Good Lessons From a Bad Teacher

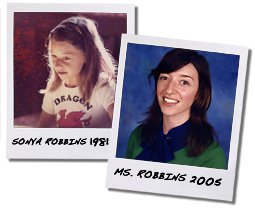

Teacher Sonya Robbins draws inspiration from her teen years, and remembers her worst teacher, so she can be a better one today.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Sonya Robbins has the kind of wincing clarity that comes from two decades worth of perspective. Back in middle school, she was a pill. She terrorized her eighth-grade teacher -- we'll call her Ms. Redding -- and Ms. Redding terrorized her right back. It got so tense that there had to be interventions.

Robbins was the kind of student that she, herself, has to struggle with today.

Now 33, Robbins beat a path from exasperating adolescent to, well, the opposite. She's a teacher, having joined the Brooklyn Charter School in 2002. She's developed a firm but loving rapport with her first graders, and, at some level, this carefully constructed relationship grew out of her own experiences as a student.

Lessons from a Bad Teacher

Sonya Robbins: Now that I've been a teacher, I think about the way I acted in school, and it makes me want to die. I have a lot more empathy for the teachers that I thought were being uptight at the time. I'm thinking about middle school. I was a nightmare. But I also had a nightmare of a teacher, Ms. Redding.

I went to an old-fashioned, all-girls school in San Francisco. For some reason, starting in seventh grade, I became incredibly uncooperative. The following year, I had this really hostile relationship with Ms. Redding. I felt completely persecuted by her. It got so bad, we'd have intervention conferences with my parents and the headmaster. She would come with notes -- typewritten notes -- about what I'd been doing in class.

I was too social. I chatted too much. I didn't focus. She really seemed to hate me. I remember borrowing my dad's Betamax video camera one day and interviewing everyone in my classes and all my teachers. When you get to the part of the tape with Ms. Redding, it's just a shot of her putting her hand up to the lens and saying, "Put that camera down." No sense of humor whatsoever.

It all came to a head one day when we were studying the Northern Lights. I had gone on vacation in Canada and seen them, and for some ridiculous reason, I felt this was really pertinent to share. I raised my hand, but she wouldn't call on me. I kept my hand up for 35 minutes, and she pretended not to see me. Eventually, the other kids started to raise their hands on my behalf. It really freaked me out. After class, I went to the pay phone and called home, crying. That inaugurated yet another of our conferences.

But now I see it from her side. As a teacher, you can get so irritated by your students. I understand what Ms. Redding was going through. I'm not sure I would call on a student like me, either -- someone who just wants the attention of telling the class she'd seen the Northern Lights. On the other hand, there might be a better way to handle it. A showdown with a child doesn't really work.

I think my own history in middle school is one of the reasons I gravitated toward teaching a younger age. The kids are less defiant in first grade -- less like I was!

Borrowing From the Good

There's another teacher from my past -- Mr. Olson, from second grade -- who I also think of these days. He made me feel smart. He'd publicly praise me for being a good speller, for example. I do that a lot as a teacher now. If you have a student that has a bit of talent in something, no matter what it is, find a way to celebrate it.

On that front, there's one exercise I do each year: I think of something positive about every student in my class. It's scary, because inevitably there are one or two kids for whom it's a struggle to find something to praise. But it's a great thing to do, and the little kids love it when you praise them out loud. After a while, you see them start to do it with one another. "You're really good at math," one will say to another. You create a culture of praise.

The challenge of being a good teacher is being able to balance your status as a clear authority figure with the need to connect with your students and relate to them. You have to remember why a kid might not be focused, why they want to make stupid comments, why they want to socialize. I make a conscious effort to remember that it's normal for kids to do all those things. And I remember that when they do, it's not a failing on my part or theirs.

It can get intense in the classroom, the place where you want students to do the right thing all the time. But I know from my own past that it's not always in the cards.