How Teachers Can Set Realistic Goals

Instead of trying to do everything, focus on what will help you and your students feel a sense of competence in the classroom.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.One of the reasons I was burning out as a teacher was a growing sense of incompetence. I couldn’t figure out why I was always so far behind with work. I felt like my students and I worked diligently, yet every April, I was having to cut whole units that I didn’t have time to teach. (I guess we’re not getting to Rocks and Minerals this year!) Where did all the time go? Was I really so incompetent that I couldn’t get to all I was supposed to teach?

This prompted a thought exercise. For an entire year, I kept track of all of the time that was taken away from my teaching. Every time my students had a fire drill or a bus evacuation drill or I was pulled out of class for an IEP meeting, I logged the time lost on a simple file on my computer. Every time we attended a whole school assembly, missed a half-day for a delayed opening because of snow, or had an extra chorus practice to get ready for a concert, I logged the time lost. Some of these activities (e.g., assemblies and concerts) were good uses of time—educational and important. I wasn’t logging wasted time but time that I didn’t have to teach reading, writing, math, science, and social studies. I didn’t log time spent traveling to lunch or specials (which felt too nitpicky) or time I chose to do something non-curricular (e.g., an extra recess on a beautiful May afternoon). My goal was to see what time I was losing that I couldn’t control.

The results were astounding. Over the course of that school year, I recorded 9,021 minutes of teaching and learning time lost. The number was too big to wrap my head around. Here’s another way to think of it. We had a six-hour school day: students arrived between 8:45 and 9:00, the school day went from 9:00 to 3:00, and then dismissal was from 3:00 to 3:20. Each day we had lunch and recess for 45 minutes, and my students attended a special-area class (music, physical education, art, computer lab, and library) for 45 minutes. So (not counting transitions walking to and from) we should have had about 4.5 hours of teaching and learning time each day. When you convert 9,021 minutes into 4.5-hour days, you get an incredible 33.39 days of school. That’s more than a sixth of the year!

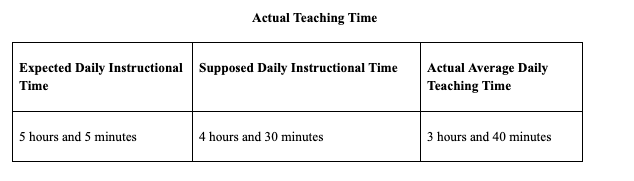

Then I wondered—how much time was I supposed to teach? Expectations were handed out from various people and groups. Our school-based literacy team was encouraging 5th grade teachers to spend 60 minutes a day reading, 45 minutes a day writing, 15 minutes a day engaged in word study, and 15 minutes reading aloud to the class. Our math specialist said we should spend an hour a day on math. Across the school we were trying to carve out 20 minutes each morning for a morning meeting. Forty-five minutes was the understood amount of time to spend on science and social studies each day. When you add these expectations up, you get 5 hours and 5 minutes of time we were expected to teach. But when you factor in the 33.39 days we lost, we actually averaged only about 3 hours and 40 minutes a day. That’s right—we only had about 80 percent of the time we needed. No wonder I felt so incompetent!

What’s even more disheartening (there’s a silver lining coming, I promise) is that you likely have more to teach and less time to teach it than I had during that school year. Local, state, and national testing surely takes more time than it did back then. You know that over the past few decades, more content and initiatives have been added to schools while few have been taken away.

What’s the silver lining? You likely can’t actually get to everything you’re supposed to. It’s not your fault. It’s not that you’re incompetent. No one can teach 5 hours and 5 minutes of content in 3 hours and 40 minutes.

Instead, prioritize. What are some things you can take off your plate? (If you don’t pick something to take off, something really valuable is going to fall off.) For me, this is when I stopped caring so much about homework. It’s not a high-impact practice in elementary school, anyway. I still had to give it—we had a school policy requiring me to do so—but I stopped spending much time on it. This was also when I stopped spending time on cursive writing. We had an archaic school expectation that wasn’t in any standards that 3rd grade teachers taught students how to write in cursive, 4th grade teachers reinforced it, and 5th grade teachers required it in daily work. Then kids went to 6th grade at the middle school where it wasn’t used at all. That was something I could stop spending time on.

What can you prioritize? Can you think of a few things that you and your students spend time on that you can quietly let drop off of your plate? It’s better to do fewer things really well than to do too much poorly.

Set Goals That Support Competence and Connect with Purpose

Of course, one of the ways to feel more competent is to actually become more competent. Good goals can help you get there. So what exactly are good goals?

Good Goals Align with Your Purpose. Too often, the professional goal setting that we go through as part of our annual review process feels forced and inauthentic. It doesn’t have to. Make sure that the goals you take on feel personally relevant and important. What do you care about? What can you get excited about? Even if your school is taking on a new program that you’re not thrilled about, can you find a way to set a goal connected with that program that still feels meaningful?

For example, let’s say your school is adopting a new literacy curriculum that spends, in your view, too much time on shared texts—times when all students are reading the same thing at the same time and in the same way. You care deeply about differentiating learning and supporting authentic engagement with your students. What if you took on a goal of giving small moments of choice for students within the lessons provided? Or what if you found a couple of alternative texts so that students could choose one that is good for them?

At one high school where I worked, a small group of teachers decided to work at offering more academic choices to their students. A couple of them especially wanted to push back on the notion that as content becomes more complex, students seem to get less choice. Their work was innovative, and students’ energy for work increased dramatically, and this group of colleagues was so excited about their work.

Good Goals Are Concrete and Realistic (Perfect Is the Enemy of Good)

“I want to be the best teacher I can be!”

“My goal is to have all of my students exceeding expectations!”

“I will be successful if all of my students are reading at or above grade level by the end of the year.”

Goals like these might feel inspirational in the moment, but they can be problematic for a couple of reasons. First off, they’re likely unattainable. How could you ever be the best teacher you can be? Can’t we always get better? When goals are out of reach, we’ll always fail. Goals that ensure failure aren’t helpful. In fact, they’re going to demotivate you in the long run. Another problem with these goals is that they focus on outcomes that are at least partly out of our control. Imagine that your goal is to have all your students reading above grade level by the end of the year. There are certain factors you can control, such as the quality of instruction, the amount of time students get to read in school, and the availability of high-interest books. You can’t control whether students come to school consistently, whether they read at home, or how much sleep they get each night, which are also factors that can affect reading progress.

Instead, set goals that are concrete, realistic, and focused on what you can control. For example, if you want to help your students become better readers, perhaps you could set a goal of increasing the amount of independent reading time you give to your students each day. Just 10 extra minutes a day would be 1,800 extra minutes in a school year—a significant amount. Want to improve your relationships with students? Set a goal of learning three personal pieces of information about each student in the first month of school. Want to write a blog to connect with educators beyond your school walls? Set a goal of writing one blog post every two weeks. Spend one week drafting and playing with ideas and the second week revising and refining.

When we reach goals that we’ve set, we get a rush of satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment—a strengthening of our efficacy. This helps boost our senses of competence and purpose.

From Rekindle Your Professional Fire: Powerful Habits for Becoming a More Well-Balanced Teacher (pp. 40–45), by M. Anderson, 2024, ASCD. Copyright 2024 by ASCD. Reprinted with permission.