Gone to the Dogs: Kids Connect with Canine Classmates

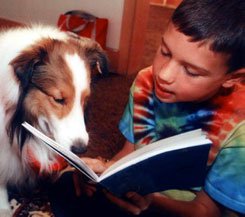

Reluctant readers thrive when they read with Rover.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Becky Bishop had a problem. As the community-minded owner of a dog-training facility in Woodinville, Washington, Bishop was in the habit of taking her trained therapy dogs to hospices to cheer up terminally ill patients. Over time, however, she found that the visits were depressing the dogs.

Then someone told her about a program just getting under way that pairs dogs and reading-challenged elementary school children; the dogs act as nonjudgmental listeners to help kids get over their fear of reading out loud.

"I started going to a library on Saturdays where the kids would come to read to dogs," Bishop says. "As soon as I brought my dogs around, they just lit up, and, of course, the kids did, too. All these parents began coming up to me and telling me how their kids had been such hesitant readers until they started in the dog program, and how enthusiastic they became. It ended up being such good therapy for me that I decided to start a nonprofit to spread the idea."

That was in 2000. Now, Reading with Rover, Bishop's organization, consists of some seventy-five dog-and-trainer teams that regularly go into libraries, bookstores, and schools in several Seattle-area districts to work with children who struggle with reading.

"The teams generally go to the schools on Thursdays, which statistically used to be the day with the lowest attendance; now it's the highest," says Bishop. "We've had hundreds, maybe thousands, of kids in the program, and the teachers tell us that being with the dogs changes their attitudes about reading immeasurably."

One teacher who latched onto the idea is Brian Daly, who has taught second grade at Rose Hill Elementary School, in Kirkland, for twenty years. Daly became so enamored of the program that he, his wife, Cathy, and their white Labrador, Silas, joined Reading with Rover as volunteers.

"We took Silas to our local Borders bookstore to check the program out," Daly says. "And, I tell you, that first night brought tears to our eyes. All these kids plopped down with the dogs, reading to them -- it was just magical. Such a simple idea, but so amazing."

Daly immediately began working to bring therapy dogs into his school, but his district had a rule against animals in the classroom. Nonetheless, with his principal, Joyce Teshima, who also owns a therapy dog, as an ally, Daly tried to figure out a way to get canines into class. "We finally discovered a loophole, which was to have the dogs certified by the International Delta Society, which screens animals and handlers," says Daly. "Once we convinced the district that the dog-and-handler teams were trained and regularly tested, they gave us the go-ahead."

The program, which started with second graders and targeted the lowest-level readers, was an instant success. The dogs, says Daly, became like "rock stars" to the kids, who collected and traded ink-pressed "paw-de-graphs" of their favorites. "They all have their special pals, but if a particular dog isn't available, they'll go read with another one rather than lose out. When we give reading homework, the parents say the kids whine about it, but they happily sit down and read with the dogs."

Betsy Brandon Leahy, a special education teacher at Woodmore Elementary School, in Woodinville, also got involved with Reading with Rover because of her dog, a black Lab puppy trained by Bishop. She and her dog began volunteering in the reading program at the nearby Bothell Regional Library five years ago, but when the program was shut down because of liability issues, she asked to bring the animals into her school. Her principal, Steve Wharton, whom Leahy describes as "definitely dog friendly," approved the proposal, and she says the experience has been a joy for all concerned.

"The volunteers come with the dogs once a week, and each child spends the whole trimester with the same dog," Leahy adds. "It's been amazing to watch these very shy kids, the ones that hate to read, become so enthusiastic. A real measure of success is when they start bringing their own books from home to read to 'my dog.' There was one little boy, kind of shy and socially not the coolest, who worked really hard on his reading, and his reward was to walk his dog back to class and introduce it to everybody. All of a sudden, he was the cool one, and all the cute girls were asking to meet his dog."

Reading-to-dogs programs are popping up all around the country, from northern California to North Carolina. In Salt Lake City, a group called Intermountain Therapy Animals has developed a training program known as Reading Education Assistance Dogs (READ). An affiliate of the International Delta Society, Intermountain Therapy Animals provides a home-study version of READ training materials and provides licensed READ workshop instructors in twenty-four states and in two Canadian provinces.

Through these instructors, READ provides on-site training to teams that attend regional workshops. More than 1,300 READ teams work in all but one state, as well as in three Canadian provinces and in England and Belgium.

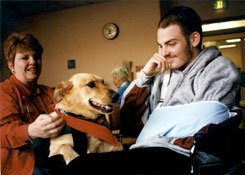

"Our volunteer therapy teams go into schools, libraries, after-school programs, detention centers, and hospitals where kids are in long-term wards," says Paula Dalby, READ's national coordinator. "We haven't done much in the way of studies, but the reading results are pretty evident, and the teachers and parents tell us that other intangibles such as self-esteem and personal hygiene improve when the kids have contact with the animals."

Part of the motivation to start READ, Dalby adds, was a series of studies conducted at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland demonstrating that proximity to pet animals lowers blood pressure and has a calming effect on humans. "That's not surprising if you love animals, as all of us who do this work obviously do," she says. "We can see the kids relaxing and forgetting their fears, because the dogs, unlike adults, or their peers, are attentive listeners who don't criticize them."

James Lynch, director of Baltimore's Life Care Health Clinic, is a noted author and medical researcher who conducted the studies. As a full-time faculty member at Johns Hopkins, the University of Maryland, and the University of Pennsylvania, he has spent some forty years studying the effects of loneliness on human health and well-being.

"We started out the study at Johns Hopkins looking at the effects of loneliness on heart patients, trying to determine what governs their length of survival," says Lynch, whose latest book is The Cry Unheard: New Insights into the Medical Consequences of Loneliness. "We looked at every variable, and the second leading predictor was whether the patient had a pet. Later, at the University of Maryland, we studied patients in coronary-care units and saw this phenomenon of remarkable changes in patients' heart rate and heart rhythms in response to simple touch from a dog."

This finding led Lynch and his team to examine the effect of pets on children. One study involved putting children alone in a quiet room to read while monitoring their blood pressure. "When they'd start to read, their blood pressure would instantly go up," says Lynch. "Then, when we simply put a dog in to wander around the room, the blood pressure quickly lowered. What the animal did was take the child's attention away from performance anxiety or other fears that make academic performance more difficult."

Though Lynch concedes that he knows of no studies that confirm the benefits of kids reading to animals, he says his intuition tells him that it works. "If you ask me to bet on it, I'd say it's ten to one that reading retention goes up when the dogs are involved. When your blood pressure rises to acute levels, it's hard to remember what you just read, but when you're calm, the obverse occurs. And kids know that pets don't judge you. If you yell at them, they lick you."

At Rose Hill Elementary School, Brian Daly knows that it works, too. He has seen it, and he has experienced it. "There are no hard data on the results, but when you see ability and attitudes and even attendance improving, you know something good is happening," he says. "With Microsoft so close at hand, we are in a very tech-oriented district, and this low tech idea of reading to dogs is so wonderfully refreshing and innovative. You've just got to love anything that encourages these kids to put away their video games for a while, and makes them eager to read."