Fostering Time Management Skills With Young Students

Helping early elementary students develop their sense of time can have a major impact on their academic and social skills.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.As teachers, we see and know how crucial time management is for student success. Time management is a crucial skill that is a prerequisite for future academic achievement at both the collegiate and career levels. Students with effective time management skills tend to have lower levels of stress and anxiety, have more self-control, and develop stronger study habits.

Time management for children

When we think about what successful time management looks like, we can picture a combination of skills: internal estimation of time, prioritization of time, coping with time constraints, and balancing the time demands of certain activities. Laying the groundwork for effective time management starts in elementary school and requires explicit and consistent practice in order for students to meet the demands and flourish in secondary education. Receiving this instruction at a younger age allows students to internalize and develop a framework on how best to manage their time in order to cater to their needs, wants, and ultimately desired successes in and outside of school.

For students to develop this skill, teachers can look at time management as a muscle that needs daily attention and practice. I call this “muscle” the internal body clock. It teaches students that time management is a muscle in their body where they can feel and estimate time more efficiently. Teaching students how to use their internal body clock helps them become more successful with managing their time to plan to break down tasks to complete larger tasks, stay organized, avoid procrastinating, and balance their responsibilities. In the classroom, this correlates with greater academic achievement for students, teachers being able to optimize time, increasing focus and motivation around a task or goal, and reducing anxiety.

Building the Internal Body Clock

To build a child’s internal body clock, I begin with an activity where students feel time in their bodies for 60 seconds.

Round one: I ask them to raise their hand when they think 60 seconds are up. This activity is easy for most students, as most are focused on counting seconds so they get closer to the minute mark. As a class, we discussed what it felt like and the strategies they used to gauge that 60 seconds had passed. Students reflected that they had to focus only on counting and not getting distracted. This step is important, as it embeds the practice of reflecting on how we use our time, which becomes a crucial part of building the internal body clock. We also discuss how our internal body clock is not a precise clock, and having strong time estimation capability can vary within 50–70 seconds.

Round two: I repeat this same activity but layer in distractions. During the second iteration of the exercise, I provide the same directions and ask students to do a moderately easy assignment. I notice that students struggle to accurately determine when a minute is up while still doing the task. Examples of this could be practicing spelling words, organizing a desk, completing a routine, or finishing classwork. Typically, some students forget about the concept of time and focus only on the assignment, while others only focus on counting and do not complete or make progress with the assignment. During this time, they either under- or overshoot a minute.

We then reflect on how hard time estimation is. Students tend to identify two things: First, it can be easy to lose track of time when doing an assignment, and second, it can be easier to procrastinate when we watch the time go by without completing a task. Many students report that time seems to move more slowly when they are doing a less preferred activity.

Round three: Finally, I have students again raise their hand once they feel a minute has passed, but this time they are engaged in a fun activity like a game. Most students forget to raise their hand when they feel like a minute has passed. They typically remember to raise their hand after three or more minutes or when I remind them. This teaches students that time seems to go by fast when we are doing engaging or preferred tasks.

Discussion: I ask the class to brainstorm tasks that we know take a minute, such as washing their hands or unpacking a book bag. From there they discuss other common tasks and estimate the time they take, like packing their bag, getting dressed, or showering. This helps anchor time estimation within common routines. While some students may differ on how long it takes to get ready or shower, it leads to conversation about how some people recognize that they need more or less time for something and plan accordingly.

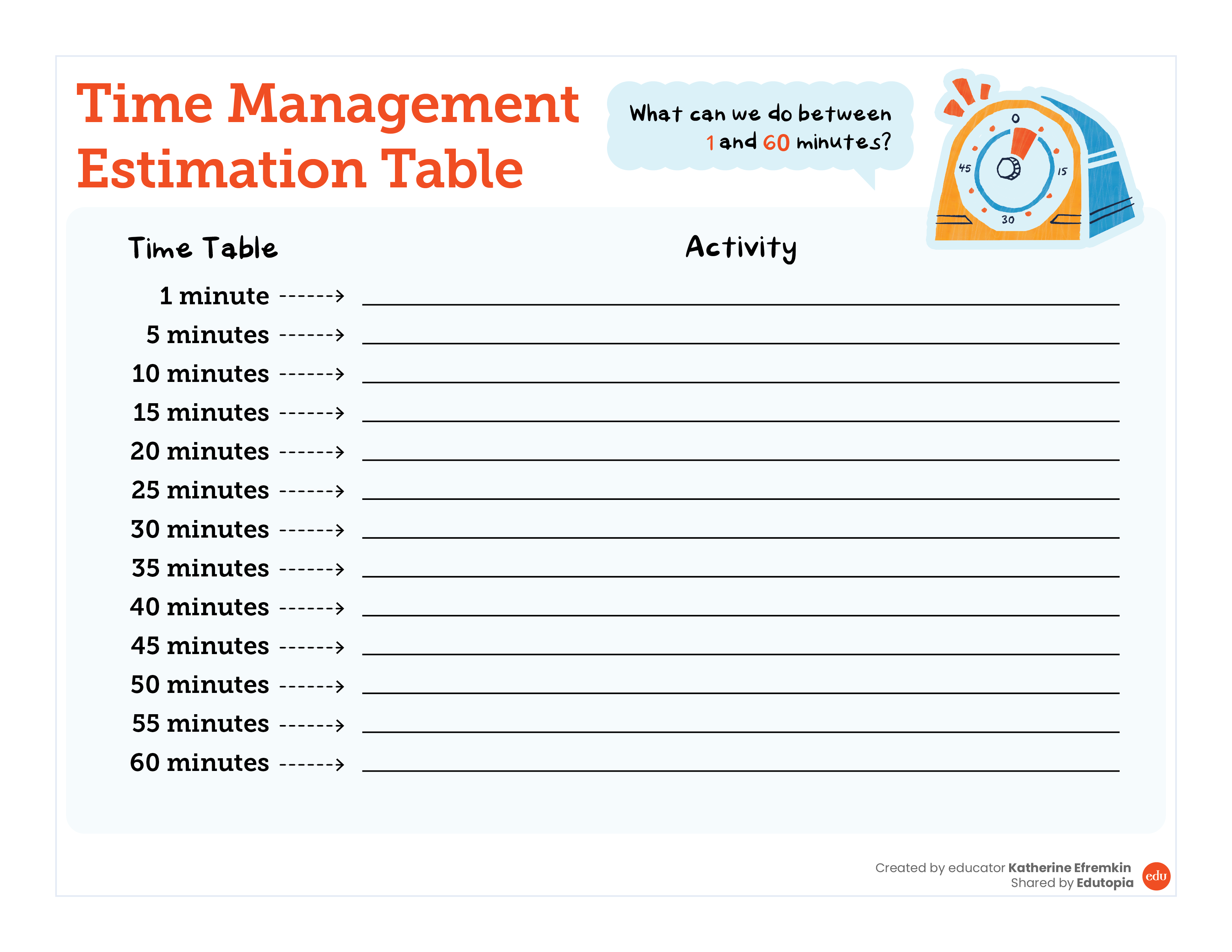

To embed this for consistent practice to lead to generalization of internal time, I introduce a timetable poster. As a class, we think about the activities we do on a daily basis and estimate the time they would take. This helps students conceptualize the concept of time and compare time spent.

I also give examples of when I mis-estimate time. For example, I might say, “Oh no, look at the time, class. In order to make it to specials on time, we will have to wait to write our journal entry until tomorrow. I know so many of you have great ideas, and Mrs. Efremkin made a mistake with her time estimation, because I did not leave enough time for our class to have its great conversation and for you to reflect in your journal. Tomorrow I am going to add five to seven minutes to shared reading to make sure we have enough time for both.” This reinforces the idea that making time estimation mistakes is normal and common.

Embedding Time Management Exercises into Your day

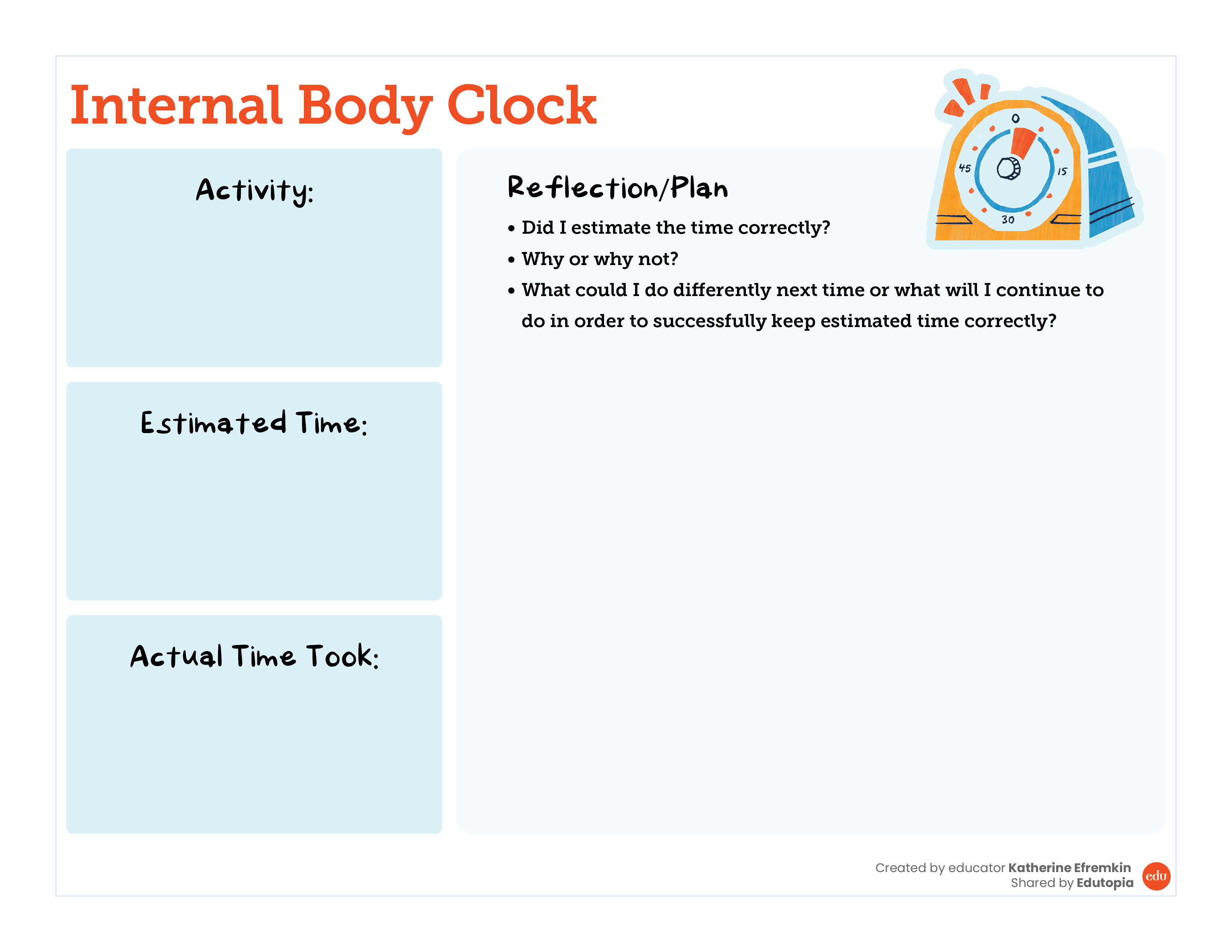

I also embed time management practice throughout the day. I created an internal body clock chart with five columns: activity, estimation, actual time, reflection, and planning for next time. First, as a group we estimate how long a task will take, then we record the actual time it took, and at the end of the lesson we have a one-minute reflection. We analyze why something did or did not go according to plan and create a solution for the next time.

For example, my students estimated that the practice math problem would take the class five minutes, but it took much longer. They reflected that it took longer because it was the first day learning a new skill. This taught them that novel situations often take longer than our initial estimation.

During our morning routine, I ask students to reflect on how long homework took them. This leads to individuals developing their own sense of an internal clock; one student may notice that reading homework was longer for them, as they had to review the text to find the answers, but the math homework was faster because they understood multiplication. This practice helps students distinguish that everyone needs a different amount of time to complete a task.