concepts. Some memorable observations by first graders included “They want to keep their own language” and “We need to write important things down so we don’t forget.”

PHONICS

Lastly, we worked on phonics and generating letter-keyword relationships. We talked about the identity work that Kate did with students and Bouabré’s alphabet cards. We wondered aloud: Might we make our own alphabet cards that reflect our community and daily lives? Students offered an emphatic “Yes!”

To stay true to our Bouabré-inspired concept, we enlisted parents to share recycled cardboard cereal boxes and committed to using only pens and colored pencils. We also used his design of a visual image inside a border with surrounding text describing the image.

We assigned each student and teacher a letter to contribute—a process that generated palpable excitement. There were offers to trade letters, audible cheers, and immediate idea generation among students: “What letter did you get?” and “How about Noodles for N—you always bring them for lunch!”

In the end, we created an alphabet for each of our six first-grade classrooms. We also enlisted faculty and staff to make their own alphabet, and we exhibited pictures of the finished project.

I’ve been a reading teacher for almost 30 years, and I’ve never heard such excitement and organic conversation among children around letter sounds. It was music to my ears—and had achieved everything that I thought had been missing; phonics had become relevant, interesting, and participatory, indicating that this replicable project holds the power to foster meaningful engagement.

The author would like to thank Kate Surmeier for her contributions to this project.