A PBL Unit on Life as a Young Teen

Project-based learning that’s student-designed and relevant to their lives can have a profound impact.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.The petition landed on my desk during lunch. It was signed by scores of enthusiastic students and even some of my colleagues. Fresh off the heels of Project Carol, which has become a tradition at our school, most students were eager to return to the stage in the spring. This petition would act as our driving force as we began the process of designing an original project.

In recent years, I have owned the challenge of designing a spring project with students. For my entire career, I have tried to weave in opportunities for student voice and choice, but designing a project from the ground up is not for the easily daunted. We have tackled topics such as immigration and homelessness and provided public and interactive community events.

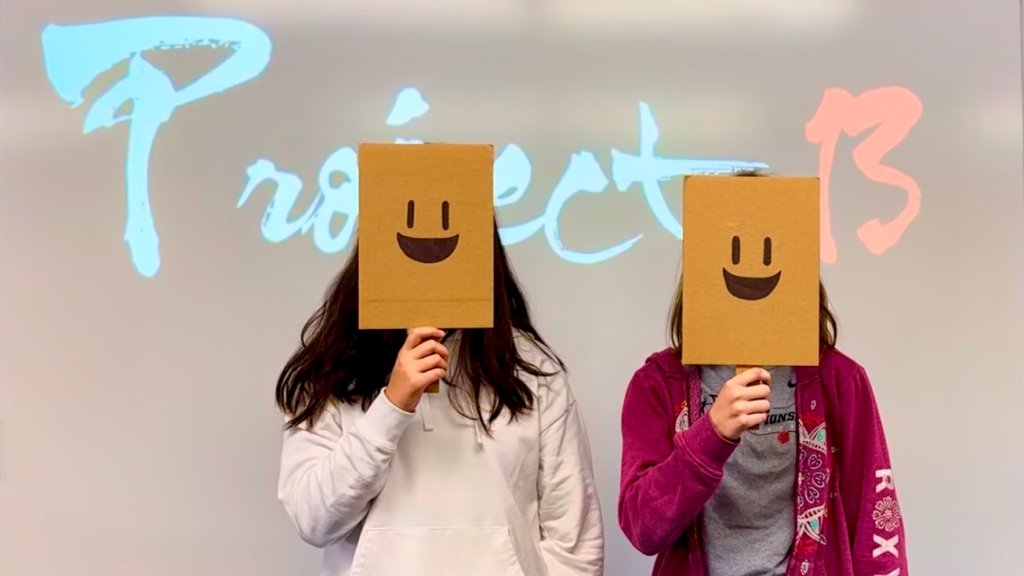

The Birth of Project 13

This year, my students created a broad array of possible topics: warfare, the lasting effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, women’s rights, and the experiences of teenagers. In the end, they settled on the latter, knowing that it was broad enough to include several pathways toward subtopics. We named it Project 13 after the first teenage year and the age of the majority of my students at the time. Everyone would have a role.

Designing a project is similar to playwriting. We started by sharing personal stories: academic anxiety, social pressure, body shaming, sports achievements, and countless others. Students read books and articles in order to broaden their perspective on the teenage experience, and we watched films in class. Some of the most impactful books were A Long Way Gone, by Ishmael Beah, and We Are Not Free, by Traci Chee. In class, we watched Maidentrip, a triumphant story about the teen sailor Laura Dekker, and Grave of the Fireflies, a troubling tale about two siblings trying to survive World War II.

My students cataloged their learning in detailed annotated bibliographies. With broader knowledge, they next focused their learning and interests on a single topic related to the teenage experience. This was their opportunity for a deep dive. The topics for argumentative essays were dynamic, but there was a single topic that consumed more than half of my students: academic anxiety among teens. This gave me critical insight and allowed me to shift from project facilitator and mentor to learner.

Presenting Their Work

Public presentations are always an important part of gold-standard project-based learning (PBL). Students and I decided to engage with the community on two fronts, which we called “acts.” Applying a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, each student would design their own contributions with guidance and assistance from adults and peers.

For Act I, students used their knowledge, interests, and skills to create a classroom maze, which was representative of navigating the teenage years. We called it “The Maze of Emotions.” We purchased PVC pipe and connectors, designed and constructed the maze, and then filled it with writing and art.

This included essays, poetry, confessional letters, paintings on canvas, an unfiltered urban art wall, and other unique elements. These creative pieces acted as windows into the experiences and emotions of my students. For teenage visitors, they were also mirrors.

One student asked visitors to write messages of hope or despair on colored paper during our spring exhibition. He added his own and some from peers and then folded them into 1,000 origami cranes, a process that took countless hours. A group of students created a life-size silhouette of a teenager, attached powerful words and phrases, and then used plastic wrap to “trap” the image inside of the maze. These are examples of UDL in practice.

During our spring exhibition, we had an estimated 500 visitors from our community. This level of engagement and the originality of Act I made it truly special.

Act II was our ultimate destination. Guided by the petition I mentioned earlier, we decided to showcase learning and passions onstage (or in the classroom, for those who didn’t prefer the stage). My students wrote poetry, including multivoice poems, skits, music, and more.

One student performed a 60-second poem while doing a handstand to represent underprivileged teen athletes. Another student wrote and performed an original song called “autotuned,” which was about finding her true voice against all odds. Another invited his mom to the stage, then serenaded her with “Proud of Your Boy,” written by Alan Menken. There was hardly a dry eye in the audience. While Act I was special, Act II was magical.

We overcame many challenges during this eight-week project. We created safe spaces to authentically discuss and present personal issues such as body shaming and academic anxiety. We fundraised for materials such as PVC, canvases, and paint. My students supported each other and turned their shared experiences and raw emotions into enlightening community events.

Project 13 was an insightful and authentic project-based learning experience that was designed and delivered by seventh-grade students. They stood before the final curtain, undaunted. Project 13 was rigorous, lengthy, multifaceted, and something that none of us will forget.