Lessons From the Cigarette Wars: Harness Student Voices Against Vaping

The number of kids who are vaping has risen dramatically in the last year—and the addictive habit has now claimed its first lives. It’s time to let kids know we’ve seen this all before.

Your content has been saved!

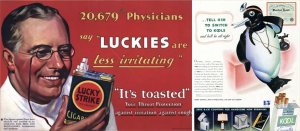

Go to My Saved Content.By the time the lecherous cartoon dromedary named Joe Camel appeared on U.S. billboards in 1988—he enjoyed a nine-year run as the poster boy for what we’d now recognize as toxic masculinity—the product for which he shilled had traced a long and improbable arc through the American imagination. The modern cigarette, from the outset a device for delivering addictive doses of nicotine amid a cloud of carcinogenic byproducts, was—during its heyday from the 1920s to 1960s—an iconic symbol of rebellion and prestige, at once socially transgressive and fashionable. The product seemed to move effortlessly between the poles of its wildly contradictory reputation, finding its way into the hands of public figures as various as lithe supermodels, disaffected rock stars, sharply dressed businessmen, and celebrity rebels like James Dean.

The first mass-produced cigarettes were marvels of industrial design, too: sleek, pristine tubes of tobacco that felt precision-tooled, sophisticated, aseptic—perhaps even hygienic. At any rate they were perceived as better, and healthier, than the filthy cigars and adulterated snuff that had been their predecessors, and tobacco sellers marketed cigarettes as a form of progress. New menthol flavors made them go down easier, proclaimed the Kool brand, and filter-tips—which debuted in the 1950s—promised to render them harmless (but in fact made them worse). In 1942, the famous designer Raymond Loewy—creator of era-defining packaging and products like the Coca-Cola bottle and a line of Studebaker automobiles—added to the cigarette’s mystique, improving on an existing design and encasing them in an iconic, lightweight pack for the Lucky Strike brand.

For decades, the advertisers and designers outran the science: doctors were bought off or were simply uninformed enough to testify for the benefits of cigarettes, and in the uncertainty that reigned—it must have felt a lot like the present moment in the vaping crisis—the product remained largely immune to criticism. It wasn’t until the 1960s, some 40 years after the modern cigarette rose to prominence, that cigarette packages began to bear the disfiguring scars of an emerging battle over the future of the product. Under pressure from institutions like the American Cancer Society, and in the wake of the first studies linking smoking to cancer, mandatory health warnings in large blocky letters—and later pictures of horribly diseased lungs—were stamped like stigmata on every box.

But it was far too late.

Hooking Kids, All Over Again

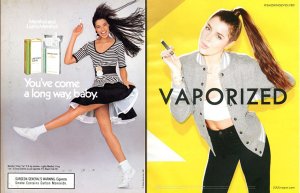

The product had appealed first to men, then jumped to women in spectacular surges in the 1920s and 1960s, piggybacking cynically on the promise of new freedoms for women. More tragically, and in no small measure due to characters like Joe Camel, the cigarette—a veritable death sentence, we had come to learn—appealed to the young.

The long-running Michigan study that recently made headlines by announcing that 27 percent of high school seniors had vaped in the last 30 days—and almost one in 10 eighth graders—recorded similar percentages of young cigarette smokers in 1976. A 1984 document from the R.J. Reynolds Corporation, unearthed years later, revealed that the company viewed young adults as their “only source of replacement smokers.” And the Joe Camel ads starting in 1988 did the trick, improving the company’s market share among 12-18 year old smokers from 3 percent to 13 percent.

Only a few years later, in 1991, a researcher following a hunch revealed that the Camel company had lured another audience in the process: Among pre-schoolers age 3-6, Joe Camel was beloved, tying with Mickey Mouse as the most recognizable branded image among 22 competitors. A full 91 percent of 6-year-olds could match Joe Camel to the product he represented.

The carnage that followed in the wake of those campaigns was staggering. In 1963, during a single year at the peak of the tobacco crisis, Americans smoked 523 billion cigarettes, about 2,800 for every person living in the country. Smoking 10 cigarettes a day “doubles the risk of death,” according to research reported by the Washington Post, and an astonishing two thirds of smokers “will die early from cigarette-triggered illness.” In the 20th century, the cigarette and other tobacco-related products claimed the lives of more than 100 million people worldwide, and the World Health Organization says tobacco-related illnesses are on pace to kill one billion people in this century.

History is an imperfect guide to the future. The destinies of cigarette smoking and vaping may not move along identical paths—or start and end at the same place—but the general shape of the problem looks familiar. It’s true that studies have shown that vaping, thus far, appears to be safer than smoking cigarettes, and that vaping might help adult smokers kick the cigarette habit, though the science on the latter claim is murky.

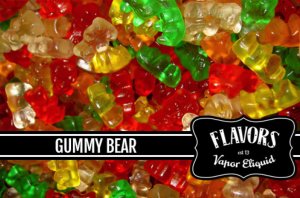

But it took decades to understand the true impact of cigarettes, and there’s simply no mistaking the intention behind the optimistically named JUUL Starter Kit—the company is the leader in the vaping industry, registering $1.3 billion in sales in a recent one-year period—or the newer, more customizable vaping devices with their digital touch screens, data-rich readouts, and personalized settings. Like the cigarette before it, the line of vaping pens, MODs, and e-hookahs are often beautiful, modern tools designed to feel like expressions of the age—touchstones for kids who want to signal that they’ve arrived.

Meanwhile, the numbers behind vaping continue to tick up ominously. The percentage of teenagers and middle schoolers who vape has nudged up close to some of the high-water marks the cigarette achieved in the same age group. A sudden whirlwind of deadly, vaping-related respiratory illnesses recently swept across dozens of U.S. states, sickening more than 500 and killing eight.

And research is quietly confirming some of the more worrisome speculation about vaping: a 2016 Surgeon General’s report joins a growing body of evidence in concluding that adolescent exposure to nicotine—the addictive chemical is present in high concentrations in the vapor kids are inhaling—“may have lasting adverse consequences for brain development.” Other studies are beginning to suggest that harmful metals and lung-damaging chemicals like diacetyl may be inhaled along with the flavored vapor the industry claims is squeaky clean.

Teaching Tactics That Work (and One That Doesn't)

1. Avoid lectures about the risks: The urge to deliver dire warnings about the risks of nicotine addiction and long-term damage to the brains and lungs of kids is understandable, but studies show that middle school and high school students simply don’t listen. The research is unequivocal on that point. In his 2014 book, Age of Opportunity: Lessons From the New Science of Adolescence, the researcher and renowned expert on adolescent development Larry Steinberg summarizes: “most systematic research on health education indicates that even the best programs are successful at changing adolescents’ knowledge but not in altering their behavior.”

Teaching middle and high schoolers about the health risks associated with vaping is crucial of course, but it’s not enough to deter them.

2. Show them the money: Adolescents do respond powerfully to the idea that they are being taken advantage of, or are playing an unwitting role in a societal injustice. According to Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, a professor of cognitive neuroscience and author of Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain, one major study from 2000 tested the effectiveness of a range of anti-smoking messages on adolescents. The most effective campaigns focused on the problem of second-hand smoke (putting younger children in danger, in particular) and on the idea that an adult industry was engaging in the “deceptive portrayal of a lethal product” to make money and hook kids. “If you focus on things like that, you can change attitudes,” she concluded.

For teachers that might mean designing a media literacy lesson by collecting relevant research, articles, and advertisements and then allowing students to draw their own conclusions about the motivations—and the honesty—of the tobacco and vaping industries. A Google image search of “vaping and tobacco advertisements” is a simple place to start. Other good resources: Stanford’s brilliant, encyclopedic overview of tobacco and vaping ads (use the top nav) and their excellent 2019 study of JUUL’s marketing tactics, along with Vox’s thoughtful coverage of Stanford’s work.

3. Elevate student peers (and reduce your own profile): At Arrowhead High School in Milwaukee, principal Gregg Wieczorek sends some of his students to feeder schools in the area to talk with younger students about vaping. “I’m hoping that when the middle schoolers see this kid they looked up to on the basketball team saying, ‘Vaping is bad for you and here’s why you shouldn’t do this,’ it might have more impact on them than the teachers or parents saying it,” Wieczorek said.

He’s right. According to Blakemore, “If you want to promote healthy choices or anti-smoking to young people then you don’t focus on the long-term health risks. What they really care about is what their friends think.” Blakemore went on to say that the lesson applies more generally: Anti-bullying campaigns in middle school led by popular kids, for example, “have a much better effect on attitudes towards bullying and actual instances of bullying than the same campaigns led by teachers—and the same is true for smoking.”