Occupational Therapy Shifts From Tactile to Digital

Since last spring, occupational therapists have been unable to touch and guide students in person—and have had to completely reinvent how they work.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Every day, occupational therapists (OTs) get their hands dirty as they work with students who struggle with fine motor and sensory skills.

OTs guide children’s hands as they learn how to correctly grip a pencil and draw letters, and they help children use various manipulatives, like Play-Doh and blocks, to build strength. They set up Sensory Rooms, where children can bounce on balls and jump on trampolines to release energy so that they can focus on learning. Sometimes, when children are upset, the OTs hold them to calm them down.

But since last spring, when the Covid-19 pandemic arrived in the United States, most occupational therapists have been unable to touch and guide students in person—and have had to completely reinvent how they work. The adaptations have been especially challenging because many children with special needs depend heavily on parent/caregiver oversight to help them with tech tools or even to sit still to focus during remote education.

“I’m incredibly proud of myself and my team here, because we weren’t even sure how to get kiddos to the screen at first. I really didn’t know much about technology when we went to remote learning in March. We’ve come so far,” said Monica Keyser, an occupational therapist in San Ramon Valley Unified School District in California.

OTs like Keyser say they’ve found new apps and tech tools or modified their traditional methods for use in virtual and in-person sessions. All said that they are most successful when a parent is available during the day to assist their child, but that equity issues tied to families’ resources can create barriers to that engagement. While exhausting, these experiences have helped therapists evolve their work, which will benefit kids long after the vaccine arrives.

“My learning curve this year has been a mountain. It has been huge,” said Linda Kinkade, an occupational therapist for the Warrick County Schools in Indiana. “I figured out that I’m not too old to still learn, which is kind of a weird blessing in disguise.”

Tech Transitions

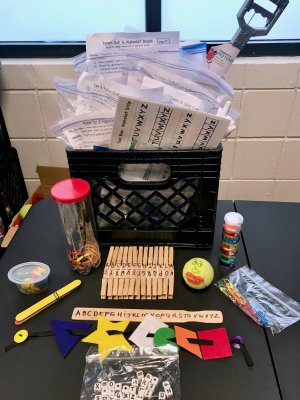

While assistive technology tools like voice recognition software have become increasingly common in special education, these tools have traditionally only been part of an OT’s toolbox, which relies heavily on more commonplace objects, like crayons and Play-Doh. Now, with the additional onus of reaching kids at home, OTs have had to turn to a new array of tools like Google Jamboard, XP-PEN, and Boom Cards to keep students learning.

“I will say that as occupational therapists, our training is in adapting to situations to help our students meet their needs,” said Keyser. “We’re always looking for ways to help our kids. Providing virtual services is not anything I learned in school, but we’re figuring it out.”

Keyser, who has been working with her intensive-needs students virtually since last spring, uses video to show students and caregivers how to do activities she once demonstrated in person. On Zoom calls, participants watch her as she forms letters on her whiteboard in her office, and then they mimic her efforts at home, sharing their screens as they draw letters on the iPad so that Keyser can track their progress.

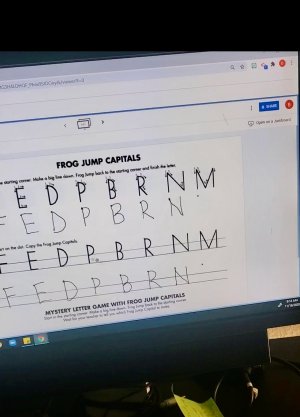

Other therapists have used Google Hangouts or Zoom to supervise students using traditional worksheets and curriculum, like Handwriting Without Tears, Fine Motor Boot Camp, and Tools to Grow, and some have been trying out completely new tech tools.

Krista Stephens, an occupational therapist from Florence, South Carolina, said she’s been using Nearpod to create interactive slides that pique students’ interest while helping them develop important skills. She includes live, interactive mazes that students can draw on using their mouse, for example, or pictures, forms, or letters that students copy on paper. In some cases, the tool itself has become the therapist when she’s not there to guide them: Her kids are learning how to type using TypingClub, and the “Crocodile Snap” song, a YouTube video, teaches children different hand motions like snapping and wiggling that help them learn how to grasp a pencil. She also uses computer-based Boom Cards activities to target skill areas such as matching similar pictures and distinguishing colors, shapes, and letters.

Technology has served another purpose too, Stephens said: Sometimes, online games are the only way to get her students with more severe needs to participate at all in virtual education. Stephens found that playing games on Boom Cards helped two of her students—brothers with autism—engage with her through the computer, as well as focus a bit longer. “Little did they know they were doing therapy while they were playing,” she said.

Working With Parents

Given that many students receiving occupational therapy are very young and may have attention and cognitive deficits or behavioral issues, guiding students through their exercises in remote or hybrid learning often requires the active involvement of a caregiver.

“It’s been a learning curve,” said Kinkade, who said she realized quickly that she had to work in tandem with parents on everything from sharing the work of the student to finding or repurposing items to use during their therapy sessions.

Like many educators, Kinkade made homework packets for students in the spring before schools went remote. These assignments also offered recommendations for parents on how to use commonly found household items like Legos, pennies, and Cheerios for exercises that help their children build strength, fine motor coordination, and the pincer grip.

In lower-income communities, however, reliable technology and the assistance of a parent or caregiver are not always available, according to Brittney Harvey, an occupational therapy assistant who works with students in several public schools in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Harvey said these two factors make a considerable impact on how successful students can be in the remote setting, which has exacerbated equity gaps between students.

Though these challenges are not easily solved, Stephens recommends communicating with parents weekly with newsletters, email, or even videos with information about the therapy schedule, materials that parents should assemble ahead of time, and goals and themes for the week. In addition, she sends a friendly email reminder the day before a therapy session because she knows that parents are often juggling multiple children and their own work schedule.

Keyser suggests asking her parents to practice the exercises from their therapy session and to give her feedback by email on these activities. “I will most often start our sessions with questions, like “How did it go with the Play-Doh cutting activity? What did you find challenging? Were you able to note any progress on your child’s use of scissors?” These questions and this feedback help parents become more invested in the therapy, she said.

Evolving the Work

Learning how to innovate and adapt, while challenging, could improve how occupational therapists reach and support their students in the future, therapists say. “Having to be innovative and think on your feet is one silver lining from this whole thing,” Harvey said. “It has been a rewarding but challenging year.”

The increased reliance on new tools, for example, has pushed schools to become much more tech savvy—and better resourced—which may improve the options that OTs have for both in-class group interventions and remote teaching emergencies in the future.

“Our district is now pretty much a one-to-one Chromebook district, and we were not before Covid,” said Jan Hollenbeck, an occupational therapist and special education coordinator in Medford, Massachusetts.

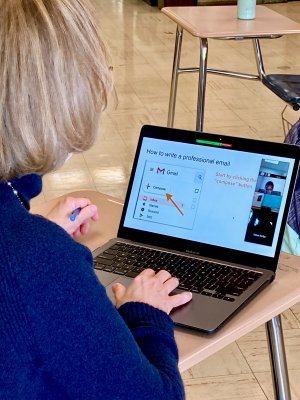

To help students take advantage of these new tools, the occupational therapists and other special education staff in her district created a curriculum to train high school students with special needs on a range of technology skills, she said. Students are learning how to check email regularly and respond appropriately; how to access a Zoom call and maintain a schedule; and how to take a screenshot, attach a document, and electronically submit assignments—skills that will benefit them long after they leave K–12.

While virtual education has, overall, been less effective than traditional in-person education, therapists say that stronger relationships have been forged with many families due to increased communication and collaboration.

Kinkade emphasized that virtual sessions gave her a new perspective into her students’ worlds. “Many times there were other children in the home and parents working from home that at times almost turned into a counseling/support session helping the parent to balance their new world,” she said.

She and Hollenbeck noted that these new connections have led to OTs coaching children on tasks they typically learn at home, like fastening buttons on a shirt and preparing meals, along with helping parents develop habits and routines to support home learning—all of which help reduce stress for overwhelmed families.

And the new connections between therapists and parents also mean that families now have a better understanding of what happens at school. “By talking with the parents, the parents now understand what I do,” said Harvey, who says that in the past, parents only talked to her at IEP meetings. “There is a new appreciation for the profession.”