Do Your Final Projects Challenge and Motivate Students?

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.One summer, I spent weeks planning the following year's curriculum. By the time school started, I had rough plans for a culminating project: a living museum in which my seventh graders would dramatically present their learning about the fourteenth century bubonic plague in Europe. When I recall my own learning from that summer, I yearn for the classroom.

I am hoping that this story might inspire, might offer an example of an integrated way to teach and assess, and might invite our readers to share your own exhilarating final projects.

Luring Students to Learn

I usually start my instructional planning with an end product, project, or performance in mind. As we begin a unit and I inform students of our final project, they immediately get engaged and excited. Then I unpack the knowledge, skills, and understandings that students will need to have in order to be successful.

Middle and high school kids in particular often demand to know the purpose of doing an assignment or of learning some seemingly irrelevant skill. (There's always one kid who will ask, "Why do I have to learn this?") It is so much easier if I lure students into an instructional unit by dangling the final project in front of them. Then, they see the purpose of learning discrete skills, they see how the learning will be applied, they know that there will be an audience at the end, and they anticipate the fun.

Depth Over Breadth

At ASCEND, where I taught humanities to grades 6-8, we approached curriculum by prioritizing depth over breadth. Based on seventh grade California History and English Language Arts Standards, I designed a semester-long unit that explored how illness and death were dealt with in the Middle Ages. I focused on two case studies: ancient Mesoamerica (the Aztec and Maya) and Medieval Europe.

For three months, we studied the social, political, economic, religious, and medical systems of the European Middle Ages and how they were affected by the bubonic plague. Students were immediately captivated as they began reading texts that described the stinking pustules that erupted on the necks of knights and nuns, about the healers who applied leaches to the bodies of the diseased, and about the flagellants who attributed the plague to divine punishment and publically flayed themselves. They learned how the serfs who rose up in rebellion against their lords, and about the Jews and widowed women who were blamed for the illness and burned at the stake.

This was obviously juicy content and I exploited it to engage students in developing reading comprehension and word analysis skills, interpreting historical documents, analyzing medieval art, and writing a play based on what they learned.

The Museum Comes Alive

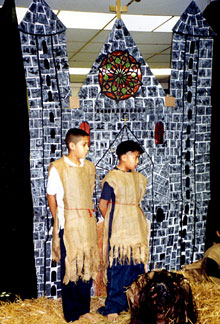

At ASCEND, we integrated the arts into all content areas. With the support of teachers from art, music, and drama, my classes and I planned a four-part dramatic performance. The cafeteria was divided into different areas, transformed into various settings in the Middle Ages. When spectators walked into one of the areas, the actors would suddenly come to life.

Working in teams, my 48 students (divided into two groups) collaborated on the scripts. Students selected the scene they wanted to write and perform, though first they took a written exam to demonstrate a deep understanding of the content matter. For example, those who wanted to be a serf had to explain the serf's role and position in medieval society, what their daily life was like, and how they thought and felt about the plague. They also had to reference the primary and secondary sources from which they gathered their evidence.

For several weeks, guided by myself and the other teachers, students memorized and rehearsed their lines, built the set, created the props, made costumes, and performed a musical composition. Everyone had to have at least one speaking part. Those with minor performance roles focused on the music and art.

In the end, there were four scenes: A serf's house where the men discussed the tragedy while a mother nursed a dying child; an apothecary's store, where members of the medical profession debated cures for the plague; a church, where monks considered causes of the illness while they worked on illuminated manuscripts and where a priest was indifferent to a parishioner's pleas for help; and finally, a central market square where traveling Franciscan monks declared their beliefs about the plague, flagellants whipped themselves and blamed the Jews, and an old woman went crazy as she ranted about "the end of the world."

The Learning

Perhaps most important was that while students were deeply engaged in the content and invested in creating the final product, they were also developing historical thinking skills, exploring Europe's history through a critical lens, applying their reading comprehension skills to difficult non-fiction and historical fiction, interpreting primary sources, writing in a number of genres, and developing their oral language abilities.

This living museum was performed eighteen times and visited by hundreds of children, parents, and community members. I had never seen my students as invested in their learning. But then again, there's nothing like the prospect of an authentic audience, plus a little blood and gore and injustice, to mobilize middle schoolers.

Several kids discovered a passion and talent for acting. Shy girls discovered that after some practice, they could deliver a compelling monologue loud enough for everyone to hear. Everyone learned that a project like this took a lot of time and was really hard and there were unexpected challenged. Yes, at times, tempers flared, but we also learned that such hard work is definitely worth it. And it was really, really fun.

How have you made final projects enriching and engaging for your students? We can't wait to hear!