The Heart of Learning: The Value of Cultivating Emotional Intelligence

Michael Pritchard is a healer, and a pioneer in the field of social-emotional learning, the often-neglected missing piece in a well-rounded education.

Your content has been saved!

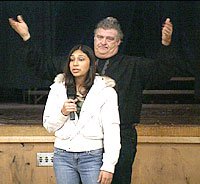

Go to My Saved Content.The guest speaker, dressed in black, paces slowly in front of the Castlemont High School auditorium stage, sizing up the audience. Tough crowd. Young men hunker down under sweatshirt hoods and baseball caps. Young women, overdressed for this sunny spring day, guard against the chilly atmosphere inside. They lean deep into their seats. No one is smiling.

"I'd like to take a moment of silence for all the young people we've lost on the streets," says the guest, a commanding baritone.

Most of these seniors simply stare back at him. And who can blame them? They are in shock. Like many high schools in America, this one in Oakland, California, has been a war zone. The daily weapons of choice are sharp words, dull stares, cutting laughter. If conflict escalates, as it did last year, when two students were wounded in front of this auditorium in a hail of drive-by bullets, everyone bears the pain of it.

"Thank you. And I'm sure the parents of those young people thank you," says the big man in black, Michael Pritchard. A friend of the former principal, he has come this day to help these students deal with the pain they live with every day -- whether they want him there or not.

Pritchard begins his presentation with barbs. "Ever hear something like this? 'You're ugly!'" he squeals suddenly, à la Porky Pig. "'You look like you fell out of an ugly tree and hit every limb on the way down.'" Giggles. "'Nice jacket. I used to have one like that. Then my dad got a job.'" Appreciative groans.

This is a man who knows how to work a crowd.

A Comedian with a Purpose

After winning the San Francisco International Comedy Competition in 1980, Pritchard toured nightclubs and appeared on TV shows with Robin Williams, Jay Leno, and Jerry Seinfeld. That year, he was also named California Probation Officer of the Year. At ease with young people, Pritchard has raised two sons and a daughter with his wife of 29 years, and has taken in, he estimates, "about a hundred or so" youths who have spent various periods of their lives growing up in his ever expanding extended family.

Pritchard's long-standing parenting gig has provided him with a wealth of comedic material. But the Castlemont crowd isn't buying his routine yet. And when he says, "We're talking to your hearts today," a voice in the back of the auditorium shouts, "Why?"

"Well, I'll tell you why I'm here," Pritchard shoots back. "Because I have two African-American youngsters that grew up with me and my family, and I love them and I'm worried about their lives. You don't know that. You don't know anything about me. I'm just a big, fat guy up here telling jokes. But, listen, we care about you."

Pritchard is a healer, and a pioneer in the field of social-emotional learning (SEL), the often-neglected missing piece in a well-rounded education. For the past two decades, he has been touring the country, talking and listening to students, teachers, and parents. He has written two books and produced a series of award-winning videos that focus on the critical issues of character and emotional intelligence for middle and high school students.

"What I try to teach kids is that we have to be more real about our emotions," explains Pritchard. "Shakespeare said, 'Always give sorrow words. Grief that does not speak whispers to the over-fraught heart and bids it to break.' I'm teaching kids that tears that do not flow will make other organs weep inside us. We get sick if we try to hold all that pain in. And then, the unaddressed grief turns to anger, and the anger to rage. And it has two directions -- out to the community, or inward toward the self, and self-destructiveness."

Into the Mainstream

For years, most mainstream educators have marginalized Pritchard and other SEL advocates. Now, though, their pleas for others who work with youths to "get real" about students' emotions are finally being heard. Late last year, the Illinois State Board of Education distributed the state's new Social and Emotional Learning Standards for K-12 students. Just as standards in language arts and math, for example, require students to achieve certain benchmarks, the SEL guidelines hold them accountable for proficiency in self-awareness, social awareness, and decision making.

For Maurice Elias, author of Raising Emotionally Intelligent Teenagers and Emotionally Intelligent Parenting, this is one school-reform effort that just might work. "When you look at the literature on education reform, it's replete with failure," says Elias. "We've been treating students as if they're not people -- as if they're somehow sponges, and not human beings that come in with their emotions in full play.

"I don't know of anybody that can learn in the absence of a positive relationship," he adds. "We learn from the people we care about. And yet we somehow pretend that in school, it doesn't matter. So, those who are actually concerned about academics should be concerned about social and emotional learning as well."

Numerous studies link emotional well-being to academic success, and stress to failure. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), based in Chicago, is conducting a meta-analysis of hundreds of such studies, and organization co-founder Daniel Goleman believes recent scientific discoveries confirm the link between emotional health and academic achievement. In the foreword to the 10th-anniversary edition of his groundbreaking book Emotional Intelligence, Goleman cites brain research detailing how areas controlling the emotions are located adjacent to the cerebral cortex, where cognitive processing occurs.

For Pritchard, teaching SEL is a no-brainer. "I say to the principals, 'No matter what we teach kids, love is more important than any knowledge we give them.' Because they can't become the gift that they're supposed to become if they're disconnected from their heart."

Making the Connection

At Castlemont, that heart connection is still tenuous. Teachers and administrators are working hard to change the culture here, splitting the large high school into small learning communities, and scheduling off-campus retreats where students and teachers can work through personal issues. But in the auditorium this day, the first students who volunteer to share their feelings in front of their peers are greeted with laughter and derision. But as brave souls continue to step up and sound off, the atmosphere in the room begins to shift.

"Dudes call girls bitches and hos," says Brian, twisting uncomfortably at the microphone. "But it opened my mind not to judge girls, because they're going through stuff. I've learned that one out of every three girls has been sexually assaulted. So that's all I'm saying. I just don't judge people."

Robyn is next. "It may look to you like I have nice clothes and I've got it going on. But when I get home, there ain't nothing in my refrigerator except ice cubes and water. People think that's funny? When you walk in those shoes, it ain't funny. And I got a seven-year-old brother. Little boys like to eat."

"You all might think my life is perfect," Jackie begins with a laugh. "I have both of my parents, sisters, and --" Her smile suddenly dissolves into sadness. "I'm talking to all you dudes out there who have some kind of addiction. My dad has an addiction with drugs and alcohol."

"What's it done to your heart?" Pritchard asks.

"It's done a lot -- to live with a father who will get his paycheck and go into a bar and not come back till three in the morning, or not even come back that night," says Jackie, sobbing. "Waiting up for him. It hurts, because I love him -- and I hate him at the same time for what he has done to my mom and my sisters."

The boys in the back who had been chatting during Pritchard's monologue fall silent.

A Different Vision

Poignant moments like these unlock something deep inside all who share them. They are potential turning points. But, in themselves, they are not enough to bring permanent change. "Creating an environment where kids feel comfortable, where they treat one another well, is not a one-shot deal," says Marilyn Clark, principal of Neil Cummins Elementary School, in Corte Madera, California, and a big fan of Pritchard's work. "It's wonderful to have someone like Michael Pritchard come in, but it's not a one-time lesson. Our responsibility is to reiterate that lesson, to keep it fresh, so that it isn't easily forgotten, so that it becomes the expectation. It's been my experience that it takes three to five years to change a school culture."

Like reading, writing and math, SEL skills can be acquired through focused lessons and reinforced by regular practice. The Resolving Conflict Creatively Program (RCCP), a research-based K-12 school initiative in social and emotional learning that focuses on conflict resolution, features classroom lessons in violence prevention and social and emotional skills such as empathy, cooperation, and appreciation of diversity. It also includes professional development for teachers, staff, and administrators, as well as parent training, and peer mediation.

The RCCP's national director, Linda Lantieri, says she sees the beginnings of "a whole new vision of education that says that educating the heart is as important as educating the mind."

Michael Pritchard moves that vision forward every day. He lives it now, resting a comforting hand on Jackie's shoulder, both of them fighting back tears as she comes to the end of her story. "My sister wanted to be a teacher, but now she's not, because my daddy didn't take care of her. But I'm gonna be somebody -- what my sister wanted to be. I'm gonna accomplish her dreams." She hands the mike back to Pritchard and walks off to applause and an embrace from a friend.

"That's it. Sorry we ran over," says the big man in black as he turns his back to the audience to wipe the sweat and tears from his face with a white towel. Even for a man who sees it every day, the power of emotion can be overwhelming. "Wow," he whispers. "Wow."