8 Ways to Help Middle Schoolers Imagine Their Future Careers

Middle schoolers don’t have to pick a career yet—but research shows they’re already curious and eager to explore what’s possible.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Most schools don’t give students a chance to think about their futures until high school, but a recent article published by the Association of Middle Level Educators argues the optimal window actually opens as early as middle school—and too many schools are missing it.

In middle school, kids are open to “exploring and trying new things—and aren’t as affected by what their peers think,” AMLE writes. They also aren’t experiencing the “crunch time” effect of intense academic strain, college admissions stress, and heightened extracurricular expectations that high schoolers generally face.

By giving kids the opportunity to explore possible careers “without the heavy burden of expectation on their shoulders,” we can help students “determine not just what jobs they might want in the future, but who they are. What makes their eyes light up? What are they curious to try? What can they talk about for hours?”

The research says middle schoolers crave these opportunities: 85 percent are already thinking about future careers and 87 percent are interested in ways to match their skills and interests to potential careers, according to a 2022 report from American Student Assistance.

This makes sense when you consider what’s happening in adolescent brains: A 2024 study found that teens are innately wired for big-picture thinking, naturally seeking connections between their learning and broader questions of purpose, future goals, and cultural implications. It’s a finding that lead researcher Mary Helen Immordino-Yang says has “important implications for the design of middle and high schools,” highlighting the need to create learning experiences that honor even younger students’ developmental readiness for deep, sometimes challenging, future-oriented questions about their place in the world.

Here are eight activities that can help middle schoolers think more expansively about their futures—prompting them to question initial assumptions about what careers might fit their emerging interests and strengths, while also exploring possibilities they’ve never considered.

Stir Up Ideas: Hypothetical questions are an invitation for students to think outside of the box, creating distance between common “assumptions and limitations that can hinder career exploration,” writes Lucy Sattler, a career education professional. “They don’t need to ‘factor in’ anything other than what they’re interested in, and this is incredibly liberating.” Consider kicking off an advisory period or writing exercise with scenarios that encourage thinking beyond the present. For example, if you could build a career around something you're secretly good at, what would it be? Or, what career would feel like getting paid to be who you already are?

Look 'Behind the Scenes': High school English teacher Cathleen Beachboard helps students uncover unexpected career paths by digging deeper into areas that already spark their interest. “Jobs Behind the Scenes” (which can be used as a group brainstorm activity or a research project) asks students to identify the experiences they enjoy—like visiting a theme park or going to a sports game—and name all the behind-the-scenes jobs that make it possible. “For a concert, they might discover: sound engineer, stage designer, merchandise manager, lighting technician, tour planner,” she says. “It helps students understand that every big experience they love is powered by a wide variety of career roles, not just the ones in the spotlight.”

From Pie Charts to Purpose: Young students often limit their future thinking to areas where they currently excel, excluding fields where they could develop competence over time, notes Phyllis Fagell, a middle school counselor and author of the book Middle School Matters. She helps students break out of this by sharing stories of real-life figures who pivoted mid-career—such as Vera Wang, who went from figure skater to fashion designer—and using an engaging activity to help students put this philosophy into practice.

Give students two blank pie charts, then ask them to divide the first by how they currently spend their time and the second by what they wish their time allocation looked like. “The activity is about self-exploration and self-awareness,” Fagell explains, “learning to trust their instincts about the direction they might want their life to go in while shedding faulty pre-conceived notions about what they're supposed to do.”

She follows up with questions that connect time to career thinking:

- Looking at your "wish" pie chart, what activities take up the most time? What careers might build on those interests?

- Which slice represents something you're naturally good at AND enjoy doing?

- Are there any activities in your current chart that you excel at but don't actually like? What does that tell you?

Meet Future Me: “A lot of the time, teenagers feel like they’re not in control,” Beachboard says, so it can be powerful to remind them of areas they can start influencing today. Her “Future Goals Gala” is a 30-year class reunion (held 30 years early)—kids come dressed as the people they plan to become, complete with homemade props to prove it. Past students have brought in everything from cakes they made as aspiring Michelin chefs to their cure for cancer in a vial.

Before the event, students complete a guiding worksheet with questions like: What places do you really hope to visit? What kind of impact do you hope to have in your community in your field of study? As Beachboard meets each student’s “future self,” she notes students with overlapping interests who might work well together and small passions she can weave into upcoming lessons. “For a teacher who says, ‘This seems like a lot of extra work,’ it is, but it’s worth it,” she says. “This shows that you are invested not just in the student for their education, but in the person they’re going to become.”

Start With Strengths: Instead of starting with the potentially intimidating question “What do you want to be?”, this station rotation activity asks students to examine what they’re already capable of. Each station represents a different strength—from creative thinking and problem solving to leadership. Students complete quick challenges at each station by drawing a task card with scenarios like: You need to organize a school-wide event, or You have to solve a disagreement between two friends. Students then “match the scenario to one of their identified strengths and explain how they would use that strength to respond to the challenge,” Beachboard says.

After completing the station rotation, they can reflect on their top strengths and use a career-matching tool like My Next Move to explore jobs that align with their skills.

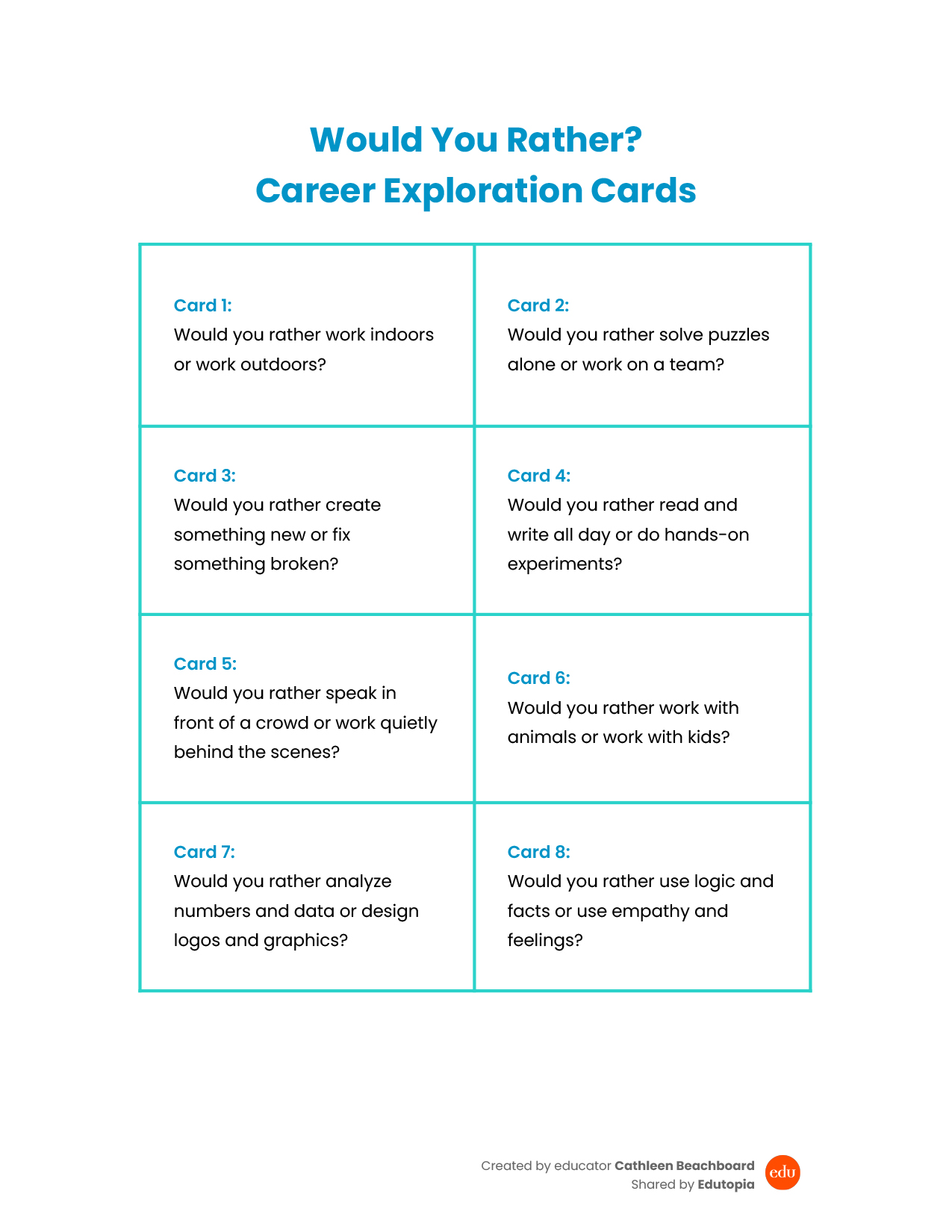

Turn Preferences Into Career Clues: A simple game of “Would you rather…” can help orient students a little more clearly toward what they might see themselves doing in the future. Beachboard asks all of her students to stand up and move to either side of the classroom based on their response to prompt cards. For example:

- Would you rather create something new or fix something broken?

- Would you rather have a job where you follow clear instructions or one where you figure things out on your own?

- Would you rather help people one-on-one or make a difference for a large group?

After the full set of 30 questions, they fill out a Google Form version of the activity and Beachboard uses AI to generate a personalized list of 20 careers that match their preferences. “From there, they choose a few careers to research more deeply—writing or presenting a ‘Day in the Life’ reflection about what someone in that field actually does,” she says. “It’s simple, scalable, and never fails to spark meaningful conversation.”

Educational consultant Toby Fischer takes a slightly different approach to help students envision their future selves. After listing five personal traits or goals—for example, “I love animals” or “I’m a great team player”—students feed them into an AI tool of their choosing with this prompt: “Based on the following traits, write a creative and funny prediction of who I will be in 10 years. Include my job, where I live, what a typical day looks like, and something surprising about my future self.”

Visit the Office (Virtually): Virtual field trips allow students a chance to experience a day in the life of careers they’re interested in. After researching salary, education prerequisites, and demands for various medical professions, teacher Brandi Burger’s anatomy and physiology students observed a knee-replacement surgery in real-time via video call and asked questions as the doctors performed the surgery. For some, it was a reminder that real-life medicine is “less bloody and more intricate than the dramatized television versions,” Burger says.

At the middle school level, this idea can be replicated with more age-appropriate virtual visits. For example, students could observe animal examinations at a veterinary clinic, routine cleanings at a dental office, or diagnostic procedures at an auto repair shop.

Hear From The Pros: Instead of simply reading about a career, career and technical education teacher Nancy Kuhn sends students straight to the source. Each year, her eighth graders conduct personal interviews with a professional in a field of interest—from architects to electrical engineers. Rather than giving out a set list of questions, task students with researching their interview subject and chosen field in order to create their own.

After the interviews, students can present what they’ve learned to their classmates with a slide deck or short video. To ensure variety, consider requiring that no two students choose the same career. Even if one student who’s interested in medicine interviews a phlebotomist, another could speak to an ultrasound technician, a paramedic, or a patient advocate.