29 High-Impact Formative Assessment Strategies

These versatile strategies—from brain dumps to speed sharing—help students track their own progress while informing your next instructional steps.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.In the midst of a packed class period, formative assessment can fall by the wayside. For new and even veteran teachers, it can be easy to overlook the wealth of “timely, evidence-based insights into learning” that regular low-stakes pulse checks can reveal, writes veteran Spanish teacher Maureen Magnan.

No matter your approach—from observation and cold calling to quick writes, exit tickets, and concept maps—formatively assessing students helps “measure the stickiness of teaching” so you can design or nimbly adjust your next steps in instruction, says instructional coach Kathy Collier. The exercise also benefits students, immediately revealing crucial information they’ve missed, determining mastery levels they should aim for, and pinpointing where they might be stuck.

Here are 29 formative assessment strategies that pack a punch—tested in real classrooms, varied in length and format, and designed to give students multiple (ungraded) ways to think about and demonstrate what they’ve learned.

Yes/No Chart: After students create a T-chart on a piece of paper, ask them to list what they do understand on the left side and what they don’t understand on the right. This can be done throughout the class period, with students filling out the chart as the lesson progresses or at the end. (Sourced from Terry Heick)

Misconception Check: Present a couple of common misunderstandings and challenge students to use what they learned in class that day to correct them. Alternatively, share a statement or solved equation and ask them to identify the mistakes. For example: Congress is part of the U.S. government’s executive branch. (Sourced from Laura Thomas)

Poker Chip Check: Each student receives four poker chips, which they keep on their desk. Green signals things are good. Yellow indicates they have a question. Red is a call for help because they’re completely lost. Blue means they’d like a one-on-one with you. At a glance, you can look out and get a feel for how the class is doing quickly, then adjust accordingly. (Sourced from Eric Osborne)

Help Me Plan: Divide students into small groups, asking each cluster to discuss how their learning went that day. Visit each group to gather their input: What do they think the class should review or clarify tomorrow, and where might the class go deeper? (Sourced from Mark Hansen)

Dos and Don’ts: On a sheet of paper, students each list three things to do and three things to avoid that are relevant to the lesson’s content. For example: With fractions, don’t forget to simplify your final answer. Do multiply straight across. (Sourced from Terry Heick)

Index Card Reflections: After a lesson, ask each student to write on an index card what surprised them, what they found interesting, and lingering questions. Students can write their names on them or answer anonymously. Collect the cards and review. If you have time, shuffle them and read some reflections out loud to encourage discussion. (Sourced from Barbara Erts Murray)

Word Cloud: Ask students to share three words that capture their key takeaways from the lesson. Enter their responses into a word cloud generator and have the class analyze common themes, as well as what’s missing. (Source: Meghan Mathis)

Jeopardy in Reverse: Provide an answer to the class—chlorophyll, for example. Next, have students each write a question that would lead them to that answer. For example, in a middle school science class, “What makes plants green and helps them make food?”

Similarly, prompt students to ask a question that provides you with context about their understanding. For example, in a high school English language arts classroom where you’re curious who did the reading, a student might ask, “In Chapter 4, Nick and Gatsby have lunch with Meyer Wolfsheim. What do Meyer’s cufflinks (made from human teeth) imply about his character?” (Sourced from Ann Sipe and Amy Goldman)

Assess Yourself: On the board, write three or four areas that you think the class needs to work on. Students come up to the board and write their names under the topic they feel they need the most support with. (Sourced from Laura Thomas)

Brain Dump: With a timer set for one minute, students write down as much as they can recall from the day’s lesson. Repeat this process for two minutes, then three. Have students compare the three dumps: What core ideas surfaced each time, and what gaps suggest areas for review. Or, alternatively, ask students to write three different summaries of their learning—one in 10–15 words, then 30–50 words, and lastly 75–100—then compare them with each other. (Sourced from Sophie Westermarck and David Wees)

Speed Sharing: Give students a problem or equation that will take around two to three minutes to answer. Students will work independently at first. When the time is up, have them find a partner to share their approach with, jotting down any new strategies or insights. Repeat the cycle with another question or two, then debrief altogether as a class. (Sourced from Joanie Hartnett)

Random Question Generator: Type up several closed and open-ended questions connected to the content students are learning. Print them out, cut them into strips, and collect them in a container. Periodically, ask one student to reach in and grab a question for the class to answer. For example: What can you tell me about functions? Or, what is the formula for the area of a circle? (Sourced from Beth Fulmer)

Here’s What You Missed: In pairs, students work to create a bulleted list of key takeaways to share with classmates who were absent that day. Or individually, ask students to record a 60-to-90-second voice memo explaining the lesson as if they were speaking directly to the student who missed it. Their peers may be encountering much of the information for the first time, so encourage them to be thorough. (Sourced from Paul Holimon and Cathleen Beachboard)

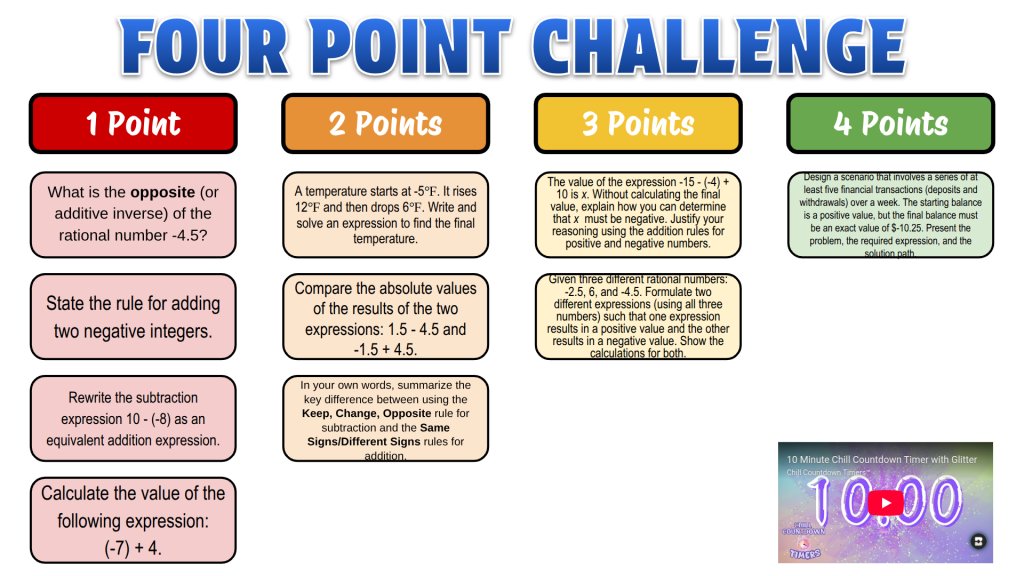

Four Point Challenge: Create four columns labeled 1–4 points, with each column containing questions at different difficulty levels (Depth of Knowledge 1 = 1 point, Depth of Knowledge 4 = 4 points). Students can choose any questions to answer as long as they earn a total of four points. For example, they can answer one higher-level question to earn all four points or answer four easier questions that are each worth one point. (Sourced from Kaleb Sauer)

Venn Diagrams: After drawing two overlapping circles on a sheet of paper, have each student compare a recent topic you’ve introduced on the left side of their diagram with something you taught previously on the right. Similarities are listed in the overlapping middle. For example, students can compare and contrast fractions and decimals. (Sourced from Meghan Mathis)

Pop Quiz Pulse Check (with a fun twist): Give students a quick, ungraded quiz of five questions or less. Review answers immediately after so they can see how they did and where they need more practice. Remind them this quiz is a tool for learning (not an evaluation or a grade). Collect the quizzes afterward for a deeper review. To keep the mood light, encourage early finishers—or everyone, if you add a few minutes at the end—to doodle on the back of the quiz. After reviewing the answers, allow a few students to share their doodles with the class. (Sourced from Rita Mullen)

Peer Reteaching: After students learn a new skill or concept, pair them up and ask them to reteach it to each other—for example, in a PE setting, after learning how to properly overhand-serve a volleyball. As they explain and demonstrate, circulate around the room and observe how clearly they’re able to recall. Do they capture the key points? What’s missing? (Sourced from Jermaine D)

Four Square: Students start by folding a paper into four equal squares. Assign four quick tasks, each corresponding with one square. For example, students can write one sentence using a vocabulary word in square one, jot a question they still have in square two, and draw a key concept in square three. Then they share the concept they’re most confident and clear about in square four. After they complete all four squares, collect the papers and review. (Sourced from Amy Carr)

Weekly Roundup: At the end of the week, ask students to volunteer (or you can cold-call) to build a collective list of what they’ve learned. Ask questions like these: What was challenging and why? What worked well for you and why? What was easiest to remember, and what helped make it stick? (Sourced from Dawn CB)

Checklist for Understanding: Create a checklist of important topics from a unit. As new topics are introduced, students check them off—self-assessing their comprehension level by writing one or two sentences explaining how they know they understand it or where they’re still struggling. Collect these checklists periodically to review. (Sourced from Rebecca Alber)

Human Bar Graph: Designate one side of the room as “I’m still lost” and the other side as “I could teach this.” Students position themselves along the spectrum based on their level of understanding, then discuss with nearby peers which concepts they feel confident about and what still confuses them. After these conversations, students can reposition themselves based on how their self-assessment has shifted. (Sourced from Cathleen Beachboard)

Tripwires: After learning a new topic, each student lists three things that might confuse or trip someone else up while learning the material. For each potential misunderstanding, they’ll share a sentence explaining their reasoning. (Sourced from Meghan Mathis)

Four Corners: Present students with a statement or question. Each of the four corners of your classroom will represent a different response or position (for example, “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” “Strongly Disagree,” and “Disagree”). Students walk to the corner that most clearly articulates their thinking, discussing why they chose this position with the others gathered in the same corner. (Sourced from The Teacher Toolkit)

Silent Partners: Students receive a card showing the same concept in various formats—for example, 1776, the Declaration of Independence, American colonies declared independence. Their goal is to find partners with matching information, but there’s a catch. They must find their matches without speaking. Any talking resets the game and forces everyone to start over again. (Sourced from Kathy-Ann St. Hill-St. Lawrence)

Give One, Get One: Set a timer and have students circulate through the room, pairing up with different classmates. In each pairing, they take turns: One shares an insight or takeaway from the lesson while the other writes it down, then the roles reverse. As students connect with more partners, their individual notes expand. Listen to the conversations and jump in as needed to ask a clarifying question or correct a misunderstanding. (Sourced from TeachThought)

What Stuck: On a large poster board, write: “What Stuck With You Today?” Close a lesson by having students write their main takeaways on sticky notes, then add them to the chart—clustering their ideas near related responses as the board fills up. (Sourced from Michele Wallace Oakley)

Transfer to New Contexts: Challenge students to apply today’s concepts to an entirely new, unrelated scenario. For example, how might they use the scientific method to strategize how to win against a rival soccer team in an upcoming game? (Sourced from Meghan Mathis)

Explain It to a Second Grader: On a sheet of paper or an index card, students explain a new concept they’ve learned, using the simplest terms possible. Since the hypothetical reader knows nothing about this topic, they’ll need to be thorough and clear. The goal: A younger student should be able to read this and understand. (Sourced from Todd Finley)

Muddiest Point: Thinking back on the day’s lesson, students identify where they lack clarity by answering the question, “What was most confusing to me about the material in class today?” Extend the activity by asking them to also identify their clearest point. (Sourced from Kimberly D. Tanner and Melanie Smith)