Teaching Black History, Thought, and Culture Through Art

From Alma Thomas to Jean-Michel Basquiat and Augusta Savage, here are eight remarkable artists to talk about in class—and art projects inspired by their work.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Exploring the vast and brilliant contributions of African American artists is especially significant in February, when educators are looking for creative ways to recognize Black History Month, but it’s also work that can happen anytime during the school year.

As a teacher, I like to use art as a way to celebrate Black artists and start conversations that help situate their experiences in the larger framework of American and world history. It’s a productive way to help students grapple with complex questions and topics and to inspire them to make art that tells their own unique stories.

Here are eight artists—with some details about their lives and creative work—to help get these discussions started in your classroom. I’ve included project suggestions, but you might think of these as starting points: Students could also do their own research to discover other Black artists; learn about their lives, motivation, style, and message; and then make art inspired by what they learn.

Kara Walker

Born 1969

Black and white cut-paper silhouettes were affordable, thrifty portraits before the advent of photography. They’re usually likenesses of people—traced from the subject’s profile cast in light and then snipped out with scissors—resulting in a high-contrast black-paper image against a light background. In the hands of contemporary artist Kara Walker, cut-paper silhouettes become an ethereal story revealing what you might find in the shadows of typically quaint, domestic images.

The power of her work is in the shock of finding strange and sometimes violent imagery where you would expect formality and decorum. She doesn’t shy away from painful imagery and explores the brutality of antebellum slavery and issues of race and gender.

Classroom project: One of the best things about cut-paper silhouettes is the strong impact that comes from inexpensive, accessible materials, making it a deceptively simple medium for investigating complex and even difficult topics. In the classroom, kids can explore cutting out profiles of each other, or use stencils or other objects that strike their interest. For a more involved project, ask students to identify themes that come up in the texts you’re reading together in class—good and evil, honesty and trust, courage and fear—and then brainstorm how to illustrate these themes in a classroom mural, creating a Walker-inspired contrast of complex storytelling and unexpected materials.

Gordon Parks

1912–2006

Gordon Parks created enough work for 10 artists. Born into poverty, segregation, and social upheaval, he was a self-taught filmmaker, writer, and composer but became widely known for his photography. As a photographer for the Farm Security Administration and later for the Office of War Information, he documented social conditions, elevating the work to an art form through beautiful compositions, iconography, and symbolism. Parks saw his camera as a weapon against the unfair conditions afflicting his African American subjects affected by poverty, and he believed that by highlighting and preserving their beauty and dignity, he could invite awareness and forge a connection in the viewer.

Classroom project: Ask your middle or high school students to use their phone cameras to capture a striking image without the benefit of fancy lighting, posing, and multiple retakes or filters. Challenge them to capture action, emotion, or daily lived experience, finding and conveying, as Parks did, the beauty that others might not see.

Faith Ringgold

Born 1930

Faith Ringgold’s award-winning book Tar Beach has lined early-grade bookshelves since it was first published in 1990. The bulk of Ringgold’s work, however, is more confrontational and politically charged. Born in Harlem, she began making art in the early 1960s, unflinchingly documenting and responding to the world through her lens as a Black woman, taking on issues of racism, sexual violence, American identity, family, freedom, and hope. She painted White people at a time when most Black artists did not, flipping the gaze and pushing her art to do the heavy lifting of exploring who is in the center of American history and why. She used quilts, a domestic craft, to tell stories of labor exploitation, systemic economic injustice, and personal agency.

Classroom project: Story quilts are accessible to all ages, but they also can tell complex, unexpected stories, depending on the grade level of your students. For a Ringgold-inspired quilt, use materials like fabric strips or colored paper. You might also explore the rich history of African American quilting, including the quilts of the Underground Railroad that incorporated symbolic language to help Black people escaping slavery navigate their journey.

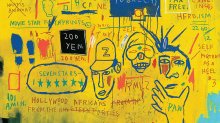

Jean-Michel Basquiat

1960–1988

Jean-Michel Basquiat was extremely prolific, but he died at age 27, leaving a distinctively modern body of work that helps students connect with his world. The very recognizable crown symbol and his tag SAMO—he started out as a high school student spray-painting graffiti on buildings in Lower Manhattan—are recurring motifs throughout his work and became the building blocks of his visual language. Sampling from advertising, educational texts, and historical resources, Basquiat’s work contended with racism, poverty, and access, as well as identity, sexuality, and the addiction that would ultimately take his life in 1988.

Classroom project: Using similar resources—literature, advertising, newspapers, magazines, and other materials students feel inspired by—ask students to tell their own stories in whatever format they’re drawn to. They can even create their own personal stamp or coat of arms.

Alma Thomas

1891–1978

The light, rhythm, and immediacy in Alma Thomas’s work are distinctively her own. She had a remarkably intuitive way of using color to elicit emotion and psychological response, and her large, bright canvases pulse with life.

Thomas, who began painting in the 1960s at age 68, didn’t directly tackle issues of racism and identity the way her counterparts did. Her radicalism lies in the very fact of her existence: She inhabited a space ordinarily occupied exclusively by White men. After just a decade of work, she became the first Black woman to earn a solo show at a major New York City museum—shortly after Black artists staged boycotts of these same museums because they excluded Black artists. Thomas’s work leaves us with questions such as: Where and when can the art of Black women be seen? Are Black artists obligated to address issues of racism in their art?

Classroom project: Students of all ages can emulate Thomas’s kinetic, mosaic-like style by creating paintings or cut-paper collages with intentional color choices that tell stories about the beauty in their lives.

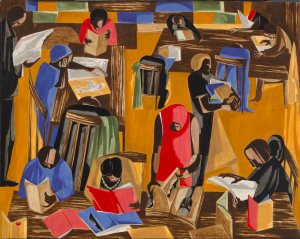

Jacob Lawrence

1917–2000

Jacob Lawrence was a historian and may be one of the most recognizable artists from this list. He documented the African American experience, creating series devoted to Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, and explored migration, life in Harlem, and the civil rights movement. His paintings also depict everyday American life in church, weddings, schools, and shared domestic moments.

His work is characterized by a bold, primary color palette; strong shapes; and simplified, outlined faces that universalize his characters, making it possible for all of us to see ourselves in his recording of history.

Classroom project: In history class, with a canvas of any kind and a way to make color, students can identify key points in a historical narrative and illustrate it as they see fit. Lawrence spoke of the freedom he experienced when painting and the power he felt in being able to make choices about shape, color, story. This idea of power and agency over our own art and story is something to encourage all students to connect with as they create.

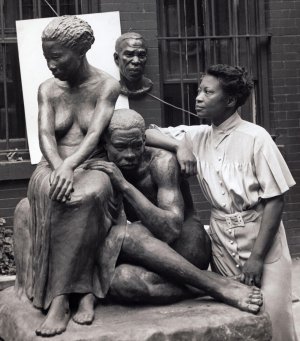

Augusta Savage

1892–1962

Sculptor Augusta Savage was a trailblazing superstar. She moved to Harlem in 1921 to study at Cooper Union art school, and when she was denied a scholarship to study at an art school in Paris, she galvanized support from the press and artistic community until the school relented and allowed her to attend. When she returned to New York, she opened her own gallery, giving others the opportunity she might have been denied. Savage was classically trained and created in classical traditions. Her work was exaggerated and idealized, and sometimes it betrayed the barriers she faced to make her art.

Classroom project: It’s difficult to find another artist who so aptly shows us how to find beauty and possibility in pain and struggle. When Savage didn’t have access to bronze for her sculptures, for example, she used plaster and covered it with shoe polish. Commissioned to create a statue about slavery, she chose to show the power found in faith and exaltation. Classroom discussions about Savage’s work can examine what it means to find equanimity—calm and beauty in adversity—and a related art project can explore this theme using clay or by making 3D art.

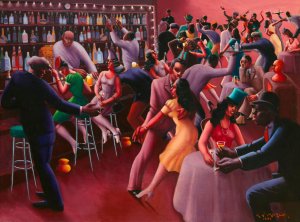

Archibald J. Motley Jr.

1891-1981

The work of painter Archibald Motley, known as a Jazz Age modernist, documented a specific time and place in history and revealed a complex view of the African American experience. Born in New Orleans and trained as an artist in Chicago, Motley was an important contributor to the Harlem Renaissance. Using vibrant color and exaggerated, lively forms, some of his canvases are populated, noisy, and bustling; others are isolated and deeply self-reflective.

He painted the world that he saw and lived: newly elite Blacks on the South Side of Chicago and impoverished migrants who had recently arrived in the city. He wanted to share his world of nuanced and progressive blackness, and he wanted to bring his world of art and culture to his Black community. His belief that art was a great equalizer is still present and relevant in his work today.

Classroom project: Motley’s self-portraits were highly composed and formal, often elegant, aspirational, and embedded with the symbols of his cultural and personal identity. This can be replicated in a classroom with paints, photography, even music or other media. Ask students to consider how they’d like to present their best selves and communicate their ambitions and values.