Reflections on Becoming More Culturally Responsive

Participants in a program on culturally responsive teaching practices share what they’ve learned about themselves—and how their teaching has changed as a result.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In a demographic change similar to one that’s playing out across the country, the student body in Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) has shifted from being 94 percent white 50 years ago to just 30 percent today. Nationally, students of color now make up about 51 percent of public K–12 students—a figure the U.S. Census Bureau expects to increase over the next several decades.

This change in student demographics isn’t reflected in the teacher workforce, however, which is 80 percent white. To bridge cultural gaps between teachers and students, many districts are prioritizing professional development around race and culturally responsive teaching, the idea being that in order to meet students where they are, teachers need to know something about where they’ve been.

As part of MCPS’s efforts to help teachers, administrators, and support staff connect with every student, the district worked with McDaniel College and the teachers union to create a graduate-level, 15-credit certificate program called Equity and Excellence in Education (EEE). The classes go beyond providing a toolbox of strategies to help educators develop more culturally responsive teaching practices.

We covered EEE two years ago, and recently we checked in with participants to get their perspective on the program. Educators shared their thoughts about their unconscious biases, their perceptions of systemic inequity, and how they have changed their teaching as a result of the program.

Uncovering Implicit Biases

Participants in EEE spend time examining their own biases, and many have been surprised by what they discovered and by how their students might have been affected.

Thinking deeply about her identity as a white woman for the first time, instructional coach and former fifth-grade teacher Mary Hart reflected on her white savior complex and its negative impact on her students. “There was some hint of ‘I can save these poor kids’ within me,” Hart said. “As a white educator, I have to be careful about that. My kids didn’t need me to save them. They just needed me to respect them, see their greatness, and create an environment where they could feel safe to bring that out.”

One episode in particular caused Hart to really dig into her perceptions of black people, especially black men. A new student joined her class, a black boy with a history of family trauma: “He was angry for many good reasons. Not at me, but at life. The second day he was there, he blew up at another student. In that moment I realized I was scared of him. That threw me because he was rather petite and only 10 years old. My fear was not rational—he was not going to harm me or the other student. He was just a child who needed support.”

Génesis Chávez, a Latina first-grade teacher, asked herself hard questions about her approach to discipline. “Who was I calling out about behavior issues, how was I reacting to them, and how was I handling those issues? Am I choosing to acknowledge misbehavior from my black students more? The school-to-prison pipeline is a very real thing,” said Chávez.

Black educators in EEE were surprised to consider the possibility that they might have contributed to the oppression of their black students, as a result of having internalized negative stereotypes. One of them, Tara-dee Whitely, a high school English teacher, had accepted the idea that black Americans don’t value education. Overcoming her biases, she said, “was a struggle because growing up it was instilled in me that black Americans do not value hard work and only value the quick buck.”

Another black educator, Charles Alexander, a learning and achievement specialist for MCPS and former middle and high school English teacher, had been counseling his black students about what he considered “acceptable behaviors”: “When I taught children of color, I felt the best way to serve them was to teach them how to play the game—essentially code-switch—and adopt white cultural norms,” Alexander said. “The program helped me see how my behavior actually may have harmed a number of students of color, and in particular, boys who looked like me. I thought I was teaching my kids how to make it in the white world, and what I was really doing was limiting them. To them, I may as well have been a white guy in black clothing. I was a part of their oppression.”

Investigating Systemic Inequity

Educators who participated in EEE also talked about what they saw as pervasive deficit-based thinking toward marginalized students. Alissa Casey, a white fourth-grade teacher of English as a second language, said, “The educational system does not always value student and family cultures, experiences, and languages as assets.” Much of public education is structured around getting students to conform “to standards and expectations that are based on the white, dominant culture,” said Casey. “When students and families don’t fit into that mold easily, school systems often see differences as deficits, and create programs to ‘fix’ the students and families instead of re-evaluating the school structures to see differences as strengths.”

“What we are doing as a country is not enough to call our teaching equitable. We are not doing enough to include all of our students,” said Lexi Walsh, a second-grade teacher. There is data to support Walsh on this point: The figures on who gets into and succeeds in AP courses and on different groups’ graduation rates consistently show black, Latinx, and indigenous students lagging behind white students.

After going through the EEE program, many teachers now believe that those inequities extend to the curriculum. “There is still a real lack of truth in the way we teach history. I have been teaching things for years that are not representative of all people,” said Allison Hoefling, a high school history teacher.

“As a white woman, I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” echoed Casey. “I think the biggest surprise was the amount of U.S. history, specifically the history of the systemic oppression of people of color, that never gets taught in schools.”

Taking Action

EEE isn’t just about reflection—toward the end of the program, participants are tasked with creating a capstone project that integrates what they’ve learned into an action plan that addresses a school-wide or classroom issue they have faced.

Hoefling met with her team of history teachers, all of whom are white, to discuss ways to make their curriculum more culturally responsive. Hart is working to publish a research article on the benefits of mindfulness programs as an antiracism tool for schools. And Casey partnered with two other elementary teachers to offer colleagues a three-session professional development course on self-reflection focusing on culture and race.

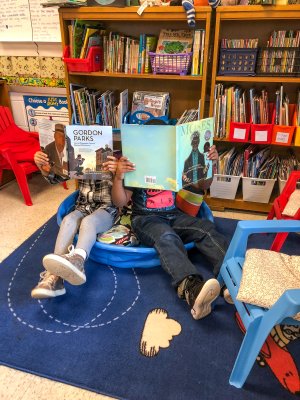

This kind of work doesn’t end when participants finish the course: Chávez says she now ensures that all of her students feel represented in the works her classes read. She makes sure to pick not only works about people of color who are light-skinned or tall—Eurocentric standards of attractiveness—but ones that highlight darker skin tones and indigenous features as well.

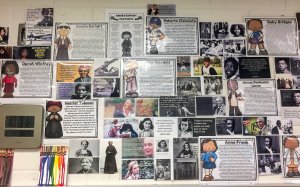

Similarly, Walsh uses her read-alouds to highlight significant people her students can relate to, like Ruby Bridges, Sonia Sotomayor, and Liu Xiaobo. “This has been one of the most powerful things I have ever done in my classroom. Students are constantly talking about how they want to be like the people we have hanging up on our wall and how they hope that one day I will be teaching about them,” said Walsh.

As programs like EEE and districts, schools, and individual teachers develop models of culturally responsive teaching, that’s the goal: Guiding all students to see their potential and a path by which they might reach it.