How to Build Better, More Effective Tests and Quizzes

Your tests might be falling short due to a few fixable missteps. Here’s how educators are fine-tuning their approach for better, more accurate results.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.A well-designed test can offer valuable insights into what students know, clarify where misconceptions linger, and drive future learning. But they can also leave a lot on the table.

When test questions are poorly constructed, for example, students may rely on rote memorization or guesswork rather than tapping into deeper understanding, and when testing stakes feel too high, students may struggle with test-related stress and anxiety, which clouds the picture of what they really know.

Some nips and tucks to assessment practices—like increasing the frequency of tests, lowering the stakes, pretesting prior to instruction, and occasionally letting students write tests themselves—can lead to noticeable gains in students’ confidence and make instruction more responsive. But examining assessment strategies isn’t just about making tests more engaging or less stressful for students; it’s about making them more effective tools for learning.

When well-conceived and richly varied in format and timing, tests and quizzes have the power to dramatically improve “long-term retention and the creation of more robust retrieval routes for future access,” the authors of a 2023 study write. When students took brief retrieval tests prior to a high-stakes test, for instance, they remembered 60 percent of the material—an impressive 20 percent more than their peers who had not. The occasional alternative assessment, meanwhile, can open unexpected windows of opportunity for students, challenging them to apply their learning in novel ways while showcasing unique strengths that traditional tests and assignments might overlook.

We scoured the research and our Edutopia archives, as well as popular edchat forums, to find nine ways to sharpen and expand your assessment practice.

Reimagining Quiz Design

Traditional quizzes often prioritize quantity over depth—multiple chances to show mastery and the opportunity to score enough points to pass without really grasping the material, writes middle school math teacher Nancy Ironside. Additionally, certain types of questions, like multiple choice or fill-in-the blank, can tell you what students remember, but not whether they truly understand key concepts and how to apply them in a variety of contexts. Effective assessments require students to engage more critically and thoughtfully with the material—encouraging them to explain, reflect, and even sometimes create.

Consider a Less Is More Approach: Rather than offering 10 multiple choice questions, consider narrowing a quiz down to five, suggests educational consultant Jason Kennedy, and then try a twist: Instead of having them choose the right answer, ask students to pick two bad answers for each question and explain why they’re incorrect. While anyone can guess what’s right, he says, “it takes understanding to explain a wrong one.”

Alternatively, Ironside says, a quiz with only one question offers students an opportunity to show what they know without “awarding points for the sake of points.” She starts by building a diverse bank of standards-aligned math problems, regularly revising them to keep them relevant and interesting. Next, she sorts the problems into three to five difficulty levels based on students’ different proficiency levels. When administering the quiz, each student is assigned a problem appropriate to their level.

Break the Pattern: On assessments, educator Rachel Williams Miller likes to add a closing question: What have you learned during this unit that you did not have an opportunity to express on this assessment? This throws the ball back into the students’ court, offering an additional pathway to demonstrate their learning that may feel less daunting and challenging them to momentarily reflect. “You would be surprised how much the kiddos can recall when not confined to patterns of assessment,” adds educator Jeanne Morris.

Let Students Write the Test: When students are involved in the test- or quiz-creation process—by generating some of the questions, for example—the additional cognitive effort pushes them to think more deeply about the material and consider it from new angles, strengthening their understanding and memories of what they’ve learned, according to a 2014 study. Students who generated a “significant” portion of their evaluation exams—and developed learning materials for the class—experienced a whopping 10 percentage point increase in their final grade, the researchers note. Consider tech tools like Kahoot and Wayground, which make creating quizzes collaborative and easy for students.

Lower the Stakes

Mostly, some degree of stress can be productive—encouraging students to study more, for example, or complete an assignment on time. But high stress levels “disrupt the brain’s learning circuits and diminish memory construction, storage, and retrieval,” writes neurologist Judy Willis. The impact can be substantial, she says: “Neuroimaging research shows us that, when stresses are high, brains do not work optimally, resulting in decreased understanding and memory.” A few low-lift adjustments can lower the testing temperature, making it a more accurate reflection of student understanding.

Get Them Talking: Early on, some students begin to associate tests with performance, explains Howie Hua, a math lecturer at California’s Fresno State University: “Students think, ‘Not only do I need to get it right, I need to get it right fast.’” To slow down and alleviate some pressure, Hua and his co-teacher, the late Diana Herrington, came up with Test Talks. After students put their writing utensils on the floor, Hua hands out tests and allows the class to talk to each other about it for five minutes before taking the tests individually.

Test talks aren’t a space to try to learn something new, one of Hua’s former students said, but they do “give me an opportunity to double-check my uncertainties with my classmates, which gives me more confidence and settles my nerves before taking a test.” Not only do students experience less anxiety, Hua says, but as a teacher you’ll feel “better energy in the room,” as well as improved outcomes and discussions.

Practice, and Then Practice More: It might sound counterintuitive, but a great way to help students feel more confident with tests is… by giving more tests! When they’re practicing enough (and receiving feedback directly after testing), you can “take away some of their anxiety,” explains retired veteran teacher Jay Schauer. Students will know how well they’re going to perform and be reminded that “they can do this kind of problem."

A 2014 study illustrates how frequent, low-stakes practice tests can deliver a powerful memory boost and surface key misconceptions early in the learning process. For the best results, mix testing formats up—multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank, short answer; make time to give tests right after the lesson and keep up the habit as the year progresses; and to ensure that students know why they got a question right or wrong, offer timely feedback.

Respect Student Privacy: Teens are navigating a social media landscape where “nearly every moment of their lives can be shared and compared,” writes author and researcher Devorah Heitner. Grade-sharing can create stressful competition between peers and draw negative attention that some might prefer to avoid. To keep that culture of comparison to a minimum in her classroom, teacher Rebecca Olivares moves grades to the last page of the assessment so that students can keep grades to themselves. Many “like the privacy it provides,” she says.

A More Flexible Approach to Assessment

Creating multiple opportunities for students to show what they know paints a more complete picture of student learning, writes Andrew Miller, a director of curriculum and instruction. It’s important, he says, to be “more flexible and to approach assessment of student learning as a photo album or a body of evidence,” rather than a single snapshot.

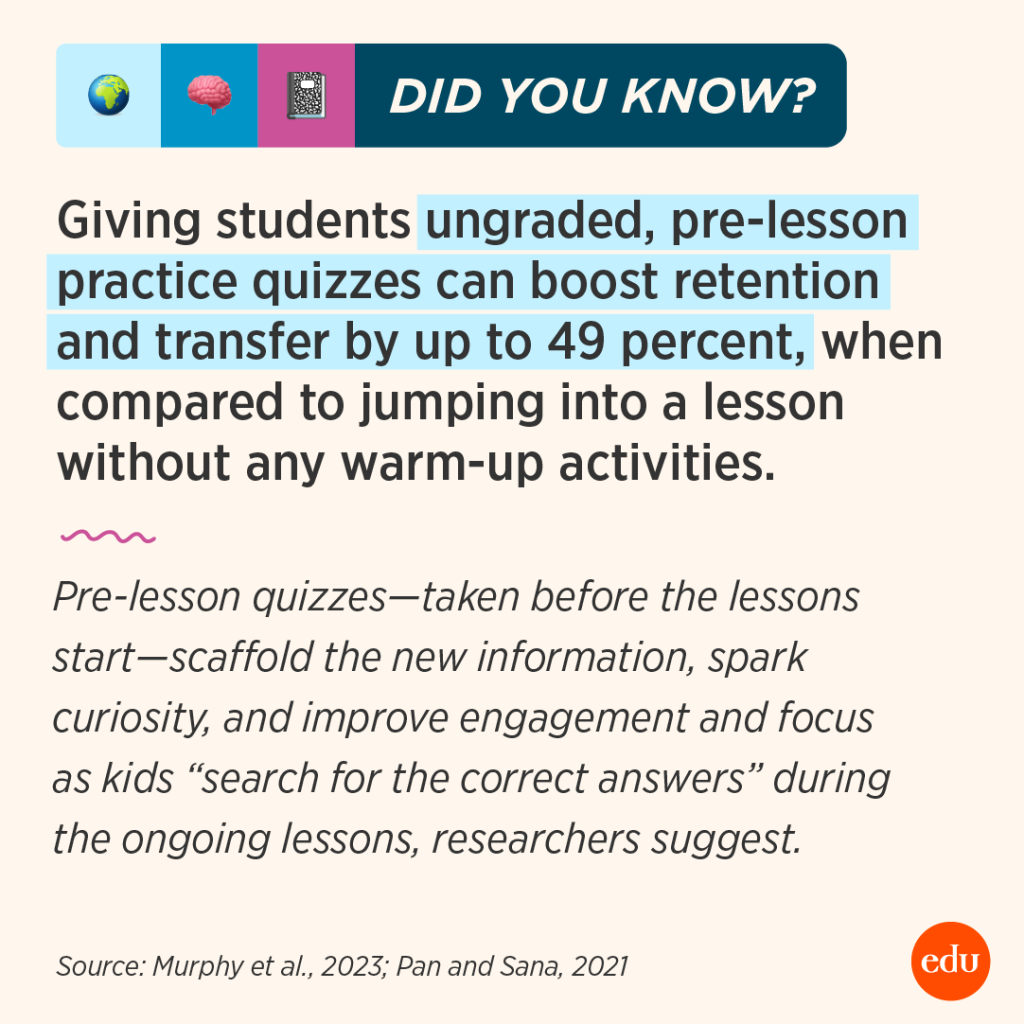

Don’t Overlook Pretesting: Testing before students have encountered the material might feel pointless (especially if many are simply guessing the answers), but a 2023 study suggests that pretesting prior to instruction can actually improve long-term performance “even if [students] are not able to answer any of those questions correctly.” The process of generating errors sparks curiosity in students and sets them on a search through the next few lessons to find the correct answers. Educational consultant Colin Seale suggests following up with students’ “good mistakes,” asking questions like “What makes you say that?” instead of outright dismissing wrong answers when reviewing.

Mix It Up: Traditional tests are just one tool, of course, for assessing students’ content knowledge. Alternative assessments, strategically used at key points in a unit, can inject a more nuanced picture of learning—they can also be fun.

- Group quizzes, for example, “incorporate recall, revision, repetition, and reinforcement,” Schauer explains, and studies from 2009 and 2014 confirm that when students take tests in groups initially, they perform better when the time comes for solo tests.

- For students whose skills and interests fall outside the traditional academic mold, it’s occasionally important to offer more creative options. High school science teacher John Dorroh allows students to create posters or detailed sketches with an accompanying fact sheet that connects the artwork to 10 key concepts they’ve learned.

- For a more playful take on oral assessment, middle school teacher Jessica Guidry has her students role-play as scientists “persuading the members of the UN to keep their chosen biome alive.”

- There are also video essays or recorded debates, which allow students to demonstrate knowledge using tools they gravitate toward in their spare time.

Occasionally, Make It a Conversation: A single assessment can reveal a lot, but it often doesn’t tell the entire story, instructional coach Tyler Rablin says. That’s why he asks students to help fill in the gaps. Every two weeks, he sits down with students individually to discuss their assessment results. “I’d say, ‘This is what I’m seeing,’ and the student could now say, ‘Here’s something else that shows that I really know this. Yes, I struggled here, but look at this other piece of writing where I did well.’”

For students who struggle to show what they know on traditional tests or quizzes, consider offering quick follow-up interview assessments—an additional opportunity to recall information and “share it in a kind of relaxed way,” explains educator Theresa Williams, who likes to carve out five minutes or less for a one-on-one assessment conversation with her students.