Schools Try AI as Student Mental Health Needs Surge

Social-emotional, behavioral, and mental health needs are outpacing what schools can provide. Can technology—namely AI—step in to help?

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Jasmine*, aged 9, had just lost her home in a fire. She didn’t need 30 pairs of eyes staring as she walked back into the classroom. But coverage on the evening news had already spread the story throughout the community, and now her fourth-grade classmates, anticipating her return to school, were brimming with questions: What started the fire? Where is she going to live? Does she have a TV? Did the fire burn her? Is she OK?

Confronted with an emergency, teachers struggled to balance competing priorities. As a group, they needed to acknowledge the tragedy while shielding a vulnerable little girl from a swirl of unwanted attention. Her classmates, too, needed help processing new information: Loss and grief are complex concepts to understand at 9 and 10 years old. Meanwhile, classes in math, science, and English language arts had to continue. The school would have to hold space for all of it.

Creating customized support materials might require Alicia Wilson to carve out several hours she didn’t really have—time away from the 22 other schools under her care, each with its own ongoing crises and student needs. As the New York regional director of social work for the Uncommon Schools charter district, she wanted to ensure appropriate support for the affected student, prepare Jasmine’s teacher to handle the classroom conversation sensitively, and help an entire peer group process their emotions.

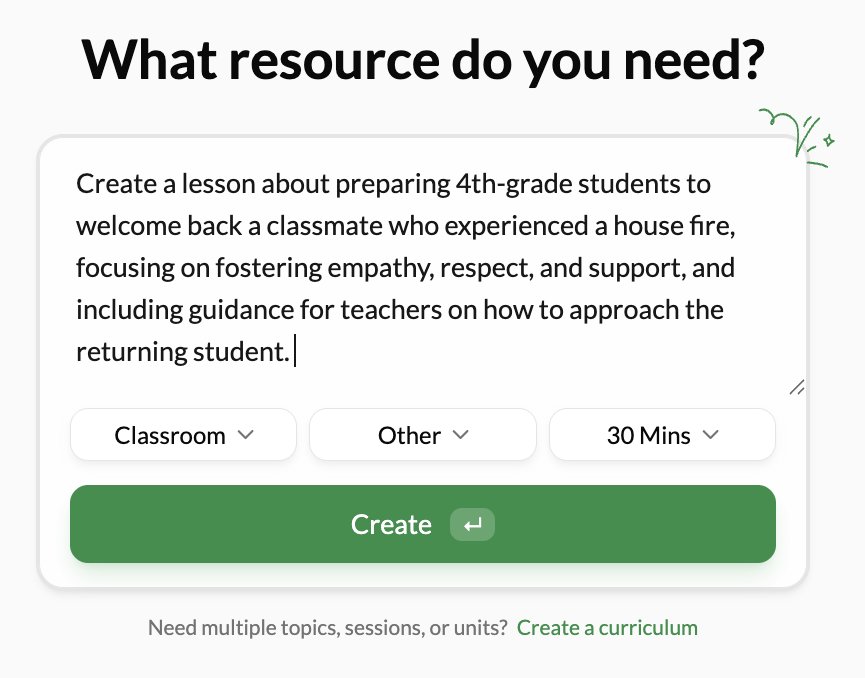

In her hour of need, faced with a complex human problem, Wilson flipped open her laptop and turned to Lenny, a friendly, AI-powered avatar that sifts through a library of clinical research and pedagogical best practices before generating age-appropriate lesson plans and interventions. In a few minutes, Wilson had a draft lesson plan she felt she could work with.

CALMING LITTLE MINDS

That a teacher, counselor, or administrator—like Wilson—would suddenly find themself supporting emotionally distraught children with the assistance of artificial intelligence may feel like the premise of a futuristic novel, but it’s actually the symptom of a longstanding problem with roots in the analog world.

Reflecting broader, decades-long shifts in the nation’s social safety net, schools are now the “de facto mental health system for many children and adolescents,” according to a 2020 study published in JAMA Pediatrics, with nearly one in five students accessing school-based mental health services in the 2024–25 school year, recent data shows. Over the last decade, meanwhile, the mental health needs of primary and secondary students have been rising in both volume and complexity, squeezing an already overwhelmed school system and placing teachers in positions they lack both the time and expertise to navigate.

School counselors are trained to handle many of the issues, but the role remains chronically underfunded nationally. While the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) has long recommended K–12 staffing ratios of one counselor for every 250 students, the 2023–24 national average was 376 students per counselor, and several states scraped by with ratios of over 500 and even 600 students per counselor. In 2019, according to an ACLU report, more than 14 million K–12 students, most of them living in low-income or rural areas, attended schools that had no counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker. Emergency funding that schools received during the pandemic has long since run out, and despite the U.S. Department of Education's reinstatement of some previously discontinued grants, demand severely outpaces supply.

The surge in student needs has been felt in the Uncommon Schools network, Wilson confirms. Scaling support services to meet diverse and growing student needs is a “significant challenge we’ve faced,” she says. In their current setup, with just one social worker serving over 350 students, “the demands are immense—juggling attendance barriers, housing and food insecurity, classroom mental health issues like anxiety, and navigating access to health care without insurance.”

So when tragedy struck a student in their community, Wilson thought the technology could be a real asset. She asked Lenny to “help our staff develop a plan to inform students about what happened and how they can support their classmate when she returns, without bombarding her with intrusive questions.” After Wilson provided Lenny with necessary context—the number of students, time constraints, learning objectives, and student accommodations or special needs—she and the chatbot cocreated a lesson titled “Helping Hands, Kind Hearts” (click the download button to see the lesson Lenny generated).

Leveraging insights from reputable organizations like CASEL, ASCA, and the National Center for School Mental Health, the AI-assisted lesson offered guidance that the chatbot itself said used “trauma-informed practices” and aspects of “constructivist learning theory” emphasizing the importance of students actively “constructing their own understanding” rather than “passively receiving information.” The lesson plan included recommendations to support the returning student, a framework for conducting a class discussion on what it means to be a good friend during tough times, and a small group activity where students brainstormed respectful things they could do and say (as well as what to avoid).

“Teachers felt Lenny provided them the tools to calm their little minds and be mindful of how they showed their love for their classmate,” Wilson said. Jasmine’s mother appreciated how much intention and care was put into ensuring that her daughter’s return was as normal as possible.

During lunch, a little boy asked Jasmine if she wanted to talk about the fire, to which she said no. “The student said, ‘OK, what would you like to talk about?’ [Jasmine] said, ‘I just want to play a game,’ so he got several students and they played a game,” Wilson recalls. As Jasmine left school that day, her bag was filled with cards from her classmates.

‘OUT OF STEAM’

Even in schools fortunate enough to have well-staffed mental health services, the work of supporting students remains complex, Lenny Learning’s founders Ting Gao and Bryce Bjork explain. Mental health professionals in K–12 schools are attempting to “connect the dots between thousands of research papers released every year—hundreds and thousands of hours of content that’s publicly available—and determining which ones to use,” Gao says. Then there’s finding the right fit for the students, whether it’s a whole classroom, a small group, or a single child. The power of AI, the pair say, lies in streamlining that process: “That’s what Lenny does: He connects the educators and counselors on the ground to all of these resources and helps them pull it all together in one fell swoop so they can focus on the students.”

Lenny is currently being used in over 400 schools with over 210,000 students across 19 states, representing a 10x growth rate from the 18,000 students they were serving at the beginning of 2024. Teachers can explore the platform for free, but school-wide usage costs $4,975, with custom pricing offered for full districts. While some schools utilize Lenny across grade levels as well as in and outside of classrooms, North Carolina–based mental health support therapist Brittney Bullard tends to access the platform mainly when she’s in a pinch. “I don’t read from a script; I know how to integrate this into my practice,” she explains. “I might use parts or pieces of what it gives me, so it’s been helpful. It’s given me ideas on different topics that maybe I’m not an expert on.”

In California, school psychologist Brytnee Peacock has felt her day-to-day shifting toward more of a counseling role. “With high caseloads we get a little bit burnt out,” she says. “You’re looking at your computer screen thinking, ‘I need to create something for the student.’ But sometimes you’re just out of steam.” When Lenny was introduced at one of her team’s monthly meetings, Peacock had reservations. “I was thinking I don’t really want to work with AI; these are things that we are trained to do.” But as she familiarized herself with the platform, her feelings changed. “Instead of spending 16 hours creating group curriculum with my colleague, pulling from research, I’m doing what I was doing in 16 hours in an hour and a half.”

‘A HUMAN IN THE LOOP’

A number of factors prevent students from seeking the help they need—fear of judgment, shame, or a sense that asking for help won’t make a difference. For a teen or tween who might never walk into a counselor’s office, a chatbot can feel like a lifeline or even a friend. Unsupervised, vulnerable young people may try to navigate their deepest struggles with only an algorithm for guidance.

Entrepreneur Drew Barvir saw a critical gap: Most chatbots lacked real human oversight at the moment students needed it most.

When developing the Sonny chatbot, Barvir set his mind on what AI developers call the “human in the loop” model. Sonny is a “well-being companion,” available to more than 4,500 public middle and high school students in several districts for $20,000 to $30,000 per year, according to the Wall Street Journal. Unlike Lenny Learning, which is used by educators, students address their questions directly to Sonny—engaging in real-time, virtual conversations. Behind the Sonny persona is a team of trained human coaches assisted by AI working rotating shifts to respond to messages they receive from students within seconds. “What we’re doing is using AI to make our team of coaches more efficient, effective, personalizing the experience, and integrating within the ecosystem of the school districts,” Barvir told me.

Student users don’t interact with AI services directly, but the coaches have access to an AI “copilot” that assists with the administrative and analytical heavy lifting, like identifying what each student responds best to (problem solving, active listening, etc.), and sending schools high-level population insights, Barvir adds. The copilot also matches students to appropriate community resources should they require a referral to a mental health professional. After school and evenings from five to midnight are high use periods, but students have access to the chatbot 24 hours a day. When the service was made available at Berryville High School in Berryville, Arkansas, 175 students signed up for it. The service identified a student expressing thoughts of suicide at a high school in Marysville, Michigan.

Common topics range from issues with relationships and loneliness to general anxiety, school avoidance, and lack of motivation.

“I can become very obsessive about situations, and I know I can annoy my friends when I talk about a certain situation over and over,” 17-year-old Michelle told the Wall Street Journal. “I don’t feel like I’m annoying Sonny.” Immediacy and accessibility is part of the appeal, and danger, of some other AI chatbots on the market—positioned as confidants or even therapists. In September, the Federal Trade Commission announced it was investigating AI-powered chatbot companies like Character.AI and Replika to see how they “measure, test, and monitor potentially negative impacts of this technology on children and teens.” That’s likely in response to high-profile stories like that of the Raine family, whose 16-year-old son began seeking unsupervised emotional support from ChatGPT. He died by suicide after a long series of interactions with the artificial intelligence bot. “Teens are telling us, ‘I have questions that are easier to ask robots than people,’” Emily Weinstein, executive director of the Center for Digital Thriving, told KQED about the results of their recent adolescent survey.

Barvir’s service isn’t meant to replace mental health practitioners or human-to-human interaction: “There’s always going to be young people that need to sit down with someone face-to-face and talk through a challenge or see a therapist,” he says. “We want to help that model continue to exist while also reaching kids in real time and providing them with support.”

‘THIS IS JUST THE BEGINNING’

Time is a precious resource, and Lenny Learning claims to return a startling amount of it to teachers: As of late September 2025, staff in the Uncommon charter network had created 699 lessons with the chatbot’s assistance—saving over 2,000 hours, according to the platform’s calculations. “It’s not like new time just magically appears,” cofounder Bryce Bjork says. “Counselors have backlogs, teachers have other things to do.”

Inside some schools, Lenny’s presence can be felt throughout the entire school year. At a middle school in the Uncommon network, school social worker Joleen Shillingford used the platform to help her brainstorm ways to facilitate productive discussion during Mental Health Awareness Month at an all-boys school.

Meanwhile, at an Uncommon high school, school social worker Crystal Sullivan helps a student to rethink her disruptive behavior. “One of my students was getting into being disrespectful to her teachers and peers, getting sent out a lot,” she says. Sullivan began cocreating activities with Lenny to work on in their one-on-one sessions. “I started printing some of the lessons out for her about frustration tolerance and anger management. I give her stuff to go home with, and then she comes back and we discuss it. She’s been a little bit more calm now, but this is just the beginning.”

Amid a sea of plush toys and a furry Technicolor rug in school social worker Jasmin Mendez’s office, an elementary student is sitting in a small green chair, perusing different scenarios from laminated cards and role-playing how to handle them with kindness and respect. Mendez asks if the boy can give an example of when he’s been respectful at school. “I’ve never done anything respectful at school,” he responds, smiling coyly. She laughs: “Yes, you have! I think that maybe you’re not giving yourself enough credit.”

His face perks up. He remembers something: a time he was being kind by helping his teacher to collect laptops in his classroom, and respectful because he kept them closed so they wouldn’t break. “I love that,” Mendez exclaims.

He doesn’t know that Mendez used AI to cocreate the scenario cards or the lesson he’s engaging in. All he knows is that for the next 30 minutes, he’s in a safe space with someone—a real, flesh-and-blood human being—who has more time to listen and show him they care.

*A pseudonym has been used to protect the child’s identity.